An academic dispute between Russian historian Alexei Miller and Finnish scholar Johannes Remy shows the opposing interpretations of Ukraine’s nineteenth-century national movement. In this article, Armen Tonoian analyzes their exchange, demonstrating how it engages with broader questions of deconstructing imperial narratives in Ukrainian history.

The article was developed during the course “Intellectual Debates in Modern Ukrainian History and Contemporary Public Sphere” at the Invisible University for Ukraine and prepared for publication in collaboration with Nadiia Chervinska (CEU). The article was supported by the Open Society University Network (OSUN) and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

In 2016, Finnish historian Johannes Remy published his monograph Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s. In the monograph, Remy tries to refute a central argument of the book The Ukrainian Question of the Russian Empire by renowned Russian Ukrainianist Alexei Miller, who claims that the weakness of government assimilation policies in the 1860s-1870s was one of the primary reasons for the success of the Ukrainian national project.1 For the first time since 2000, Miller’s conceptually and stylistically confident paradigm has been challenged.2

In historical scholarship, disagreements and debates are common. However, the intensity and personal nature of the exchange between Miller and Remy over the Ukrainian question in the nineteenth century particularly stands out. The debate consists of two articles, after which any apparent contact between the two scholars ceases. Miller initiated the exchange with a sharply critical review of Remy’s book in Scando-Slavica in 2017.3 In the subsequent journal issue, Remy provided his response to Miller’s review.4 The discussion extended beyond mere academic disagreement, raising fundamental questions about terminology, collective consciousness, and contemporary historiographical approaches to studying empires.

This article does not aim to deconstruct the position of either participant in the discussion. Although I examine the coherence, accuracy, and logic of the participants’ arguments, I aim to understand the broader aspects of this controversy. Since the onset of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014, Miller has consistently affirmed his pro-Russian stance in various situations,5 and the deconstruction of his intellectual position is neither novel nor necessary.

I argue that Miller’s critique of Remy’s book, while raising valid concerns about the theoretical framework and certain interpretations, ultimately aimed at discrediting Remy’s work rather than engaging in constructive scholarly dialogue. The debate demonstrates the crisis in studying the Ukrainian question in the Russian Empire, both in the post-Soviet and Western academia. In Remy’s case, it is evident that the nuances that researchers must consider leave little room for them to avoid criticism.

Throughout the paper, I seek to answer two questions. First, how did the debate unfold? To do this, I identify the most critical points of their debate, analyze how each scholar refuted the other, and compare these points with the perspectives of other reviewers of Remy’s book. Secondly, how does the Miller-Remy debate reflect the broader issues of the Ukrainian historical studies of the nineteenth century? I attempt to determine the implications for the terminology and identify challenges within imperial contexts of contemporary historiography.

Remy’s monograph attracted considerable attention from the scientific community. Several leading experts in their reviews praised the study (Serhiy Bilenky, Andriy Zayarnyuk, Ostap Sereda, Tomasz Hen-Konarski, Olga Andriewsky, Andrii Danylenko, Maxim Tarnawsky)6 or at least gave a moderate response (Volodymyr Kravchenko, Denys Shatalov, Stanislav Mohylnyi).7 The review of Tomasz Stryjek, who thinks that Remy failed to rethink Miller’s paradigm, is particularly valuable.8 However, I do not fully agree with his interpretation. I believe that refuting Miller’s concept was not Remy’s primary goal. Rather, Remy aimed to counter specific cases that support Miller’s paradigm. For instance, based on new archival documents, Remy argues that authorities were more repressive towards the Ukrainian national movement than Miller’s book suggested.9

Brothers or Enemies? Debate Core Arguments

In his monograph, Remy emphasizes some differences from Miller while adding that, metaphorically speaking, he stands on the shoulders of giants,9 referring among others to Miller’s monograph The Ukrainian Question of the Russian Empire. Remy also thanks Miller in the acknowledgments of the book for advice and help in searching archival materials in Moscow as well as for discussions at several conferences.10

Mutual assistance in academic circles does not (and should not) automatically imply a complimentary attitude in evaluating scholarly achievements. However, given the outlined context, Miller’s sharp critique of Remy’s monograph appears, at the very least, to be somewhat perplexing. Miller’s severe critique of Remy’s monograph stems from their common research interests. Both scholars seek to understand the specifics of imperial governance regarding the Ukrainian question.11 In both works, Fedir Savchenko’s Zaborona Ukrainstva (The Prohibition of Ukrainianness), published in 1930, serves as a foundational reference.12 Later historiography also compares Miller’s and Remy’s monographs, indicating their shared scholarly pursuits.13 Therefore, Miller might have reacted to this work as an attempt to deconstruct the value of his book. However, without access to personal correspondence and ego-documents, it is unlikely that we can determine the true reason behind this debate. Hence, it is worth focusing on how they debated rather than why they did so.

I identified seven key points of criticism that Miller raises against Remy’s monograph:

- Maksymovych: Miller disagrees with Remy’s characterization of Mykhailo Maksymovych as a “modern nationalist.”14

- Pirogov: Miller questions Remy’s conclusion that Nikolai Pirogov, a Superintendent of the Kyiv school district, did not see the Ukrainian movement as a threat. As Miller writes, it was Pirogov who initiated the process of banning the Latin alphabet for the “Little Russian dialect.”15

- Early independence: Miller doubts the validity of the claim that the Ukrainian activists in the 1850s–1860s had an early orientation towards independence, suggesting that Remy may have over-interpreted sources.14

- Valuev Circular: Miller opposes Remy over the nature of the Valuev Circular (1863), insisting that it was planned as a temporary measure rather than a permanent one.14

- Ems Ukase: Miller disagrees with Remy’s assertion that there was no opposition to the Ems Ukase (1876) within the central bureaucracy.15

- Theoretical Framework: Miller argues that conceptually, Remy’s work is poorly thought out, particularly in its reliance on the binary opposition of national identification processes and the neglect of “Little Russian” identity.15

- Source base: Miller criticizes the insufficient source base of the study, including the small number of archival documents.16

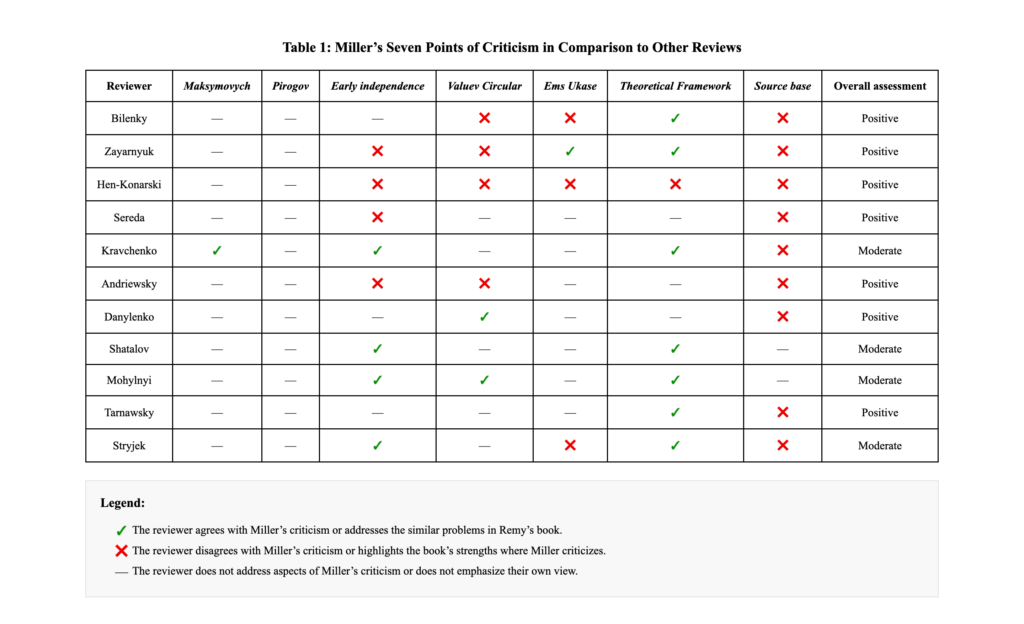

The analysis of Table 1 shows key aspects of how the scholarly community perceives Remy’s work. First, most reviewers (seven out of eleven) agree with Miller’s observation that the study’s theoretical framework is weak, expressing doubts about its validity.

Second, nine out of eleven reviewers agree that Remy’s archival research is thorough, especially in the analysis of the Valuev Circular and the Ems Ukase, refuting Miller’s criticism about the lack of sources. The statistical data support Remy’s stance on the severity of repressive measures during the 1860s–1870s, countering Miller’s claims. Third, the mixed assessments of the main thesis about the orientation towards Ukrainian independence within the 1850s–1860s national milieu (half of the reviewers supporting it and half opposing it) stem from an undeveloped theoretical framework which underscores the need for further research on the topic. Finally, Miller’s criticism of Remy’s points about Maksymovych and Pirogov finds no reflection among other reviewers, except for a few comments on the ambiguous portrayal of Maksymovych in the context of nationalism.

The reviews reveal a predominantly favorable response from the academic community: seven out of eleven reviews positively assess the study. Kravchenko and Stryjek offer balanced reviews, noting both the strengths and weaknesses of the book. In contrast, Shatalov and Mohylnyi, while recognizing the relevance and importance of the work, emphasize its shortcomings.

Miller’s initial observation is that Remy portrays Maksymovych as a modern nationalist in the famous Pogodin-Maksymovych controversy.17 Remy attempts to counter this assertion, arguing that Maksymovych was not precisely a modern nationalist. However, he also argues against labeling him as a pre-national thinker, emphasizing Maksymovych’s belief in the exclusive link between language and nationality. According to Remy, this connection precludes the existence of a nation with multiple languages, or a single language shared by diverse nations.18

Why is this question important overall? It relates to a broader understanding of how the Russian government viewed early proto-nationalist ideas until the end of Nicholas I’s reign. Bilenky considers both views erroneous: Miller argues that the Russian government failed to recognize the danger of the Ukrainian national movement and perceived it merely as pastoral nostalgia for nature, whereas Remy leans toward the opposite extreme by seeking a modern character in the representatives of Romanticism.19 According to Bilenky, the Russian government tended towards paranoia and was inclined to exaggerate the nationalist element in the ideology of Ukrainian Romantics, who were not yet modern “nationalists.”19 In my view, Miller’s assertion regarding Maksymovych’s “modernity” in Remy’s depiction is inaccurate. Remy portrays Maksymovych with more nuance, emphasizing that his views represented a transitional stage between pre-modern and modern perspectives. As Remy wrote in his book, “Such a view, incompatible with the idea of progress, shows Maksymovych as a rather conservative thinker in the context of the nineteenth century. However, the combination of language and nation with each other was an aspect of his thought that certainly belonged to the era of nationalism.”20

The second critical aspect raised by Miller concerns the interpretation of Nikolai Pirogov. Miller points out the contradiction between Pirogov’s positive attitude toward the Ukrainian movement, as described by Remy, and his initiative to ban the Latin alphabet for the Ukrainian script.21 This argument remains unanswered by both Remy and other reviewers. Remy explains the motives behind the ban of the Latin alphabet as an attempt to distance Ukrainian from Polish influence.22 A similar approach to addressing this issue can be found in Miller’s work.23 A careful reading of Remy’s work suggests that Miller may be correct in pointing out the insufficient argumentation regarding Pirogov’s “pro-Ukrainian” stance. Remy consistently emphasizes that as the Superintendent of the Kyiv school district, Pirogov promoted the development of Ukrainianness not as an end in itself but as a counterweight to Polish influences.24

In this context, the Ukrainian initiatives, such as the emergence of the journal Osnova in 1861, often found support within various circles of the Russian intelligentsia precisely as a counter weight to Polish influence.25 Although not claiming that Pirogov’s circumstances fit entirely within this framework, it is crucial to note that the argument that Pirogov lacked a negative attitude towards Ukrainian identity solely because he approved of anti-Polish actions by Ukrainianophiles requires further substantiation.

Miller’s third point centers on Remy’s assertion about the genesis of independence ideas in the Ukrainian milieu in the 1850s–1860s. Miller criticizes Remy for insufficient evidence, pointing to a limited number of cited sources:

“The fifth chapter describes the underground activities of Ukrainian activists at the beginning of the reign of Alexander II, in 1856–1864, primarily the Kyiv Hromada. Here, the author also cites four statements in favor of Ukrainian independence that he found, dating from 1858–1861, one in an anonymous article, two from private correspondence, and one toast. He considers this sufficient to conclude that the orientation toward Ukrainian independence, the emergence of which historians usually attribute to the last decade of the 19th century, is, in fact, 30–40 years older.”26

Remy does not directly respond to this criticism. Reviewers also show an equal split in their views on this conclusion, indicating the need to further refine this thesis. Despite Remy citing only four instances supporting Ukrainian independence, he claims that there were likely many more such cases.27 Even a Russian-language publication that generally supports Miller’s position acknowledges that Remy does not claim a fully formed ideology but rather individual expressions.28 In my view, Miller’s emphasis on the quantity of sources appears to be an attempt to discredit his opponent rather than scholarly criticism. Miller’s writing style suggests he is inclined towards ironic ridicule of this conclusion rather than a thorough analysis. Kravchenko, for instance, convincingly argues that the central issue in Remy’s conclusion on the early orientation towards independence is not about shifting the chronological framework or the adequacy of sources but rather the lack of clarity in the text regarding “what precisely changed, if anything changed at all.”29

The fourth and fifth observations concern repressive measures. In Miller’s review, the coverage of the Valuev Circular and the Ems Ukase is presented as Remy’s “factual errors.”30 Miller proceeds from the concept of the weakness and inconsistency of the imperial bureaucratic apparatus in implementing repressive measures against the Ukrainian language. He views the Valuev Circular as a temporary phenomenon31 and interprets the issuance of the Ems Ukase through the lens of conflicts and debates with oppositional ideas within the central bureaucracy.32

In response, Remy dedicates a significant portion of his article to a detailed examination of these issues. He argues that Miller interprets the sources without scrutiny, disregarding Valuev’s intention to permanently enforce restrictions on the Ukrainian language. Unlike Miller,33 Remy questions an entry in Petr Valuev’s diary, in which he mentions informing Mykola Kostomarov about the circular’s temporary status. Indeed, this source indicates the circular’s initially temporary nature. At the same time, Remy points out that by ceasing to consider lifting the restrictions, Valuev effectively turned a temporary measure into a long-term policy.34 Remy emphasizes that according to the circular, bureaucratic officials were supposed to prepare a second decision on this matter, and there were supporters of lifting restrictions against Ukrainian literature. However, Valuev halted the consideration of the entire issue, leaving the first decision in effect.35 Therefore, Remy does not deny the temporary nature of the circular at the initial stage but emphasizes that it was a common practice for temporary restrictions to be transformed into permanent ones.36 Remy’s analysis of the Valuev circular in his monograph, as confirmed by the analyzed reviews,37 is more nuanced compared to Miller’s.

Regarding the Ems Ukase, Remy disagrees with Miller in that the actions of the Minister of Internal Affairs Timashev and his deputy Lobanov-Rostovsky were in opposition to the implementation of the Ukase.34 While Miller attempts to demonstrate tension in Timashev’s and his deputy’s stance toward implementing the Ems Ukaz, he does not provide compelling evidence. He relies on assumptions: “The first attempt to ‘play back’ was made by Timashev immediately after receiving the final version of the Ems Ukaz. The documents do not clearly state what specific steps were taken. But it is clear that they were taken…”38 Remy acknowledges the possibility that Timashev sought to soften his stance toward members of the Kyiv Geographical Society. Yet, given that he was part of the special council that formulated the Ems Ukase and did not voice opposition to it, he can hardly be seen as its opponent.34 In recent studies published after Remy’s monograph, both views on the repressive measures of the 1860s–1870s are shown as competitive.39 But this is a difference of interpretation, not a “factual error,” as Miller notes. In general, it is unusual for a scholarly discussion to label interpretations of opponents as “factual errors” unless they are not related to clearly defined false claims.

Miller’s work is based on a meticulously constructed theoretical foundation, and the introductory section, where he presents his theoretical framework, comprises a fourth of the entire book.40 His criticism of Remy’s conceptual framework is based largely on Remy’s disregard for the Little Russian (without the quotes) identity, which in turn led, in Miller’s view, to the undeserved identification of Little Russians with Ukrainians and Great Russians with Russians.21 In particular, there is no confrontation between Ukrainian activists and holders of the Little Russian identity. Miller also uses the concept of “national indifference,” according to which nationalism is seen exclusively as a political strategy.21 In Miller’s opinion, Remy created a simplified binary model that poorly reflects the complexity of the ideas of the time.

In response, Remy notes that this critique is highly inaccurate, noting that the theme of complex variations of identity is central to his book.

As an example, he points out the strengthening of pro-Russian identity among some Ukrainian nationalist activists. He also reiterates his explanation of the usage of the terms “Russian,” “Little Russian,” and “Ukrainian.” Remy acknowledges the differences in meanings of these terms between the present day and the 19th century, as well as the plurality of these meanings at that time. His logic in constructing ethnonyms revolves around context. Remy emphasizes that he follows the variant (“Little Russian” or “Ukrainian”) found in the sources and prepares the reader for the possibility that the term “Russian” may appear with various meanings.41

Reviews of Remy’s book point out that his theoretical framework has problematic aspects. Bilenky notes that the work is relatively descriptive and does not depend on fashionable theories.42 Stryjek, comparing Remy’s monograph with Miller’s book, concludes that it does not undermine the paradigm of the latter.8 Kravchenko also touches on the terminological aspect: in his view, Remy is not a proponent of the term “Little Russian” and seeks euphemisms in inclusive (a combination of Ukrainian and Russian) and exclusive (Ukrainian) identities.43 As a specialist on Sloboda Ukraine, he argues that Remy’s definition of “Little Russian” is insufficiently comprehensive, thereby providing grounds for questioning certain conclusions and observations regarding the early stages and ideology of the Ukrainian national movement.43 Considering the described shortcomings, Miller’s criticism of the theoretical framework is valid. However, as Bilenky rightly notes, “Remy’s account is driven more by sources and facts and is devoid of sweeping generalizations.”36 It seems that Remy instrumentalizes ambiguous ethnonyms to achieve his rather clear and transparent goal: to describe the relations between the Ukrainian national movement and imperial policies towards it. Indeed, those reviews criticizing Remy for terminology that simplifies identities almost always acknowledge that he is honest with his readers about the issues his text raises and the answers it provides. As Zayarnyuk notes:

“Whether the triumph of the Ukrainian orientation was merely an outcome of a particular constellation of choices made by the governments involved with the ‘Ukrainian question,’ or whether there were more profound structural causes at work is a different matter, which Remy’s book does not explicitly engage. The book is careful to tackle only those questions to which well-documented answers could be given. It does the job extremely well and will be a must-read for anyone working on 19th-century Ukrainian history.”44

Miller’s final criticism concerns the source base of the study. Miller argues that Remy limited himself to only one fond of the Kyiv, Podillya, and Volyn Governor-General in the Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine in Kyiv (TSDIAK) for 1856–1865.45 Even without delving into the assessments of other reviewers and Remy’s responses, the reader can see that this statement is false. Apart from the TSDIAK, one can find references in the monograph to the Russian State Historical Archive (RGIA) in Saint Petersburg and the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) in Moscow.46 In his response, Remy provides more precise statistics about the unpublished sources: the work includes seventy-one documents from ten fonds across four archives (one in Ukraine and three in Russia).47

How sufficient is Remy’s source base? Most reviewers find this aspect of Remy’s work strong, if not decisive. Stryjek notes that Remy polemicizes Miller in specific cases and makes arguments only when he has “hard” evidence to support his view.48 Kravchenko observes that Remy’s in-depth research of archives and half-forgotten published documents is the most commendable aspect of the monograph, for which scholars will be grateful.49 Only two reviews specifically criticize this component of the work. Kravchenko notes that sometimes Remy positions some sources as newly discovered, although they have long existed in scientific circulation.43 Sereda convincingly demonstrates Remy’s source-related mistake in trying to establish cooperation between the Polish National Government and the Kyiv Hromada.50 Yet, both researchers assess the source component as a definite strength of Remy’s monograph.

Miller’s criticism of Remy’s book source base appears to frustrate Remy the most, as evident from the quote on the Academia.edu page, which Remy removed from the text of his response to Miller at the request of Scando-Slavica editorial board:

“Professor Miller is definitely right in that more archival documents would have improved my book. However, I find it not without interest to mention that in his The Ukrainian Question, Miller does not use any documents from the Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine, or any other Ukrainian archive. The archival base of his book is limited to the archives which are located in Russia. When I tell this, my intention is not to belittle the importance of Alexei Miller’s book which has solid archival base. Rather, I defend myself against his implicit claim that my book is not needed because it does not present sufficient new material or interpretation.”51

Remy refers to the original first edition of Miller’s book, which did not include sources from Ukrainian archives.52 The second edition of the book, published in Kyiv in 2013, apart from selected articles by Miller on Ukrainian studies over those 13 years, also included Ukrainian archival sources.53 Miller’s assertion about the insufficiency of the archival base, even when attempting to decipher his emphasis on Ukrainian archival geography, is inappropriate and, as Remy correctly notes, casts a negative impression on what is a strong aspect of the book, as seen in the reviews. Without reading the book, analyzing the context, and getting familiar with Remy’s responses, one might erroneously assume from Miller’s review that Remy uses only one fond from the Kyiv archive throughout the book. At the same time, Miller highlights that a significant strength of Remy’s book lies in its thorough exploration of censorship history,26 which is somewhat disconnected from the overall critical narrative of his review.

Many reviewers have criticized the title’s opening phrase: Brothers or Enemies. Miller underscores the binary nature of identities reflected in the title, which inadequately represents Ukrainian-Russian relations in both the nineteenth century and the present.45 Shatalov highlights the inappropriateness of the metaphor, which fails to accurately convey the essence of the book,54 while Tarnawsky notes that the publisher could have recommended a better title.55

Indeed, the title lacks effectiveness. Remy describes it as provocative,56 but it is also limiting. The title offers only two possible options for the development of Ukrainian-Russian relations: integrative (brothers) or antagonistic (enemies). This provided critics with additional grounds to assert the binary opposition of these relationships in the book. However, it is surprising that none of the reviewers mention Remy’s explanation of the title, which he provides in the monograph. According to this explanation, the original title included a question mark—Brothers or Enemies?—but due to technical complications with the book’s marketing, they decided to remove it.57 The question mark would have redeemed the title, preventing it from being declarative.

A detailed analysis of each of Miller’s seven remarks leads to the conclusion that, despite rational criticism of conceptual aspects of the work, his primary goal was to discredit Remy’s monograph. This is evident in his selective use of facts, emotionally charged language, and emphasis on weaknesses in places where the work is strong.

On the other hand, Remy neglects to address some of the critical comments from his opponent and instead overly fixates on the discrepancies between their perspectives, even in areas that Miller does not address in his review. As a result, Remy remains silent on the insufficient substantiation of Pirogov’s allegiance to the Ukrainianophile movement, as he states in the conclusion of his work. At the same time, his overall response appears more logical, well-argued, and directly addresses the critical comments.

The Challenges in Nineteenth-Century Historiography: Insights from the Miller-Remy Debate

On his Academia.edu page, commenting on the post of his response to Miller, Remy wrote that “Disagreements over Russian imperial policy on the Ukrainian question in the nineteenth century are not the main point of our controversy.”58 In my opinion, this debate raises several paradigmatic questions about how modern historiography comprehends the events of the nineteenth century. Ultimately, without some conceptual divergences, this discussion would likely not have taken place.

The Miller-Remy discussion touches on three key problem areas of both post-Soviet and Western contemporary nineteenth-century historiography: terminology, group identity, and imperial modeling. Although the challenges of studying this period extend beyond these three areas, they are particularly important for studies of the Ukrainian question in the nineteenth-century Russian Empire. These three categories are inherently interconnected, as terminology is a direct consequence of the conceptual approach that has been taken in the study of empire. At the same time, group identity and a sense of belonging emerged as a potential counterweight to imperial unification.

Terminology. Koselleck posits that language is a slowly evolving structure,59 which implies that all distinctive events expressed in this language occur within this structure. Consequently, researchers must first determine the linguistic forms and concepts that existed in their period of study and then develop an appropriate vocabulary to represent these linguistic nuances in the present context. Contemporary research on the nineteenth-century Ukrainian question often uses speculative constructions. In some instances, such interpretations frequently constitute a significant portion of the book, as in Miller’s case. Instead, Remy’s introduction serves solely as a tool for the reader, explaining what to expect in certain chapters, what the focus of the book is, and how to read particular statements. The two approaches address the issue of imperial orthography and language, as well as the various meanings of words.

True, almost all contemporary books in various languages encounter difficulties and criticism in this regard.60 For example, Shatalov notes that the modernization of historical terminology is a common problem in contemporary historical research but goes further and says that even the transcription of a name or surname can have conceptual or political overtones.61 He cites the example of Panteleimon Kulish, whose surname in the neutral form in the imperial era was written with an “ѣ” (Kulѣsh).62 The choice of the Ukrainian or Russian version may implicitly indicate a certain authorial position. The policy of de-Russification in Ukraine additionally intensified the focus on the selection of transcriptions.63 In the case of non-Ukrainian-speaking researchers, this problem is even more pressing. For example, the choice between Kyiv and Kiev is quite ambiguous. Remy prefers Ukrainian transcription,64 while Hillis and Miller prefer Russian.65 At the same time, Remy uses Ukrainian transcription for cities (Kyiv, Kyivan Rus’) but the Russian transcription for the Dnipro River (Dnieper).66 As for the surnames, in some cases, he indicates both Russian and Ukrainian transcriptions. Accordingly, in this inconsistency, one can notice manifestations of how contemporary language, one way or another, leaves its imprint on the depiction of the past.

However, the most pressing concerns pertain to terms that were fluid and ambiguous in the nineteenth century, primarily ethnonyms and spatial markers that refer to the symbolic geography of various competing projects. Miller dedicates a significant portion of his introduction to the analysis of the ideas of Lysiak-Rudnytsky and Omelian Prytsiak on the legitimacy of using the terms Ukraine and Ukrainians to describe historical periods when these concepts had a different connotation or territorial scope.67 Miller believes that the term Ukrainian should exclusively apply to those individuals who advocated for the development of the Ukrainian nation, a concept that is implemented to some extent today.68 Regarding individuals loyal to the empire, he proposes using the term “Little Russian,” as their aspirations were contrary to the Ukrainian project.68 At the same time, this division can also undergo critical analysis. Quentin Skinner wrote that the development of doctrines is tempting, but in reality, people’s ideas are inconsistent, contradictory, and variable.69 For instance, a segment of the Black-Hundred movement in the early twentieth century, notably the Kyiv Club of Russian Nationalists, aimed to contrast the term Ukrainian, which they viewed as separatist, with Little Russian, which they regarded positively. However, these terms were often used interchangeably in the Black Hundreds and monarchist agitation. Little Russian could denote opposition to imperial Ukrainian separatism, whereas Ukrainian might refer to those loyal to the Romanovs.70 This situation demonstrates the ambivalent nature of identification vocabulary even within the same organization.

Therefore, achieving a complete adaptation of analytical language in terms of neutrality, clarity in depicting identities, and logical understanding of these terms among research actors is currently unattainable. This challenge arises from intricate linguistic trajectories and the ongoing issue of defining “identity” and imperial studies in contemporary scholarship.

Identity. It is common for reviewers to use the issue of identity or the manifestation of a particular group identification to negatively portray certain aspects of historiography. In his review, Miller emphasizes the binary oppositions in Remy’s monograph that do not fully capture the complexity of identities in the 1840s and 1870s. Theodore Weeks expresses similar criticism of Miller and Dolbilov’s book, calling The Western Periphepies of the Russian Empire a Russian narrative. In his opinion, it focuses on imperial politics and Russian identity while ignoring the subjectivity of other identities in a multinational empire.71

Similarly, Remy also devotes considerable attention to criticizing the identity component of Ricarda Vulpius’ work.72 In this review, Remy discusses Vulpius’ attempts to avoid the dangers researchers of the Russian Empire face: “She tries to steer clear of both one-sided extremes, where exclusive attention is given either to the government’s viewpoint or the viewpoint of the studied nation.”73 In conclusion, Remy notes that a shortcoming of Vulpius’s work is a certain bias in prioritizing the Ukrainianophile discourse over the all-Russian perspective.74 Essentially, he critiques her for what Miller would later criticize him for.

Researchers are constantly dissatisfied with the coverage of identities in historical works about the nineteenth century. The main reason for this is that focusing on a particular national group almost always obscures its other potential identities that had not developed at the time. Ignoring the diversity of identities, which creates a certain incompleteness in historical reality, is almost always a deliberate move. Recent theoretical developments, including the concept of Multifrontier, proposed as a framework after the onset of Russian full-scale invasion in 2022 by a group of Ukrainian historians, potentially might offer a new toolkit to represent the polyethnic and transnational reality.75

Another problem is that the term “identity” is overused. The impetus for the rejection of this term was the 2000 article “Beyond Identity” by Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, in which the authors propose terms that are better suited to analyze collective consciousness, such as “identification” (as an active verb emphasizing dynamic processes), “commonality,” “connectedness,” “groupness,” and several other conceptual approaches that move beyond static notions of “identity.”76 John Joseph’s view of the human capacity to rapidly construct identities aligns with this perspective. He posits that we construct identities through purely linguistic interactions with individuals or sources. Joseph notes that even in poststructuralist studies, there is a tendency to define language in national movements as a primordial component. However, in his opinion, it is also a cultural construct.77

Problems of group identity and nationalism require researchers to create their own conceptual frameworks from fragments of different scientific approaches and theories, which greatly individualizes the final result and complicates the discussion. We can see this in the cases of Miller, Remy, and Vulpius, as each has faced criticism for portraying collective identities in their works.

Imperial models. In contemporary historiography, one can see a certain rehabilitation of the empire in scholarly studies or an “imperial turn.” Sereda emphasizes that the empires of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were inclusive, and only with the process of modernization and social mobility did the unification of space under a single canvas begin, which gives rise to alternative projects of group identity.78 This perspective also resonates with other studies, where scholars view early modern empires as contrasting with contemporary nation-states that were imperialized during the twentieth century. The idea that the empire must necessarily collapse ceases to be relevant.79 Eventually, the idea of a new imperial history emerges, which aims to combine the concepts of empire and nation as categories of analysis and not to comprehend them exclusively antagonistically.80

On the other hand, Hen-Konarski, in his review of Remy’s monograph, notes that “the English-speaking reader will finally have the opportunity to read the history of the formation of the nineteenth-century Ukrainian nation, not devoid of flesh and blood and not overburdened with imperial rhetoric,” clearly referring to Miller’s book.81 Similarly, Mark von Hagen characterizes Miller’s view as imperial with rather negative connotation.82 Finally, Remy himself is convinced that Miller holds a Russian imperial worldview.83 However, there is a difference between criticizing the imperial worldview, the imperial perspective on history, and the rehabilitation of empire as an analytical category.

Hen-Konarski, Remy, and Hagen consider Miller an imperialist because he looks at the Ukrainian question from the perspective of the center and does not subjectify the Ukrainian movement. His vision is oppositional (Miller writes alternative)84 to nation-centered historiographies that look from the opposite point of view. While the state as an institution often takes center stage in studies of the “imperial turn,”85 Miller is unlikely to be classified among the cohort of specialists in this model of imperial study. He was absent from discussions in the leading Russian-American journal Ab Imperio regarding the “new imperial history,” and the book Zapadnye okrainy Rossiyskoy imperii (Western Peripheries of the Russian Empire), where he was a co-editor, was cited by proponents of this approach as a negative example.86 Andriy Portnov pointed out that Miller’s neutrality is more stylistic than factual, as his constructivism tends to be selective.87 Moreover, Portnov notes that some pseudoscientific works by notorious Russian authors were based on Miller’s book. At the same time, Miller’s conclusions, for example, regarding the Russification policy of the Russian Empire since 1863, align with contemporary approaches of the “imperial turn” scholars. Like Miller, they state that Russification was chaotic, poorly planned, and did not aim for genuine cultural transformation in the regions where it was implemented.88 However, the difference lies in that Miller viewed the repressive measures of imperial authority exclusively through the prism of the All-Russian national project.

The question of innovation in imperial studies is most clearly traced in how the author manages the diversity of the empire rather than simply seeking to rehabilitate it in any way. The “imperial turn” requires the researcher to cover a wider range of issues and consider the synchrony of a particular field of study, not just the diachrony. Kravchenko points out that since the publication of Andreas Kappeler’s book,89 the Russian Empire has been perceived as a multiethnic state of various nations and cultures.90 In this context, Remy’s monograph is, at least speculatively, closer to the “imperial turn,” because it analyzes both the Ukrainian movement and imperial policy toward it.

Overall, these challenges underscore the need for ongoing critical reflection and methodological innovation in historical research. As Kravchenko notes, “…Ukrainian history presents a daunting challenge to any specialist in the field.”91 Indeed, the Ukrainian question serves as a microcosm of these broader issues, demonstrating the complexities of studying identity, terminology, and imperial dynamics in the nineteenth century. Even though it is improbable that these complications will be resolved soon, this does not diminish the importance of addressing them.

Bibliography

Aitov, Spartak. “Ukrainska istoriohrafiia ta zhurnal ‘Osnova’ v konteksti kulturno-natsionalnoho vidrodzhennia Ukrainy” [Ukrainian Historiography and the Journal Osnova in the Context of the Cultural and National Revival of Ukraine]. Dys. kand. ist. nauk, Dnipropetrovskyi natsionalnyi universytet, 2001.

Andriewsky, Olga. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Slavic Review 77, no. 1 (2018): 227–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2018.29.

Bertelsen, Olga. “Russian Front Organizations and Western Academia.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 36, no. 4 (2023): 1184–1209. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2022.2147807.

Bilenky, Serhiy. Laboratory of Modernity. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780228018582.

Bilenky, Serhiy. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 6, no. 1 (2019): 197–200. https://doi.org/10.21226/ewjus487.

Brubaker, Rogers, and Frederick Cooper. “Beyond ‘Identity.’” Theory and Society 29, no. 1 (2000): 1–47.

Danylenko, Andrii. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Slavonic and East European Review 95, no. 3 (2017): 568–70. https://doi.org/10.1353/see.2017.0034.

David-Fox, Michael and Peter Holquist and Alexander M. Martin, “The Imperial Turn,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 7, no. 4 (2006): 705–12. https://doi.org/10.1353/kri.2006.0049.

Fedevych, Klymentiy K. “Otvet Retsententam [Response to Reviewers],” Ab Imperio, no. 2 (2018): 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0037.

Fedoruk, Oles. “‘Otvet “Boyanu”–Stebelskomu na “Pysmo do Kulisha” (Pysmo k redaktoru “Pravdy”)’: Pytannia avtorstva [‘Response to ‘Boyan’–Stebelsky on ‘Letter to Kulish’ (Letter to the Editor of “Pravda”)’: Question of Authorship],” Literatura ta kultura Polissia 15 (2001): 3–17.

Fedoruk, Oles. “Z pruvodu odniiei dyskusiinoi atrybutsii [Regarding one debated authorship].” Slovo i Chas, no. 3 (2009): 109.

Gaukhman, Mykhaylo. “Mnozhestvennaya Identichnost Kak Issledovatelskaya Problema [Multiple Identity as a Research Problem].” Ab Imperio, no. 2 (2018): 213–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0035.

Gaukhman, Mykhaylo. “V Poiskakh Novoy Istorii: Istoriohraficheskie Diskussii Nachala XXI v. o Metanarrative Istoriyi Ukrainy [In Search of a New History: Historiographical Discussions at the Beginning of the 21st Century on the Metanarrative of Ukrainian History].” Ab Imperio, no. 3 (2022): 27–68. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2022.0060.

Gaukhman, Mykhaylo. Review of Children of Rus’: Right-Bank Ukraine and the Invention of a Russian Nation. By Faith Hillis. Ab Imperio, no. 3 (2017): 269–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2017.0067.

Gerasimov, Illia and Marina Mogilner and Alexandr Semenov, eds. Mify i Zabluzhdennia v Izuchenii Imperii i Natsionalizma [Myths and Misconceptions in the Study of Empire and Nationalism]. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2010.

Gnatiuk, Oleksiy and Anatoliy Melnychuk. “Housing Names to Suit Every Taste: Neoliberal Place-Making and Toponymic Commodification in Kyiv, Ukraine.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 65, no. 1 (2024): 34–63.

Gnatiuk, Oleksiy and Sergei Basik. “Performing Geopolitics of Toponymic Solidarity: The Case of Ukraine.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography 77, no. 2 (2023): 63–77.

Hen-Konarski, Tomasz. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Krytyka, no. 3–4 (2017): 233–34.

Hillis, Faith. Children of Rus’: Right-Bank Ukraine and the Invention of a Russian Nation. Cornell University Press, 2013.

Hrytsak, Yaroslav. “Mark von Hagen, ‘A Conscious Ukrainianist.’” Ab Imperio, no. 3 (2019): 233–242.

Joseph, John. Language and Identity: National, Ethnic, Religious, (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2004).

Koselleck, Reinhart. Chasovi Plasty. Doslidzhennia z Teorii Istorii [Temporal Layers. Research in the Theory of History]. Kyiv: Duh i Litera, 2006.

Kotenko, Anton. “Imagining Modern Ukraїnica.” Ab Imperio 1 (2015): 519–26.

Kravchenko, Volodymyr. “Putting One and One Together? ‘Ukraine,’ ‘Malorossiia,’ and ‘Russia.’” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 20, no. 4 (2019): 823–40. https://doi.org/10.1353/kri.2019.0062.

Mikhail, Alan, and Christine M. Philliou. “The Ottoman Empire and the Imperial Turn.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 54, no. 4 (2012): 721–45;

Miller, Alexei. “Ukrainskiy Vopros” v Politike Vlastey i Russkom Obshchestvennom Mnenii (Vtoraya Polovina XIX v.) [“The Ukrainian Question” in the Policy of the Authorities and Russian Public Opinion (Second Half of the 19th Century]. Saint Petersburg: Aleteyya 2000).

Miller, Alexei. “O serii ‘Okrainy Rossiyskoy Imperii’ i ob otklikakh Teda Viksa i Aleksandra Smolenchuka na knigu ‘Zapadnye Okrainy…,’ [On the Series ‘Peripheries of the Russian Empire’ and Responses by Ted Weeks and Alexander Smolenchuk to the Book ‘Western Peripheries…,].” Ab Imperio, no. 4 (2008): 358–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2008.0063.

Miller, Alexei. The Ukrainian Question: The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century. Budapest–New York: CEU Press, 2003.

Miller, Alexei. Ukrainskiy vopros Rossiyskoy imperii [The Ukrainian Question of the Russian Empire], (Kyiv: Laurus, 2013).

Miller, Alexei. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Scando-Slavica 63, no. 2 (2017): 231–34.

Mohylnyi, Stanislav. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Ab Imperio, no. 1 (2018): 316–23. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0011.

Portnov, Andrii. Istoriyi dlya domashn’oho vzhytku: Eseї pro Pols’ko-Rosiys’ko-Ukrayins’kyi trykutnyk pam’Yatі [Histories for Home Use: Essays on the Polish-Russian-Ukrainian Triangle of Memory]. Kyiv: Krytyka, 2013.

Remy, Johannes. “But That Is Not What I Wrote: Response to Alexey Miller’s Review of My Brothers or Enemies.” Scando-Slavica 64, no. 1 (2018): 112–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00806765.2018.1446864.

Remy, Johannes. Academia.edu, June 21, 2024, https://www.academia.edu/36262877/But_that_is_not_what_I_wrote_Response_to_Alexey_Millers_review_of_my_Brothers_or_Enemies.

Remy, Johannes. Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

Remy, Johannes. Review of Nationalisierung Der Religion: Russifizierungspolitik Und Ukrainische Nationsbildung, 1860–1920. By Ricarda Vulpius. Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 9, no. 4 (2008): 977–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/kri.0.0036.

Savino, Giovanni. “Europeanism or Nationalism? On Nation-Building in Europe and Ukraine.” Russia in Global Affairs 2018 (2): 94–105.

Sereda, Ostap. “‘Dity Rusi’: ‘Braty Chi Vorohy?’ Diskusiya Shchodo Ukrayins’koho Natsional’noho Rukhu Seredyny XIX Stolittia v Suchasniy Anhlomovniy Istoriohrafii [‘Children of Rus’: ‘Brothers or Enemies?’ Discussion on the Ukrainian National Movement of the Mid-19th Century in Contemporary English-Language Historiography].” Naukovi Zapysky UKU, no. 3 (2019): 293–300.

Shatalov, Denys “Brat’ya Ili Chinovniki? [Brothers or Officials?],” Ab Imperio, no. 1 (2018): 324–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0012.

Skinner, Quentin. “Meaning and Understanding in the History of Ideas.” History and Theory 8, no. 1 (1969): 3–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504188.

Staliunas, Darius. Polsha Ili Rus? Lytva v Sostave Rossiyskoy Imperii [Poland or Rus’? Lithuania as Part of the Russian Empire]. Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 2022.

Stryjek, Tomasz. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Acta Poloniae Historica, no. 115 (2017): 314–23.

Tarnawsky, Maxim. Review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s. By Johannes Remy. Canadian Slavonic Papers 60, no. 3–4 (October 2, 2018): 616–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2018.1480696.

Tolochko, Alexei. Kievskaya Rus’ i Malorossia v XIX veke [Kyivan Rus’ and Little Russia in the nineteenth century]. Kyiv: Laurus, 2021.

UkeTube. “Brothers or Enemies: Ukrainian National Movement & Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, Johannes Remy.” YouTube, 15 December 2016. Video, 45:13. June 21, 2024. https://youtu.be/-1uQVrHorOk?si=tnk2zWXTymAhVboU.

Volodymyr Masliychuk, Volodymyr. Review of Imperski Identychnosti v Ukrayinskiy Istoriyi XVIII – Pershoi Polovyni XIX St. [Imperial Identities in Ukrainian History from the 18th to the First Half of the 19th Century]. By Vadym Adadurov and Volodymyr Sklokin. Ab Imperio, no. 4 (2020): 254–261.

Weeks, Theodore. “The Challenges of Writing a Multi-National History of the Russian Empire.” Ab Imperio 2008, no. 4 (2008): 365–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2008.0085.Zayarnyuk, Andriy. Review of Brothers Or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s by Johannes Remy. Reviews in History. June 21, 2024. https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/2090.

- Henceforth, I always refer to the Kyiv reissue of Miller’s book as the most complete version, except in places where it is specified otherwise. Alexei Miller, Ukrainskiy vopros Rossiyskoy imperii [The Ukrainian Question of the Russian Empire], (Kyiv: Laurus, 2013), 268; Johannes Remy, Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 221. [↩]

- Anton Kotenko, “Imagining Modern Ukraїnica,” Ab Imperio 1 (2015): 521; Tomasz Stryjek, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Acta Poloniae Historica, no. 115 (2017): 321. [↩]

- Alexey Miller, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Scando-Slavica 63, no. 2 (2017): 231–34. [↩]

- Johannes Remy, “But That Is Not What I Wrote: Response to Alexey Miller’s Review of My Brothers or Enemies,” Scando-Slavica 64, no. 1 (2018): 112–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/00806765.2018.1446864. [↩]

- On the different occasions of Miller’s cooperation with Russian pro-government institutions, such as SVOP and Valdai Discussion Club, see Olga Bertelsen, “Russian Front Organizations and Western Academia,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 36, no. 4 (2023): 1189–1192, https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2022.2147807. [↩]

- Serhiy Bilenky, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 6, no. 1 (2019): 197–200; Andriy Zayarnyuk, review of Brothers Or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Reviews in History, June 21, 2024, https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/2090; Ostap Sereda, “‘Dity Rusi’: ‘Braty Chi Vorohy?’ Diskusiya Shchodo Ukrayins’koho Natsional’noho Rukhu Seredyny XIX Stolittia v Suchasniy Anhlomovniy Istoriohrafii [‘Children of Rus’: ‘Brothers or Enemies?’ Discussion on the Ukrainian National Movement of the Mid-19th Century in Contemporary English-Language Historiography],” Naukovi Zapysky UKU, no. 3 (2019): 293–300; Tomasz Hen-Konarski, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Krytyka, no. 3–4 (2017): 233–34; Olga Andriewsky, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Slavic Review 77, no. 1 (2018): 227–29, https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2018.29; Andrii Danylenko, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Slavonic and East European Review 95, no. 3 (2017): 568–70, https://doi.org/10.1353/see.2017.0034; Maxim Tarnawsky, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Canadian Slavonic Papers 60, no. 3–4 (2018): 616–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2018.1480696. [↩]

- Volodymyr Kravchenko, “Putting One and One Together? ‘Ukraine,’ ‘Malorossiia,’ and ‘Russia,’” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 20, no. 4 (2019): 823–40. https://doi.org/10.1353/kri.2019.0062; Denys Shatalov, “Brat’ya Ili Chinovniki? [Brothers or Officials?],” Ab Imperio, no. 1 (2018): 324–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0012; Stanislav Mohylnyi, review of Brothers or Enemies: The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, by Johannes Remy, Ab Imperio, no. 1 (2018): 316–23. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2018.0011. [↩]

- Stryjek, review of Brothers or Enemies, 319. [↩] [↩]

- Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 10. [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., IX. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 13; Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 4. [↩]

- Both mention this work in the Introduction, and the name index indicates the frequent citation of Savchenko in their works. See Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 13–14, 408; Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 9–10, 326. [↩]

- Serhiy Bilenky, Laboratory of Modernity, (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023), 194. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780228018582. [↩]

- Miller, review of Brother or Enemies, 232. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Miller, review of Brother or Enemies, 233. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Miller, review of Brother or Enemies, 234. [↩]

- Miller, review of Brothers or Enemies, 232. For more details about the Maksymovych-Pohodin dispute, see Alexei Tolochko, Kievskaya Rus’ i Malorossia v XIX veke [Kyivan Rus’ and Little Russia in the nineteenth century], (Kyiv: Laurus, 2021), 207–235. [↩]

- Remy, But That Is Not What I Wrote, 112. [↩]

- Bilenky, review of Brothers or Enemies, 198. [↩] [↩]

- Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 50. [↩]

- Miller, review of Brothers or Enemies, 233. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 79. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 324–325. [↩]

- Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 79, 89, 228. [↩]

- Spartak Aitov, “Ukrainska istoriohrafiia ta zhurnal ‘Osnova’ v konteksti kulturno-natsionalnoho vidrodzhennia Ukrainy [Ukrainian Historiography and the Journal ‘Osnova’ in the Context of the Cultural and National Revival of Ukraine]” (dys. kand. ist. nauk, Dnipropetrovskyi natsionalnyi universytet, 2001), 73–75. [↩]

- Miller, review of Brothers or Enemies, 232. [↩] [↩]

- Stryjek, review of Brothers or Enemies, 316. [↩]

- Mohylnyi, review of Brothers or Enemies, 320. [↩]

- Kravchenko, “Putting One and One Together,” 834. [↩]

- Miller, review of Brothers or Enemies, 232–233. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 144, 326. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 207–213. [↩]

- Mohylnyi, review of Brothers or Enemies, 321. [↩]

- Remy, “But That Is Not What I Wrote,” 115. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Remy, “But That Is Not What I Wrote,” 116. [↩]

- Bilenky, review of Brothers or Enemies, 199. [↩] [↩]

- Tarnawsky, review of Brothers or Enemies, 617; Sereda, “Discussion on the Ukrainian National Movement,” 298; Bilenky, review of Brothers or Enemies, 199. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 207. [↩]

- Mykhaylo Gaukhman, review of Children of Rus’: Right-Bank Ukraine and the Invention of a Russian Nation, by Faith Hillis, Ab Imperio 2017, no. 3 (2017): 277–278. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 14–61. [↩]

- Remy, “But That Is Not What I Wrote,” 113-114. [↩]

- Bilenky, review of Brothers or Enemies,197. [↩]

- Kravchenko, “Putting One and One Together,” 833. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Zayarnyuk, review of Brothers or Enemies, https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/2090. [↩]

- Miller, review of Brothers or Enemies, 234. [↩] [↩]

- At the beginning, Remy also explains which specific documents interested him in the mentioned archives. See Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 8-9. [↩]

- Remy, “But That Is Not What I Wrote,” 114. [↩]

- Stryjek, review of Brothers or Enemies, 320. [↩]

- Kravchenko, “Putting One and One Together,” 832. [↩]

- Sereda, “Discussion on the Ukrainian National Movement,” 298–300. [↩]

- Johannes Remy—Academia.edu, June 21, 2024 [↩]

- Alexei Miller, “Ukrainskiy Vopros” v Politike Vlastey i Russkom Obshchestvennom Mnenii, Vtoraya Polovina XIX v. [“The Ukrainian Question” in the Policy of the Authorities and Russian Public Opinion, Second Half of the 19th Century], Saint Petersburg: Aleteyya, 2000. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 324. [↩]

- Shatalov, “Brothers or Officials,” 324–25. [↩]

- Tarnawsky, review of Brothers or Enemies, 617. [↩]

- UkrTube, “Brothers or Enemies: Ukrainian National Movement & Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, Johannes Remy,” YouTube, 15 December 2016, video, 00:46–00:52, June 21, 2024. [↩]

- Remy, Brothers or Enemies, X. [↩]

- Johannes Remy – Academia.edu, June 21, 2024, https://www.academia.edu/36262877/But_that_is_not_what_I_wrote_Response_to_Alexey_Millers_review_of_my_Brothers_or_Enemies [↩]

- Koselleck, Temporal layers, 27. [↩]

- Johannes Remy, review of Nationalisierung Der Religion: Russifizierungspolitik Und Ukrainische Nationsbildung, 1860–1920, by Ricarda Vuplius, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 9, no. 4 (2008): 980. https://doi.org/10.1353/kri.0.0036. [↩]

- Shatalov, “Brothers or Officials,” 326. [↩]

- The Ukrainian transcription of the name with the letter “ѣ” is “Kulish,” while the Russian transcription is “Kulesh.” [↩]

- On de-russification in the context of personal names, place names, and ethnonyms, see Oleksiy Gnatiuk and Anatoliy Melnychuk, “Housing Names to Suit Every Taste: Neoliberal Place-Making and Toponymic Commodification in Kyiv, Ukraine.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 65, no. 1 (2024): 34–63; Oleksiy Gnatiuk and Sergei Basik, “Performing Geopolitics of Toponymic Solidarity: The Case of Ukraine.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography 77, no. 2 (2023): 63–77. [↩]

- Remy, Brothers or Enemies, 9. [↩]

- Faith Hillis, Children of Rus’: Right-Bank Ukraine and the Invention of a Russian Nation, (Cornell University Press, 2013), 22; Alexei Miller, The Ukrainian Question: The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century (Budapest–New York: CEU Press, 2003), 54. [↩]

- Johannes Remy, “Censoring Ukrainian Patriotism in the Russian Empire: The Ban on the Second Printing of the History of the Rus′ in 1858.” Canadian Slavonic Papers 64, no. 2–3 (2022): 336. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 51-52. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 58. [↩] [↩]

- Skinner, “Meaning and Understanding in the History of Ideas,” 16. [↩]

- Klymentiy K. Fedevych, “Otvet Retsententam [Response to Reviewers],” Ab Imperio 2018, no. 2 (2018): 232-233. [↩]

- Theodore Weeks, “The Challenges of Writing a Multi-National History of the Russian Empire,” Ab Imperio 2008, no. 4 (2008): 370. [↩]

- Remy, review of Nationalisierung Der Religion, 977–87. [↩]

- Remy, review of Nationalisierung Der Religion, 978. [↩]

- Remy, review of Nationalisierung Der Religion, 984. [↩]

- Mykhaylo Gaukhman, “V Poiskakh Novoy Istorii: Istoriohraficheskie Diskussii Nachala XXI v. o Metanarrative Istoriyi Ukrainy [In Search of a New History: Historiographical Discussions at the Beginning of the 21st Century on the Metanarrative of Ukrainian History],” Ab Imperio, no. 3 (2022): 27–68. [↩]

- Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, “Beyond ‘Identity,’” 14, 19–20. [↩]

- Joseph, Language and Identity, 98. [↩]

- Volodymyr Masliychuk, review of Imperski Identychnosti v Ukrayinskiy Istoriyi XVIII – Pershoi Polovyni XIX St. [Imperial Identities in Ukrainian History from the 18th to the First Half of the 19th Century], by Vadym Adadurov and Volodymyr Sklokin, Ab Imperio, no. 4 (2020): 260. [↩]

- Alan Mikhail and Christine M. Philliou, “The Ottoman Empire and the Imperial Turn,” 721–22, 725. [↩]

- Illia Gerasimov and Marina Mogilner and Alexandr Semenov, eds., Myths and Misconceptions, 9. [↩]

- Hen-Konarski, review of Brothers or Enemies, 233. [↩]

- Yaroslav Hrytsak, “Mark von Hagen, ‘A Conscious Ukrainianist.’” Ab Imperio, no. 3 (2019): 237. [↩]

- UkrTube, “Brothers or Enemies: Ukrainian National Movement & Russia from the 1840s to the 1870s, Johannes Remy,” 16:03–16:14, June 21, 2024. [↩]

- Miller, The Ukrainian Question, 59. [↩]

- Alan Mikhail and Christine M. Philliou, “The Ottoman Empire and the Imperial Turn,” 730. [↩]

- Illia Gerasimov and Marina Mogilner and Alexandr Semenov, eds., Myths and Misconceptions, 30-31. [↩]

- Andrii Portnov, Istoriyi dlya domashn’oho vzhytku: Eseї pro Pols’ko-Rosiys’ko-Ukrayins’kyi trykutnyk pam’Yatі [Histories for Home Use: Essays on the Polish-Russian-Ukrainian Triangle of Memory], (Kyiv: Krytyka, 2013), 29–30. [↩]

- Michael David-Fox and Peter Holquist and Alexander M. Martin, “The Imperial Turn,” 707. [↩]

- The Russian Empire: A Multiethnic History (2001). Originally published in German (Russland als Vielvölkerreich: Entstehung, Geschichte, Zerfall, 1992); also available in Ukrainian (Rosiia yak polietnichna imperiia. Vynyknennia, istoriia, zanepad, 2005). [↩]

- Kravchenko, “Putting One and One Together,” 825. [↩]

- Kravchenko, “Putting One and One Together,” 839. [↩]