Following Bohdan Krawchenko’s intellectual trajectory, this conversation offers a look at how Ukrainian identities and institutions have been sustained and reconfigured across decades, continents, and shifting political contexts. It links Krawchenko’s student activism and community building in Canada, his engagement in Ukraine’s state-building after 1991, and the establishment of educational institutions in Central Asia.

The conversation is published in two parts. It was recorded during a discussion organized at the Invisible University for Ukraine Summer School 2025, “Beyond the Post-Soviet: Rethinking Environmental, Social, and Cultural Agency in Wartime Ukraine” (1–10 July 2025, Budapest), and was moderated by Ostap Sereda and Nadiia Chervinska.

Ostap Sereda

Professor Krawchenko, thank you for accepting our invitation and for agreeing to discuss your views and projects in these rapidly changing times. You are often described as a prominent representative of a generation of Ukrainian left intellectuals in the West who emerged in the 1960s and 70s. What were the main developments in Ukrainian émigré politics and institutions that preceded this generation, and what kind of environment did this create for your own intellectual formation?

Bohdan Krawchenko

First, thank you for having me. I hope you will find this discussion interesting. Your question raises a critical point about the understudied phases and evolution of émigré political life. I will begin by summarizing the main developments. The post-1917 revolutionary period produced political émigrés in the classical sense, concentrated primarily in France and Czechoslovakia. In the latter, with support from Presidents Masaryk and Beneš, a veritable “Ukrainian Piedmont” emerged. The authorities there supported thousands of emigrants and students, fostering major Ukrainian institutions, such as the Free Ukrainian University, the Ukrainian Higher Pedagogical Institute, the Ukrainian Studio of Plastic Arts, and the Ukrainian Economic-Cooperative Faculty. This ecosystem also included the Ukrainian Institute of Sociology—headed by a socialist revolutionary—which had an affiliated workers’ university and a press that published journals and books like Mykyta Shapoval’s Sotsiolohiia ukrainskoho vidrodzhennia. Politically, this milieu was a diverse hub, encompassing former officials of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and Skoropadsky’s Hetmanate, activists from the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers’ Movement, and the Socialist-Revolutionaries. It also served as the birthplace of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). This vibrant period ended abruptly with the Nazi and subsequent Soviet occupations, which inflicted another discontinuity on Ukraine’s political tradition.

The post-WWII diaspora political landscape, however, was quite different. Around 2.3 million Ukrainian SSR citizens had been taken to Germany as forced labourers. While most returned after the war, approximately 250,000 became Displaced Persons (DPs) in camps in the American and British zones. Demographically, 70-80 percent were from pre-WWII Polish, Romanian, and Czechoslovak territories; only about 60,000 were from central or eastern Ukraine, the latter including a small group from the industrial centres. Though most DPs were young and from peasant or working-class backgrounds, a crucial core of intellectuals, professionals, and political activists from Galicia and Czechoslovakia had also fled to avoid Soviet repression. Living in camps with ample free time due to a lack of employment, they channeled their energy into education, culture, and religion. This activism energized the community and prevented the apathy seen in other DP contexts, creating ideal conditions for political mobilization. They spent about three years in these camps (1945-48) before systematic resettlement began.

Within the camps, the OUN-Bandera faction (OUN-B) emerged as the dominant political force. With about 5,000 members in postwar Germany, it was the only significant political organization and aggressively attempted to hegemonize all spheres of Ukrainian life.

In contrast, the Ukrainian National Rada, representing the government-in-exile, had only 200 members, and there were only a few Skoropadsky supporters. The Banderites promoted an ideology of integral nationalism, which placed the nation above all, advocated for an authoritarian Ukrainian state, and emphasized action, strength, and willpower. They often viewed Ukrainian DPs from the core lands (“naddnipriantsi”) with disdain for their perceived weak national consciousness, considering them in need of “re-education.”

It is important to note a key ideological shift that occurred within Ukraine during this time. In 1943, the OUN and UPA created the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR), led by Roman Shukhevych. Influenced by reports from Eastern Ukraine, it replaced integral nationalism with a program promoting democratic rights. However, this shift had little impact on the diaspora Banderites in the DP camps, who remained rooted in European interwar authoritarian traditions.

The OUN-B’s primary postwar political project was the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN), a Munich-based coalition that lobbied Western governments for the independence of nations subjugated by the USSR. Yet, as a nationalist, conservative, and often authoritarian-right alliance, it remained politically marginal, and this marginality continued into the modern era. In 1992, in Ukraine, the OUN-B was reconstituted as a political party—the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (CUN). Led by Slava Stetsko, it remained a fringe far-right group, a fact evidenced by its candidate receiving only 1.6% of the vote in the 2019 presidential election and 0.04% in parliamentary elections. Despite its minimal role, the group has been effectively exploited by pro-Kremlin propaganda to tarnish Ukraine’s political culture.

DP groups who disagreed with the Banderites or hailed from outside Galicia formed their own smaller organizations. Eastern Ukrainians, who were Orthodox, organized around the Autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

In 1946, the Ukrainian Revolutionary-Democratic Party (URDP) was founded. Led by the celebrated writer Ivan Bahrianyi, it became the largest political group among the Eastern Ukrainian émigrés. The URDP advocated for a “democratic nationalism,” standing in stark contrast to OUN-B’s integral nationalism.

Crucially, they believed that meaningful change in Ukraine would ultimately have to emerge from within the USSR, predicting that autonomist forces would eventually gain momentum.

In 1990, URDP changed its name to the Ukrainian Republican Democratic Party. A left-wing faction of URDP emerged and published a monthly newspaper, Vpered (Forward, 1949-59), which featured articles on developments in Soviet Ukraine, international politics, and émigré life from a democratic socialist perspective. Its editorial board comprised a roster of prominent intellectuals, including Ivan Maistrenko (a former Borot’bist), Vsevolod Holubnychyi (an economist), Borys Levytsky (a political analyst), Hryhoriy Kostiuk (a literary critic), and others. Decades later, when a new Ukrainian left-wing intellectual group emerged around the journal Diialoh in the 1980s, the Vpered group formally dissolved itself, passing the torch to a new generation.

Most of the 35,000 Displaced Persons who arrived in Canada starting in 1947 settled in Toronto and nearby areas, with smaller groups in Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Montreal. The 1950s experienced strong economic growth, social conformity—especially regarding gender roles—high birth rates, an expanding welfare state, growing consumerism, and the appearance of “teenage culture.” Canada differed from the USA, where approximately 80,000 Ukrainians had settled. It had a more liberal and socially oriented political culture. It saw itself as a “cultural mosaic” rather than a “melting pot,” and lacked powerful ultra-conservative, anti-communist movements like the John Birch Society or McCarthyism. Canada had a Progressive Conservative Party that was critical of the USSR and supported Ukraine, which also introduced major social programs and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

The Canadian context allowed émigrés to find employment easily, support their children’s education, and donate to establish new Ukrainian organizations that addressed social, cultural, and educational needs.

The role of the OUN-B’s community organization was significant, with youth groups, Saturday schools, dance groups, and choirs forming the core of community life. Others from Galicia organized Plast, which, like the OUN-B youth group, promoted Ukrainian patriotism. Political activity was mainly limited to calls for a free Ukraine made at community events. The new émigré community could not effectively explain the Ukrainian struggle to Canadians generally or to the 360,000 Ukrainian Canadians concentrated in the Prairie Provinces, many of whom had lost fluency in their heritage language since settling in 1891. This task fell to English-speaking intelligentsia and professionals who understood Canadian society. The “baby boomers,” born after 1946, began to take on this work.

Ostap Sereda

How did your generation differ from your parents? What were the main sources of inspiration for you when you were a student? And why did you not join one of the established trends in Ukrainian political and intellectual life, for example, hetmanivtsi?

Bohdan Krawchenko

In 1947, my parents moved from Germany to France, and in 1951, they emigrated to Canada, settling in Montreal, Quebec. We became part of a small “Easterners” (“skhidniaky”) community. When I was 11, we moved to a farm southeast of Montreal, away from the organized Ukrainian community. My Ukrainian political identity was shaped at home, on the fields, with my father from Dnipropetrovsk oblast, who was deported to Vologda during the first wave of dekulakization. He escaped at 13, walked back to Ukraine, and worked in Donbas. Steeped in Cossack history, he became a Hetmanite in the DP camps. He emphasized building state institutions and the army, distrusted social movements, and criticized Dontsov as an “ideologue of racial hatred.” We argued about social movements. My first political advocacy was in grade ten, when I won a Rotary Club speech contest on supporting Ukrainian aspirations, which was reported in Montreal’s daily.

The 1960s were a period of significant social and cultural change and saw the emergence of a generation with distinctive attitudes. The post-war boom led to a significant expansion of higher education, creating conditions for a new generation to explore new ideas. Young Ukrainians in Canada during the 1960s had one of the highest university attendance rates of any ethnic group. This became a new factor in community life.

Like many other young Ukrainian Canadians, I had little clue about what was happening in Ukraine. Prague 1968 offered hope, but the situation in Ukraine seemed hopeless.

But I was deeply impacted by two things. In 1966, I saw Parazhanov’s Shadows of our Forgotten Ancestors at a French cinema house, and in 1969, I bought the Chornovil Papers at a regular bookstore and read it cover to cover on a park bench. Then, in 1970, Dziuba’s book Internationalism or Russification was issued by a UK publisher. This was a bolt of optimism—there was something to relate; it spurred me to do graduate studies as a way of pursuing my interest in Ukraine.

The growth of the university student population put new wind in the sails of the Ukrainian Canadian Students’ Union (SUSK), established in 1953. Moreover, in this period, the first post-war Ukrainians secured university positions which fostered a new intellectual climate in the community. SUSK, under the leadership of Roman Serbyn and Roman Petryshyn, sought to energize the organization by appointing “field workers” to travel across the country and mobilize Ukrainian students. Serbyn had begun teaching at McGill University in Montreal, while Petryshyn was a graduate student at Lakehead University and a civil servant in the Toronto Citizenship Branch.

I was a student at Bishop’s University in the Eastern Townships, a traditional Anglo stronghold with limited interaction with Quebec society. Meanwhile, Quebec was experiencing the “Quiet Revolution,” challenging its conservative, clerical society and leading to rapid modernization. The Parti Québécois was sovereigntist, seeking independence or special status, and social democratic. The Union générale des étudiants du Québec (UGEQ), inspired by syndicalism, called for major educational reform. I was editor of the weekly student newspaper, advocating for change at the university and greater openness to Quebec society. My activist record caught the attention of SUSK leadership, who offered me a summer “field worker” position. My “hippie-like manner (complete with sandals)” tended to shock the conservative Ukrainian community, though students seemed to welcome it. At the 1969 SUSK Congress, I was elected President.

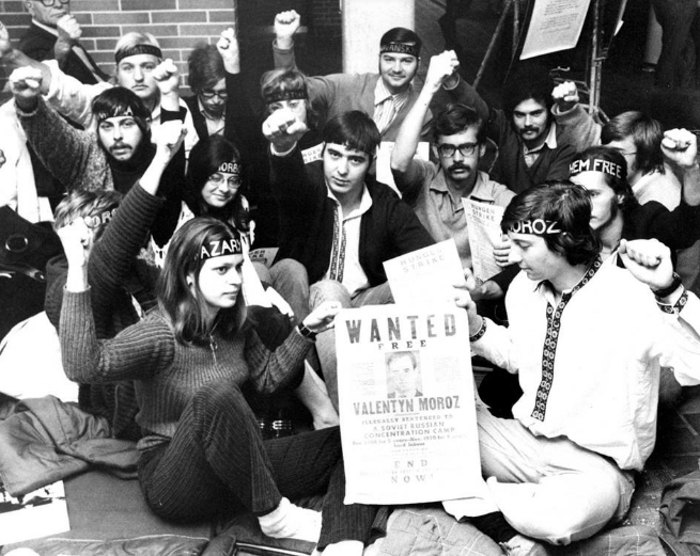

The SUSK mobilization agenda focused on Ukrainian existence within Canada. This activism was sparked by the federal government’s Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, established in response to Quebec’s aspirations. When the Commission’s Book IV was released in 1969, it predicted a future where ethnic groups would assimilate into one of Canada’s two dominant cultures. SUSK offered a different vision: a bilingual, multicultural Canada. We argued that cultural diversity was a vital and enriching reality that should be officially recognized. Simultaneously, we prioritized community development, inspired by new social activism models, analyzing community needs and implementing measures to meet them. This activism aligned with growing interest in Ukraine, fueled by the rise of the dissident movement. The mass arrests starting in 1972 galvanized this new cohort into Ukraine-oriented political activity. Student leaders, such as Marco Bojcun, formed an independent committee to defend political prisoners, operating separately from existing émigré political groups. Marco later moved to the UK where he emerged as a leading Ukrainian socialist intellectual and played an active role in the left-wing Ukraine Solidarity Campaign.

In 1969-70, SUSK deployed several fieldworkers across Canada, focusing on mobilizing support for multiculturalism as an alternative to government policy. We held conferences on multiculturalism in various cities, and the Toronto one, attended by Commission members, was particularly impactful.

An important result of SUSK’s activities was that we brought into Ukrainian community life people from earlier generations by discussing real issues rather than symbolic nationalism.

It was during this time that Manoly Lupul became involved. A third-generation Ukrainian born in a northern Alberta bloc settlement, Harvard PhD, and professor at the University of Alberta, he became a leading advocate for multiculturalism and the founding Director of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS). In 1973, Canada was officially declared multicultural, and SUSK played a significant role in this achievement.

The Ukrainian community in Alberta saw remarkable development because it benefited from the influence of prominent figures such as Albert Hohol, a provincial Minister of Advanced Education, Laurence Decore, Mayor of Edmonton, Julian Koziak, Minister of Education, and Peter Savaryn, the eminence gris of the Alberta Provincial Conservative Party under Premier Peter Lougheed and subsequently Chancellor of the University of Alberta. Apart from CIUS, which was publicly funded, the Ukrainian-Bilingual Programme was established in schools, and the Ukrainian Cultural Village, a major open-air museum with costumed interpreters was opened not far from Edmonton. When Premier Lougheed attended the opening of the Village in 1974, he spoke to a crowd of some 15,000. It was reportedly the largest audience he ever addressed.

Nadiia Chervinska

You became the director of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) in 1986, 10 years after its establishment. Under your leadership, CIUS became more than just a research center: it published books, provided grants, and developed infrastructure for Ukrainian studies in Canada, becoming one of the most important Ukrainian research centers at that time. What was your vision of CIUS and its priorities? Do you think that the Ukrainian diaspora’s expectations somehow influenced the intellectual agenda of the institute?

Bohdan Krawchenko

CIUS was an unusual institution. It was established because the Alberta government increased the university’s budget following community lobbying. This meant its mission was primarily driven by the community, not the university faculty. Part of CIUS’s remit was to support Ukrainian studies nationally and internationally, rather than expanding university-based research. Led by Lupul and Savaryn, CIUS’s community base was the Ukrainian Canadian Professional and Business Federation (P&B), whose members were mostly Canadian-born. They charted an educational ladder which began with Ukrainian kindergartens, bilingual elementary and some secondary classes, and culminated in the Institute at the university. In 1976, Lupul became CIUS director. Roman Petryshyn and I, both former student activists, were the first research associates. I also held a cross-appointment with the Political Science department, where I introduced a course on politics in contemporary Ukraine.

CIUS pioneered studies and publications on Ukrainian Canadian history and social dynamics. Frances Swyripa, a third-generation Ukrainian Canadian, was appointed as a research associate and made significant contributions. There was also a Ukrainian language centre that promoted innovative bilingual education pedagogy and produced learning resources for schools. A relevant effort for today’s large diaspora was the report we produced, “Building the Future: Ukrainians in Canada in Alberta,” a community development roadmap. John-Paul Himka, an expert on Galician history, joined CIUS and became Professor of Ukrainian and East European History after the untimely death of Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky in 1984, an erudite scholar who enriched intellectual life.

CIUS played a singular role in filling the void in English language literature on 19th– and 20th-century Ukraine. Scores of books appeared on the contemporary period, some as co-publications with Macmillan Publishers, brought CIUS to international attention.

We also published important Ukrainian language books, such as Mykola Zerov’s Lektsii z istorii ukrains’koi literatury, 1798-1870 (Lectures on the History of Ukrainian Literature, 1798-1870), Hryhoriy Kostyuk’s phenomenal memoirs Zystrichi i proschannia: spohady (Meetings and Farewells: Memories) in two volumes, and Ivan Maistrenko Istoria moho pokolinnia: spohady uchasnyka revolutsijnyh podiy v Ukraini (The History of My Generation: Memoirs of a Participant in Revolutionary Events in Ukraine). Over the years CIUS has published more than 100 books.

The 5-volume Encyclopedia of Ukraine, published by the University of Toronto Press, funded by the governments of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, as well as the P&B Federation was our biggest project. It is a huge building bloc in the Ukrainian knowledge edifice. It was managed by CIUS’ Toronto office, headed by the late Professor Danylo Struk, where another major undertaking is underway—the translation and annotation of Hrushevsky’s ten-volume History of Ukraine-Rus’.

We undertook numerous initiatives, among them supporting the launch of courses in Ukrainian studies at several universities across Canada and in Brazil, built a library collection that includes an impressive microfilm collection of statistical sources and studies published in Ukraine in the 1920s and early 1930s, and initiated engagement with Ukraine in 1988, signing exchange agreements with Lviv University and the Institute of Literature of the National Academy of Sciences, hosting, among other scholars, Serhii Plokhy at the start of his stellar career. In 1989-90, CIUS received nearly 100 academics from Ukraine.

Returning to the initial question about the diaspora’s role in shaping the CIUS agenda, the post-war immigration strengthened the Ukrainian community, but it was the efforts of the earlier community that enabled public funding for institution building. But, when we began fundraising for endowments, the first responders were those who came to Canada as DPs. Thanks to donations such as Petro Jacyk’s, the largest ever received by the university, we established a Ukrainian history research centre. The children of that generation also became a vital audience, providing resources to shape and promote a values-based discourse on Ukraine.

However, the core political leaders of émigré organizations committed to integral nationalism posed challenges. The commemorations of the 50th anniversary of the man-made famine in Ukraine (1982-83) in Edmonton were a case in point. The new leadership of the Edmonton branch of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress in Alberta led the committee that organized our actions, and I was a member of this committee. We resisted the attempts of the aforementioned group to shape the discourse and derail our efforts to mainstream the commemorations. The daily newspaper, the Edmonton Journal, carried a four-page supplement on that famine, which I edited. The first public monument to the Holodomor was erected outside City Hall (at that time, Laurence Decore served as the mayor of Edmonton and was the leader of the Alberta Liberal Party). The unveiling of the modernist sculpture by Ludmilla Temertey began with a meeting at another location, where the Premier of the Province spoke, and I delivered the keynote address. Thousands of people, including a significant number of non-Ukrainians, then marched through the streets to the city center.

Ostap Sereda

Besides Ukrainian studies, you were also involved in the East European and Soviet studies, and co-founded the Critique, Journal of Socialist Theory. It seems like you were quite critical about what was going on in the field and were trying to change the main trends.

Bohdan Krawchenko

After completing my master’s degree at the University of Toronto and serving as SUSK president, I went to the Institute for Soviet and East European Studies at the University of Glasgow to pursue a similar degree, focusing on the economy and social structure. While in Canada, I became particularly interested in political sociology and the study of social movements, especially since these had engulfed Western Europe, and apart from Prague ‘68, there were also protests in Poland and Yugoslavia. I arrived holding broadly left-wing views. Their relevance was reinforced by what I saw in Glasgow—a restless working class that faced unemployment and lived in a district, the Gorbals, that was straight out of Engels’ Conditions of the Working Class in England.

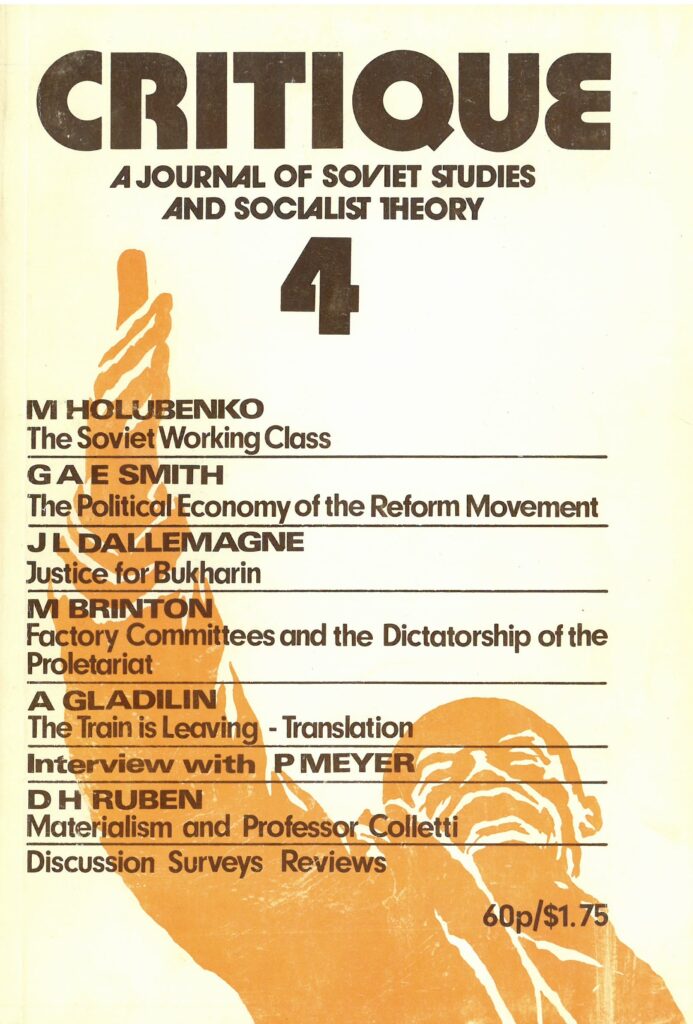

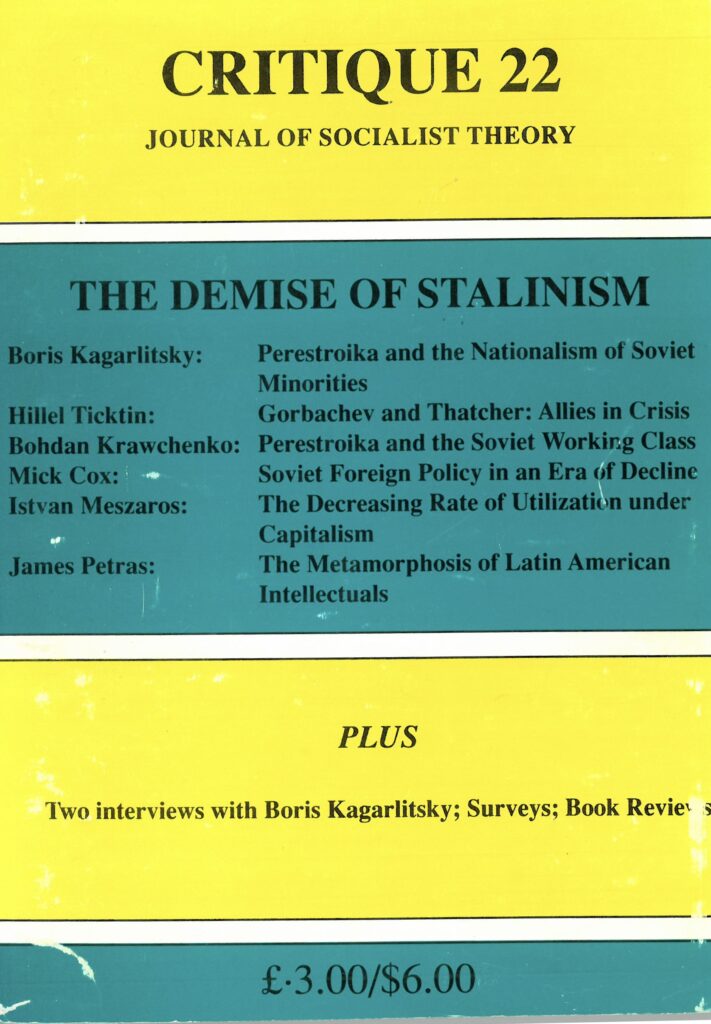

In Glasgow, I met Hillel Ticktin, a lecturer from South Africa who went on scholarship to Moscow to avoid arrest for opposing apartheid. He was an anti-Stalinist Marxist and developed a rigorous, critical analysis of the Soviet Union. The student cohort was a remarkable mix of leftists who enjoyed heated debate. The analysis was so novel and compelling that we felt it needed broader communication. I was probably the first to suggest a journal, which appeared in 1973, following two Critique conferences in 1972—one in Glasgow and another in London, attended by over 400 people. Clearly, there was a big demand for a left-wing critique of the USSR based on solid thinking.

The main point was that the USSR was an unstable and unsustainable social formation, destined to collapse. It lacked inherent laws of motion and objective economic mechanisms to drive rational development, making systemic waste an intrinsic feature of the system.

We articulated this analysis at a time when neither the left nor the right understood these fundamental issues, and for their own reasons, were strongly opposed to recognizing them. Critique articles analyzed the nature of the ruling group and their intrinsic insecurity, as well as the unique mechanisms of social control, which resulted in one of the most atomized societies in human history. My article “The Soviet Working Class: Discontent and Opposition” appeared in the 4th issue of the journal (under a pseudonym). Critique is still going strong. One of the outcomes of this analysis convinced me that the disintegration of the USSR and Ukraine’s independence were inevitable—the only question was when.

Nadiia Chervinska

In your study of Ukrainian nationalism from a socio-economic perspective, you brought the topic of nationalism to Marxist studies in a new way and changed the traditional approach from which nationalism was studied by Ukrainian scholars. What do you think was the most revolutionary moment for that particular kind of intellectual setting of the 1980s?

Bohdan Krawchenko

My engagement with the Critique circle provided me with a method and framework for thinking, rather than final answers. My research was driven by the practical utility of my political engagement. I wanted to know if Ukraine would become independent, and why we lost the 1917 revolution. Did social change, urbanization, and Russification make mobilization around national demands unlikely? These questions led me to study Ukraine’s social-economic history starting in the 19th century. I also examined the 18th century to understand the distortions in Ukraine’s social structure following its incorporation into the Russian Empire.

To answer my questions, I did a lot of empirical research to gather data and read thousands of pages of newspapers to gain a deeper understanding of what was happening. Using internal colonialism as a theoretical framework required empirical evidence.

Careful analysis of Soviet census and statistical sources revealed a cultural division of labour and Russification that hindered social mobility among Ukrainian youth.

For example, the Ukrainian working class, except in the Baltics, had the highest secondary education completion rate, yet their university admission rates were only better than those of the Tajiks, who were in last place among the 15 republics. Protests against the restriction of national rights stemmed not only from national cultural sentiment but also from significant social factors. The first mass demonstrations in the 1990s were miners’ protests, calling for Ukraine to take control of its economy. Industry conditions were dire due to a lack of investment in modernizing mines. Small wonder: the Moscow centre sequestered a third of Ukraine’s budget revenues to finance projects in Russia.

My work analyzed the broader economic and social structural forces that framed the national project. However, these factors do not solely dictate events. As Sartre pointed out in his In Search of a Method, you have to explore the “question of mediation,” that is, how a society becomes aware of itself and constitutes its own history through collective action and movement. Social movements, revolutions, collective actions, and political conflicts can accelerate the shaping of nation states, as Charles Tilly noted. This meant using different methods and sources to understand the dynamics of each of the periods of Ukrainian history.

Ostap Sereda

It is very ironic that you had to be involved in neoliberalization in Ukraine in the 1990s, while having a left-wing intellectual and political commitment. Was there any kind of leftist alternative out there that could represent the negotiation with state policy in the early 1990s or maybe after 2004. Is there a leftwing alternative in the Ukrainian political context now?

Bohdan Krawchenko

Today, the organized left is small, but it exists. I just attended a meeting of Cуспільний рух (Social Movement). It was a detailed discussion of additional hazard pay for workers in strategic infrastructure that is constantly under fire. There were several score trade unionists attending. The Social Movement is creating platforms to bring people together to discuss real issues. Alas, donors are not lining up to support these kinds of initiatives.

There is vast discontent with corruption, social inequalities, lack of enforcement of labour legislation, paltry social payments while the salaries of certain organs of the state get huge salary increases. Yet, no political party occupies the social democratic space to organically represent this workforce and its potential allies among the educated class.

It is a conundrum that Ukraine’s vibrant civil society has not given rise to a viable political party to contest elections, even at the local level. Without this development, there is a real danger that these legitimate societal grievances will be exploited by populists.

Was there an alternative at that time? There were other alternatives, but there was no political force or lobby that could advance them. In the early years, the overriding concern was building state institutions. When the international financial organization arrived, they found no interlocutors to debate policy. There were virtually no civil servants with knowledge of market economics or international perspectives to consider various options, and they were preoccupied with practical questions arising from the economic crisis. The Western heavy artillery and consultants arrived with economic reform plans that were implemented in Poland, as well as what was happening in Russia under Gaidar. An alternative plan would have needed human capacity and time. The Washington Consensus, with its neoliberal policies, prevailed. One of its axioms was that there should be no industrial policy. However, one could have conducted an inventory of viable assets and endowments that could foster growth.

Additionally, one could have established workers’ and employees’ committees at each enterprise to prevent the rapacious stripping of assets. With industrial collapse, it was obvious that employment would have to be generated by small and medium enterprises, and policies could have advanced this. When people speak of Poland’s economic success, it is often overlooked that its precondition was decentralization and the development of strong local governments, which spurred local economic growth and prevented large-scale asset stripping.

This conversation is published in two parts—read the second part here.