Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the international community swiftly imposed an unprecedented array of sanctions aimed at crippling the Russian economy and pressuring the Kremlin to cease its military aggression. However, despite the intensity and breadth of these measures, their effectiveness remains a contentious issue. This article delves into the impact of these sanctions on Russia’s economy, the strategies employed to circumvent them, and the broader implications for global trade and geopolitical stability.

The research was developed during the “Ukraine’s EU Integration: Compliance and Resilience in Times of War and Geopolitical Rivalries” course at the Invisible University for Ukraine, guided by Inna Melnykovska and Nazariy Stetsyk (Ivan Franko National University of Lviv) and prepared for publication in collaboration with Nadiia Chervinska (CEU). The research was supported by the Open Society University Network (OSUN) and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, the international community rapidly intensified sanctions against the aggressor country.1 The financial and banking sectors felt the impact acutely, heavily dependent as they were on access to Western financial institutions and markets. Many Western banks had to sever ties with Russian banks to comply with the sanctions, impacting their profits.2 Additionally, the EU implemented numerous trade measures against the Russian Federation. However, the effectiveness of the European Union’s sanctions remains uncertain. Although statistics indicate some damage to the Russian economy, the predicted drastic impact has not yet been observed. In 2022, the emergence of new mechanisms for circumventing sanctions by Russian banks, businesses, individuals, and legal entities, as well as the strengthening of state cooperation with Asian countries, has somewhat compensated for the lost trade with the EU.

Russia has been finding new ways to access new markets and intensify trade with China, Turkey, Belarus, and Central Asian countries, using their financial systems for transactions.3 Export restrictions are also debatable: according to Demertzis et al. (2022), rising prices have caused Russia’s export revenue to increase by over forty percent, reaching almost $120 billion this year, contrary to expectations of a decline. Similarly, other sanctioned countries have been finding loopholes and maintaining economic indicators. For example, North Korea has kept oil prices stable, Iran has used a shadow network of 39 entities to access the international financial system,4 and Syria has created new shell companies.5

Even sanctions targeting Russian individuals affiliated with Putin’s regime appear to have limited impact. Despite the EU sanctioning a total of 1,473 people and 207 entities since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, including earlier individual sanctions,6 these measures have not significantly undermined the Kremlin system. According to Snegovaya,7 the sanctions effort in 2022 has not compromised the decision-making capability or the operational efficiency of those targeted, who include key figures in decision-making, the upper class, and sectors like propaganda and military operations. Furthermore, EU sanctions seem to disproportionately affect the middle and lower classes, leading to a decrease in their incomes.8 This echoes the situation in other sanctioned countries, such as Iran, where sanctions have resulted in a 3.8 percentage point increase in poverty.9 The human cost of these sanctions is frequently so significant that it discourages political reform and instead turns the citizens of the sanctioned countries against sanctioning bodies.10 This raises questions about the real effectiveness of sanctions in reaching their intended aims and contributing to conflict resolution.

Therefore, in this paper, I aim to examine the impact of sanctions on the Russian economy, particularly in banking and financial sectors, their effectiveness and potential regime change, and investigate the loopholes employed to surpass them.

As mentioned before, Russia is the most sanctioned country in the world right now. A total of 14,081 restrictions have been imposed on individuals, companies, vehicles, and aircraft linked to the country, with 11,327 placed after February 22, 2022. This surge in sanctions followed the Russian government’s declaration of recognizing the independence of the separatist Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DPR and LPR) and the subsequent deployment of troops into other Ukrainian regions. These actions prompted immediate responses from the EU, the U.S., Australia, and others. Before the full-scale invasion in 2022, Russia was already under sanctions for the temporary occupation of Crimea and Sevastopol in 2014, involvement in cyber attacks, arms trade with North Korea, Iran, and Syria, and the use of chemical weapons.

International sanctions, even if their goals are clear, may have several paradoxical outcomes. Afesorgbor11 shows that trade flows between the sanctioning and targeted countries decrease once sanctions are enforced. However, trade increases when sanctions are merely threatened, supposedly due to stockpiling in anticipation of penalties to limit potential negative effects.

One of the arguments made in favor of sanctions is that they put pressure on people to take action and seek governmental change, in the hope of softening or lifting the sanctions. However, sanctions often pressure the political elite, achieving the opposite of their intended effect.12 As a result, rulers may use violence to maintain their positions. The research evidence suggests that imposed restrictive mechanisms do not alter the sanctioned nation’s foreign policy in the direction the sanctioning nations desire,13 and are politically damaging only domestically in less autocratic states.14 Aidt and Albornoz15 suggest that foreign intervention to destabilize an autocracy is most likely when the local elite is weak and foreign investors are powerful. If a revolution occurs in the targeted country, the political-economy model suggests that the political elite reduces the supply of public goods, lowering the income and increasing the costs of rebellion for citizens.16 For example, despite the U.S. using a mix of sanctions, diplomatic inducements, and threats of military intervention to deprive Iran of foreign investments in oil and energy, these measures have not led to the desired regime change.17

Another issue with sanctions is the loopholes that allow target countries to avoid the imposed restrictions. For example, while sanctions on Iran have affected its national economic growth rates, inflation, consumer price index, and other indicators,18 they have not been completely tight. The Obama administration did not impose restrictions on gold exports to Iran despite having legal authority to do so under Executive Order 13622 since July 2012. This loophole allowed Iran to increase its gold imports and establish energy-gold trade with countries like Turkey, India, and China.19

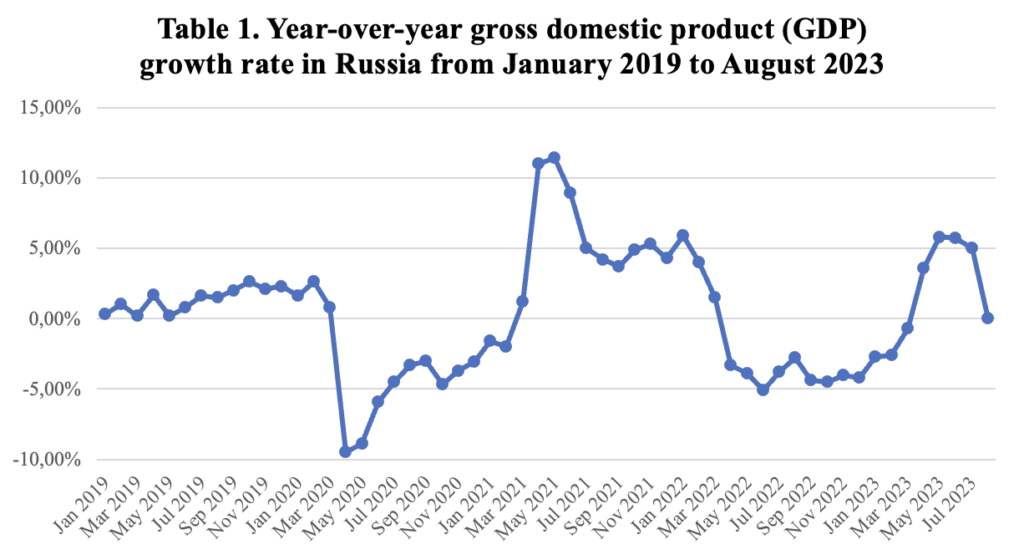

Crozet & Hinz20 found that since 2014, sanctions on Russia have caused a loss in global trade amounting to $1.8 billion. The burden on private actors is unequally spread among Western nations, with 92% of the expense falling on EU Member States. Additionally, 87% of the lost commerce has been caused by non-embargoed goods. Dreger et. al.21 report that oil prices have a greater influence on the Russian ruble than sanctions, which only impact conditional volatility in Russia when unanticipated. Meanwhile, economic sanctions are unlikely to shift Russia’s political course or resolve the war with Ukraine in the long term. Data presented in Table 1 confirms that sanctions imposed on Russia since February 24, 2022, have only temporarily reduced Russia’s GDP.

Source: Dreger, C., Kholodilin, K. A., Ulbricht, D., & Fidrmuc, J. (2016). Between the hammer and the anvil: The impact of economic sanctions and oil prices on Russia’s ruble. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(2), 295–308.

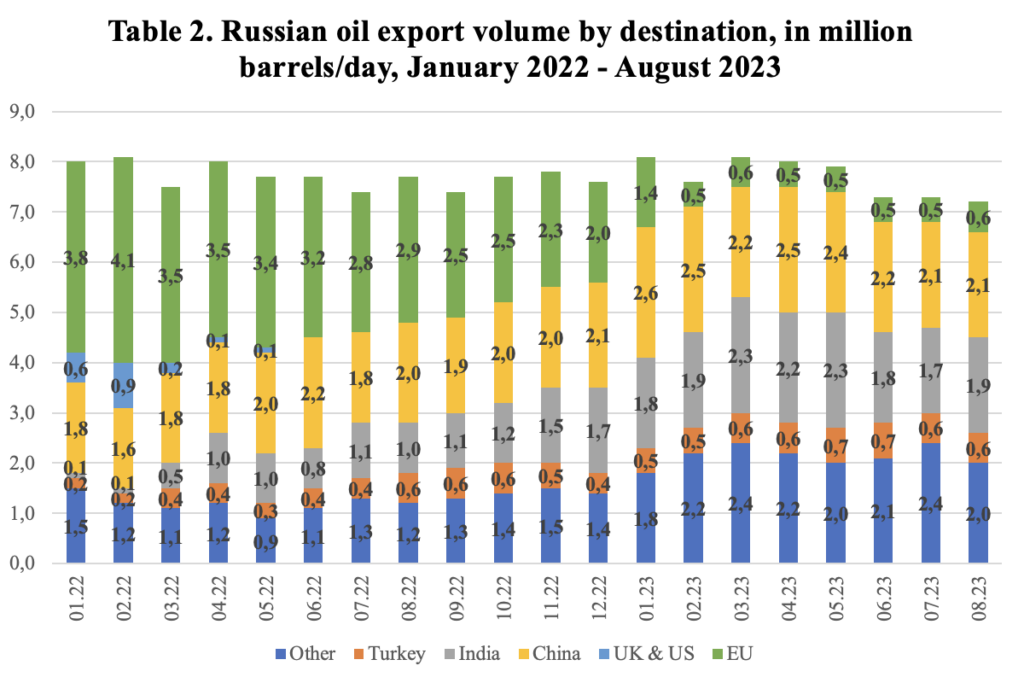

COVID-19 had a more significant impact on GDP growth than the sanctions imposed due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For instance, GDP dropped to its lowest at -9.5 % in April 2020, while the most substantial effect reached by sanctions was -5.1% in June 2022. Moreover, since late 2022, there has been a steady increase in Russian GDP, signifying that the sanctions’ effects were short-lived and compensated by increased trade with other countries. In 2022, Russia achieved a trade surplus of approximately $291.5 billion, marking a 53.6% increase from 2021.22 Despite losing around $100 billion in oil exports and $40 billion in natural gas earnings since the full-scale invasion, data presented in Table 2 shows that Russia managed to mitigate these losses by providing gas discounts, which attracted Asian countries to cooperate. The financial and banking sectors also show evidence of sanctions evasion, although these are less quantifiable compared to the energy sector.

Source: Hilgenstock, B., Pavytska, Y., & Ivanchuk, V. (2023). “Sanctions Impact Exports and the Ruble, but Continued Effectiveness Needs to Be Ensured.” KSE Insitute.

Imposing financial restrictions on Russia presents several potential scenarios for the development of the global payment system. According to Baicu and Oehler-Șincai,23 financial sanctions may accelerate the creation of alternative payment methods, including the use of cryptocurrencies for cross-border transactions. They may also challenge the dominance of the American dollar in the global monetary system and accelerate the internationalization of the Chinese yuan. Following the EU’s fifth package of sanctions, the largest Russian banks, such as Sberbank, VTB, and Alfa-Bank, were prohibited from transactions with securities. However, these banks responded by transferring their clients’ foreign assets to brokers like BKS and ATON.24 Kubin25 examined the impact of sanctions on these banks and other corporations, finding a weak impact in 2015-2017 with some improvement in 2018-2019. Moreover, banking sanctions are anticipated to have relatively limited direct consequences since Russia’s digital ecosystems are embedded within the domestic banking system.26 With the withdrawal of international payment systems like Visa and Mastercard, Russian consumers began to obtain cards in Belarusian banks to pay for foreign services and subscriptions to the App Store and Google Play. Russian banks switched to the local payment system MIR and the Chinese payment system UnionPay, which continue to operate, although their capacity for international transactions is limited.27

Russia’s efforts to bridge the technological gap through import substitution have shown much clearer benefits than introducing significant changes to the tax and organizational structures of the petroleum industry, which have resulted in unanticipated expenses for both the government and the sector.28 Since December 2022, there has been evidence that Russia and Iran are building a new trade route to the Indian Ocean, increasing their resilience against Western sanctions.29 Other studies investigating the impact of sanctions at the firm level indicate that while these do not consistently impair the operational capabilities of Russian companies, they do require strategic adjustments.30

According to political leaders, sanctions are imposed to limit the Kremlin’s capacity to fund the war and reduce Russia’s economic foundation.31 The EU’s officially stated aims also include inflicting significant political and economic costs on Russia’s ruling class, which is intended to erode Putin’s support and catalyze regime change. However, as previously analyzed, the effectiveness of sanctions aimed at regime change can be assessed as largely unsuccessful. Measures such as freezing assets or imposing travel bans are undoubtedly important but generally failed to reach intended political objectives.

When sanctions are devised to curtail financing of military aggression, it is crucial that they are both comprehensive and do not allow for easy alternatives, such as:

- There are many loopholes for Russia to bypass the trade restrictions using third-party countries that trade with the sanctioning states. When one or more nations refuse to trade with Russia, this opens up opportunities for other nations to collaborate and trade under more favorable terms.32

- The SWIFT ban proved much less effective than anticipated, even though it was one of the most discussed measures introduced in response to the full-scale invasion. Russian banks and citizens easily avoid these financial restrictions through a variety of loopholes, including the use of MIR payment cards, opening bank accounts in post-Soviet countries, and utilizing Asian payment systems. This suggests that financial sanctions alone may not significantly influence Russia’s economy and its ability to finance the war. One approach could be to look for alternative measures that impact Russia’s ability to finance the war, rather than promote regime change, with a strategic focus on:

— disrupting supply chains of components essential for weapon and military-related machinery construction. This field is extensively monitored by the United States.33 However, the effects are nullified if other countries do not take action. For instance, Switzerland has exported microelectronic components worth $276, 000 to Russia, which have been used to construct drones, rockets, and cruise missiles. Additionally, Russia compensates for trade losses through purchases from Serbia, Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Georgia.34 Consequently, while sanctioning these specific supply chains shows promise, alternative trading routes and sourcing from other nations continue to undermine the impact.

— implementing a punitive tax on Russia’s oil, which could prove economically beneficial for the rest of the world while imposing a significant burden on Russia. The proposal to introduce a calculated tax of 90% could be a way to shift the burden onto the supplier since Russia needs to sustain supply to export markets while consumer demand remains flexible due to indifference to oil’s origin and sensitivity to its price, This would expropriate the rent while maintaining Russian gas on the market.35

— promoting a “brain drain” from Putin’s closest circle to destabilize the regime’s strategic capabilities in the war and eventually stop it.

It is important for national leaders and policymakers to critically evaluate the sanctions imposed on Russia to increase their effectiveness. The goal of these sanctions should focus on slowing the economy to diminish Russia’s ability to finance the war rather than pursuing outright regime change. By monitoring and sanctioning alternative ways of acquiring sanctioned products, introducing punitive taxes, and facilitating the outflow of key intellectual figures away from the Russian leadership, the world could reach significant outcomes.

- Zandt, F. (2023, February 22). The World’s Most-Sanctioned Countries. Statista Daily Data. https://www.statista.com/chart/27015/number-of-currently-active-sanctions-by-target-country/ [↩]

- Clapp, S., & Immenkamp, B. (2022). Russia’s war on Ukraine: EU sanctions in 2022. Policy Commons. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2325117/russias-war-on-ukraine/3085649/ [↩]

- Hirsch, P. (2022, December 6). Why sanctions against Russia aren’t working — yet. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2022/12/06/1140120485/why-the-sanctions-against-russia-arent-working-yet and Venkataramakrishnan, S. (2023, April 9). Russians search for bootleg solutions to overcome payments sanctions | Financial Times. Financial Times. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/faf49f59-d059-48b9-98c3-6b1d675cfba9 [↩]

- United States Department of State, & Blinken, A. J. (2023, March 9). Designating Iran Sanctions Evasion Networks [Press release]. https://www.state.gov/designating-iran-sanctions-evasion-networks/ [↩]

- Fox, T. (2022, October 19). Syria using maze of shell companies to avoid sanctions on Assad regime’s elite. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/mar/22/syria-using-maze-of-shell-companies-to-avoid-sanctions-on-assad-regimes-elite [↩]

- Council of the EU. (2022, February 23). EU adopts package of sanctions in response to Russian recognition of the non-government controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine and sending of troops into the region [Press release]. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/02/23/russian-recognition-of-the-non-government-controlled-areas-of-the-donetsk-and-luhansk-oblasts-of-ukraine-as-independent-entities-eu-adopts-package-of-sanctions/?utm_source=dsms-auto&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=EU%20adopts%20package%20of%20sanctions%20in%20response%20to%20Russian%20recognition%20of%20the%20non-government%20controlled%20areas%20of%20the%20Donetsk%20and%20Luhansk%20oblasts%20of%20Ukraine%20and%20sending%20of%20troops%20into%20the%20region [↩]

- Snegovaya, M., Dolbaia, T., Fenton, N., & Bergmann, M. (2023). Russia Sanctions at One Year. https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-sanctions-one-year [↩]

- Berriault, L. (2022). Russia under sanctions. GIS Reports. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/russia-sanctions/ [↩]

- Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2016). The impact of US sanctions on poverty. Journal of Development Economics, 121, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.03.005 [↩]

- Demarais, A. (2022). Backfire: How Sanctions Reshape the World Against U.S. Interests. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/dema19990 [↩]

- Afesorgbor, S. K. (2019). The impact of economic sanctions on international trade: How do threatened sanctions compare with imposed sanctions? European Journal of Political Economy, 56, 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.06.002 [↩]

- Gutmann, J., Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2022). The Impact of Economic Sanctions on Target Countries: A Review of the Empirical Evidence. EconPol Forum, 24(3), 5–9. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/272171 [↩]

- Afontsev, S. (2022). Political paradoxes of economic sanctions. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 92(S13), S1225–S1229. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1019331622190029 [↩]

- Allen, S. H. (2008). The domestic political costs of economic sanctions. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(6), 916–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002708325044 [↩]

- Aidt, T. S., & Albornoz, F. (2011). Political regimes and foreign intervention. Journal of Development Economics, 94(2), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.01.016 [↩]

- Oechslin, M. (2014). Targeting autocrats: Economic sanctions and regime change. European Journal of Political Economy, 36, 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.07.003 [↩]

- Monshipouri, M., & Boggio, G. D. (2022). Sanctions, deterrence, regime change: A new look at US‐Iran relations. Middle East Policy, 29(4), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/mepo.12661 [↩]

- Salitskii, A. I., Zhao, X., & Yurtaev, V. (2017). Sanctions and import substitution as exemplified by the experience of Iran and China. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1019331617020058 [↩]

- Clark, G., Ziemba, R., & Dubowitz, M. (2012). Iran’s Golden Loophole. Roubini Global Economics. [↩]

- Crozet, M., & Hinz, J. (2020). Friendly fire: the trade impact of the Russia sanctions and counter-sanctions. Economic Policy, 35(101), 97–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiaa006 [↩]

- Dreger, C., Kholodilin, K. A., Ulbricht, D., & Fidrmuc, J. (2016). Between the hammer and the anvil: The impact of economic sanctions and oil prices on Russia’s ruble. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(2), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2015.12.010 [↩]

- WTO, & Statista. (April 30, 2023). Russia: Trade balance of goods from 2012 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars) [Graph]. In Statista. Retrieved December 27, 2023, from https://www-statista-com.nukweb.nuk.uni-lj.si/statistics/263634/trade-balance-of-goods-in-russia/ [↩]

- Baicu, C. G., & Oehler-Șincai, I. M. (2022). European Union’S Financial Sanctions Against Russia – Implications For The International Payment System. Euroinfo, 6(3), 3–17. [↩]

- Kontrakty.UA. (2022, April 8). Російські банки намагаються обійти санкції. Єрмак розповів, як саме. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://kontrakty.ua/article/195548 [↩]

- Kubin, T. (2023). Russia, Ukraine, and the West: Are Smart Economic Sanctions Effective? The Soviet and Post-soviet Review, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.30965/18763324-bja10082 [↩]

- Allinger, K., Barisitz, S., & A., T. (2021). Russia’s Large Fintechs and Digital Ecosystems–in the Face of War and sanctions. Focus on European Economic Integration, 3, 47–65. [↩]

- Vlasyuk, V. (2022, May 25). 10 Ways of Bypassing Sanctions That the Russians Resort To. Ekonomichna Pravda. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.epravda.com.ua/columns/2022/05/25/687436/ [↩]

- Vatansever, A. (2020). Put over a barrel? “Smart” sanctions, petroleum and statecraft in Russia. Energy Research and Social Science, 69, 101607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101607 [↩]

- Dhyani, A. (2023). Russia and Iran New Route Bypassing Western Sanctions. The Geopolitics. https://pure.jgu.edu.in/id/eprint/5538 [↩]

- Gaur, A., Settles, A., & Väätänen, J. (2023). Do Economic Sanctions Work? Evidence from the Russia‐Ukraine Conflict. Journal of Management Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12933 and Meyer, K. E., Fang, T., Panibratov, A., Peng, M. W., & Gaur, A. (2023). International business under sanctions. Journal of World Business, 58(2), 101426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2023.101426 [↩]

- European Commission. (n.d.). EU sanctions against Russia following the invasion of Ukraine. EU Solidarity With Ukraine. Retrieved October 14, 2023, from https://eu-solidarity-ukraine.ec.europa.eu/eu-sanctions-against-russia-following-invasion-ukraine_en [↩]

- Takeda, M. (2023). Sanctions on Russia will work, but slowly. East Asia Forum. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2023/01/10/sanctions-on-russia-will-work-but-slowly/ [↩]

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023, August 28). With over 300 sanctions, U.S. targets Russia’s circumvention and evasion, Military-Industrial supply chains, and future energy revenues. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1494 [↩]

- Sonnenfeld, J. A., & Wyrebkowski, M. (2023, September 7). The dangerous loophole in Western sanctions on Russia. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/07/western-sanctions-russia-ukraine-war/ and Swissinfo. (2023, June 15). Russia may be using Swiss micro-electronic components for offensive. swissinfo.ch. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/business/swiss-high-tech-micro-electronic-components-used-in-russia-s-military-offensive/48592162 [↩]

- Hausmann, R. (2022, March 3). The case for a punitive tax on Russian oil. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/case-for-punitive-tax-on-russian-oil-by-ricardo-hausmann-2022-02 [↩]