The essay explores the construction of the myth of Ukrainian ‘peasant-ness’ as a national characteristic in the 19th century, shaped by both intellectual discourse and imperial policies. Through an analysis of the correspondence of Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Kostomarov, and Panteleimon Kulish, it underlines the class-based origins of national stereotypes and further contextualizes this process within broader discussions on myth-making, nationalism, and imperial discourse.

The article was developed during the “History of the Public Sphere in Ukraine and East Central Europe” course at the Invisible University for Ukraine, directed by Ostap Dereda. The research was guided by Oleksiy Rudenko (CEU) and prepared for publication in collaboration with Yevhen Yashchuk (University of Oxford) and Marta Haiduchok (CEU). The research was supported by the Open Society University Network and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst.

According to George Schöpflin’s definition, a myth is an invisible part of social consciousness that holds human collectives together.1 Contrary to popular ideas, rather than opposing reality, myths reflect the symbolic structures prevalent in society. Hence, the only difference between ‘facts’ and ‘myths’ lies in representation – facts directly mirror reality, while myths convey it figuratively. Building on such framework, this paper explores how the myth of Ukrainian ‘peasant-ness’ was shaped as a national characteristic through intellectual discourse and imperial policies in the 19th century. In particular, it examines the writings of key figures of the Ukrainian cultural canon, Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Kostomarov, and Panteleimon Kulish to trace how their works contributed to either constructing or contesting the notion of Ukrainians’ ‘peasant-ness.’

Nation, one of the forms of human grouping, expresses humanity’s tendency to create myths. The concept of the ‘nation’ is relatively recent compared to the ancient origins of ‘myth.’ Nevertheless, we still can find traces of archaic myth properties in the 19th-century national ideas.2 Many Ukrainian national myths lie on the surface of public discourses while being constantly subjected to revision. Thus are, for example, the myths of Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Ukraiinska Povstanska Armia), Holodomor or Taras Shevchenko. All of them share a common mythical character. There is a representation of these subjects in the national public consciousness, which may not differ from reality, but the national public consciousness narrows the view of looking at it. In such interpretations, the members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army appear as exclusively moral fighters for the independence of the Ukrainian nation; the Holodomor is exclusively an attempt to destroy the Ukrainian nation; and Shevchenko is exclusively a poet of the national idea. Examining the Ukrainian case reveals that the myth lacks nuance, remaining static within the population groups which share it.

The absence of doubt implies selectivity and, therefore, the existence of a selector. Constructivist historians insisted that all categories of identity and other conceptual aspects of human life did not arise naturally but were implemented by specific individuals in agreement with social or personal interests. Describing various spheres of human existence and the influence exerted on them by particular power structures Judith Butler,3 Michel Foucault,4 Edward Said,5 and others highlight that identities exhibit a dynamic nature, devoid of fixed or predetermined attributes, arising as socially contingent constructs. As a tool for interpreting reality, a myth cannot be invented; instead, it can be constructed while grounded in the imperative of possessing a particular experience. Hence, the closer a myth aligns with reality, the more imperceptible its mythical nature becomes over time.

According to Liah Grinfeld’s division of the development of nationalism into stages, the first stage is structural.6 It is characterised by structural transformation within dominant social groups that leads to a crisis of their traditional identities and a search for new forms of self-expression. The vague term ‘structural transformation’ includes social, economic and cultural transformations triggered by changing conditions in the broader societal context. Thus, the original idea of the nation and nationalism is, firstly, a coincidence that includes the current interests of the intelligentsia and, secondly, a somewhat random reaction to societal changes.7 For example, this can be traced to the processes connected with the formation of Ukrainian nationalism in the 19th century. Despite the old-fashioned status of Romanticism in literature, philosophy and art in the early 1860s, the typical Romantic concern for codifying literary language continued to dominate the Ukrainian cultural imagination. The creative activity of Taras Shevchenko solved the ‘language problem’ that lay at the heart of the Ukrainian intellectual community in favour of the Central-Ukrainian national language. Having made its debut in journalism and science, particularly in the St. Petersburg magazine ‘Osnova,’ the Ukrainian literary language was banned from publication in the Russian Empire by the Valuev Circular of 1863 and the Ems Ukaz of 1876. From the perspective of Greenfeld’s concept, the empire’s policy regarding the Ukrainian language can be interpreted as both a disruption of the nation-formation process as well as the crisis of traditional identity expression.

In response to such a situation, the leading Ukrainian thinkers of that time proposed several alternatives for developing Ukrainian culture, which envisaged the parallel existence of Ukrainian and Russian literature in Ukraine. All these alternatives, particularly those whose authors were Mykola Kostomarov, Panteleimon Kulish and Mykhailo Drahomanov, neglected the unfavourable position of the Ukrainian language in the empire. Therefore, the final result of their propositions would most likely be the complete assimilation of Ukrainian literature into Russian literature. Another solution to the problem was printing Ukrainian-language works outside the Russian Empire, in neighbouring Austrian Galicia.8 None of the answers could provide the Ukrainian language with the necessary exposure for the nation-building process as it was eliminated from the public sphere. Despite the ban on printing in Ukrainian, the importance of the external representation of Ukrainian-ness remained. The situational response to the limitation was compensating for language with other ways of expressing identity.

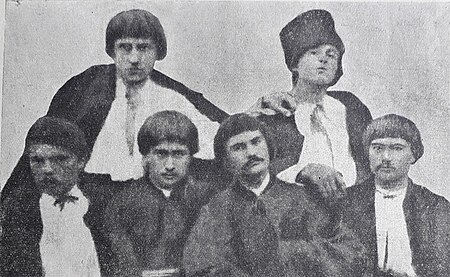

Various intellectual groups were illegally formed and developed during the second half of the 19th century, with their activities ultimately leading to the Ukrainian national revival. Due to the lack of opportunities for self-expression in public, they focused on manifesting empathy with Ukrainian-ness within their personal space. But what defined Ukrainian-ness except for the language, the autonomy of which was repeatedly questioned? Due to Ukrainian-ness being associated with the peasantry, the solution was found in wearing peasant clothes and hairstyles, eating peasant food, or generally imitation of the peasant way of life in public. Despite the sympathy of intellectuals for the ‘lower classes,’ their actual mode of existence was qualitatively different from that of the ‘common people.’ Accommodated to the comfort and not ready to entirely give it up, ‘khlopomans’ and other imitators of the peasant class were engaged in what Yekelchyk called ‘intellectual bricolage.’9 They singled out from the mass of features of peasant life only those that did not require extraordinary concessions with welfare, implementing chosen ones into their daily lives. For example, Drahomanov wrote about how different variations of ‘common-men’ (muzhytskiy) clothes were picked to play the role of national costume. Also, Mykhailo Starytskyi mentioned that he and Mykola Lysenko had a serious debate about which costumes they should buy. On the one hand, such selectivity served the convenience of the national narrative for contemporaries. On the other hand, it also provided evidence for the fabrication of the myth of the Ukrainian nation’s peasant-ness.

Examining the authors’ life experiences championing the ideas of national liberation and their expressed opinions in correspondence reveals a lack of consensus in their perceptions of Ukrainian-ness and, consequently, the Ukrainian peasantry. Illustratively, Kulish stands as a notable example when compared with other members of the ‘Ukrainian triumvirate’ – Taras Shevchenko and Mykola Kostomarov. Kulish’s worldview resulted from his humble origin and intellectual upbringing. Even though his family could not be called poor, Kulish could not pay the expenses for studying at St. Volodymyr’s University in Kyiv. There, he was noticed by Mykhailo Maksymovych, one of the founders of imperial ethnography, who became Kulish’s inspiration. Maksymovych involved Kulish in projects aimed at making the Polonized southwestern regions of the empire ‘Russian’ again. In addition, through his friendship with Maksimovych, Kulish became acquainted with Pyotr Pletnev, a poet and critic who denied the existence of both a separate Ukrainian language and Ukrainian identity.10 Kulish also maintained relations with Ivan Aksakov, a writer who contributed to including Kulish in the circles of the Slavophile magazine Russkaya Beseda. In his letters, Kulish spoke positively about Aksakov and his ‘patriotic’ activities until his death, ad mortem. Considering Kulish’s tendency to exclude everyone with whom he disagreed from his life, his relationship with Aksakov was solid. In a letter to Vasyl Bilozerskyi, Ukrainian philologist and ethnographer, Kulish described one of his meetings with Aksakov:

I met Ivan Aksakov, a staff captain, near Moscow. He is well done in national clothes [ed. Kulish is referring to his Great Russian suit] and he is happy that having retired, he will get the right to wear it.11

From the positive characterization given by Kulish, Aksakov’s views and their manifestation did not go beyond his own moral categories. Kulish was in an environment that did not see the division of society by nationalities but rather by classes. For many of his friends, the question of the existence of separate national units within the empire and friction between them did not exist. Instead, the problem was only class discord:

Today, at the dinner given by the merchants to the heroes of Sevastopol […], Kokorev wanted to make a speech about the estates that do not participate in public holidays and proposed a toast to the union of peasants, burghers, merchants, and nobles into one Great Russian nation.12

Kulish’s attitude towards Ukrainian-ness was somewhat ambivalent. Although he advocated the popularisation of everything Ukrainian, it needs to be clarified what this ‘Ukrainian’ meant to him. Unlike Shevchenko, who called himself Ukrainian in his letters and deliberately used the toponym ‘Ukraine,’ Kulish rarely dared to outline his national identity. Moreover, from his letters, one gets the impression that for him, Ukrainians were a peasant class rather than something else. As evidence, Kulish did not describe himself as one of the Ukrainians because he did not associate himself with the peasant class and its problems. According to imperial logic, ‘Little Russia’ peasants were Ukrainians by nationality. In addition, a universal characteristic of all peasants was ignorance. From this point of view, intellectuals could not consider it necessary to define themselves as part of Ukrainian-ness. Contrary to Kulish’s beliefs that: “[…] it is difficult to meet an educated Ukrainian who would not recognize himself as a Ukrainian,” he was not too inclined to openly call himself a Ukrainian.13 The connotations of peasant-ness and simultaneously ignorance, which went hand in hand with the manifestation of belonging to Ukrainian-ness, were so strong that Kulish did not refer to his‘Motherland’ (Rodina) in any other way than ‘Malorossiya’ in his letters.

Additionally, in Kulish’s correspondence, contemptuous attitudes towards Ukrainian-ness were sometimes traced. After arriving in Lubny, Kulish wrote the following to Bilozersky:

Now, we are forever provided with borscht, varenyky and other items of basic need. What more could a lazy khokhol wish for? Our proverb reads: “If there were bread and clothes, a Cossack would eat lying down.”14

Kulish called the Ukrainians ‘khokhols’, naming varenyky and borscht as their primary food in 1853 when the national myth with national culture and its attributes was only at the initial stage of formation. From this, we can assume that some of the attributes of what we now consider to be a fundamental component of traditional culture, particularly varenyky and borscht, existed in connection with imperial stereotypes about Ukrainian-ness even before they became part of the national myth. In addition, Kulish’s use of the derogative term ‘khohol’ indicates his affiliation with the imperial narrative of Ukrainian-ness. He did not use the equally common term ‘maloros’ but chose a stereotyped word instead. Kulish used this term in its original sense, which Prince Ivan Dolgoruky also used in 1818. The latter described the khokhols as uneducated and lazy people who were hardworking under proper management. Unlike other definitions of Ukrainians, such as ‘maloros,’ the term ‘khohol’ was characterized not only by ethnic but also by class alienation. If a maloros was a Ukrainian whose class affiliation was uncertain, then a khohol was always a peasant.15

The exclusivity of Kulish’s view was emphasized by the worldview of Shevchenko and Kostomarov, who, already in the 19th century, perceived Ukrainian-ness as a nationality, rather than a class. Fueling the interests of a particular nation in the world of multiple nationalisms, the ideology of nationalism was based on the opposition between ‘us’ and ‘them’.16 The letters of Shevchenko and Kostomarov confirm the transition from the imperial identity of citizenship to the national one. Both of them called the peasants no other than ‘compatriots.’ At the same time, both spoke negatively about certain persons based not on their class of origin but on their nationality. For Kostomarov, potential brides from Russian Saratov were unsuitable because they were ‘muscovites,’17 and for Shevchenko, the seamstress he hired could not cope with the work because she was a ‘damned muscovite.’18 In addition to showing hostility towards the ‘muscovites,‘ Shevchenko tried to give a voice to the Ukrainian peasantry in his own way. In a letter to poet Hryhoriy Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, Shevchenko asked the recipient to send ‘a blouse, a plakhta [ed. unstitched wrap skirt] and two ribbons’ to authentically portray a Ukrainian peasant girl in the picture.19 In addition, he conducted various ethnographic investigations, during which he tried to describe:

The types that exist in Ukraine, either by history or by beauty, secondly – how the current people live, thirdly – how they once lived and what they produced.20

Along with others who inspired the Ukrainian cultural revival, Shevchenko tried not to create something new, but to shift perceptions of the familiar. Contrary to the classic view of society as rigidly divided into social eatates, the intelligentsia undertook the mission of giving Ukrainian peasants national self-awareness. Even considering the importance of such a mission, not all Ukrainian figures refused the estates categorization of society at that time. The problem of the imperial narrative was not only with the conceptualisation of ‘Ukrainian-ness’ as ‘peasant-ness’ but also with ‘ignorance,’ which resulted from belonging to the peasantry. The close association between ‘Ukrainian-ness’ and ‘peasant-ness’ was so strong that it automatically linked the Ukrainian identity to a lack of literacy, implying that those who identified as Ukrainian were assumed to be uneducated. Undoubtedly, such ideas played into the hands of the empire because they were at odds with what Ukrainian intellectuals considered themselves to be. An illustration of those who succumbed to this narrative was Kulish, who did not manifest Ukrainian identity on convenient occasions. Considering that Kulish supported the spread of education among Ukrainians, he perceived Ukrainians as non-educated. To breathe a sigh of relief, the imperial policy did not require the destruction of the Ukrainian language but the absolute impossibility of its association with high culture. Activists of the imperial Russian culture pretended not to notice the division of society on the ethnic principle but, aware of the danger, nurtured class stereotypes, which partly coincided with national ones. Kulish partially confirmed that it was impossible to completely abandon the stereotypes of the empire while simultaneously being subject to it.

The emergence of Ukrainian nationalism in the 19th century was a complex period characterized by a fervent creation of national culture amidst the constraints imposed by imperial powers. This era witnessed a delicate dance between the aspirations of emerging Romantic, proto-nationalist movements and the limiting forces of imperial rule. Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Kostomarov, and Panteleimon Kulish embodied different perspectives that shaped Ukrainian identity during this time. While Shevchenko and Kostomarov interpreted Ukrainian identity as distinctly separate from imperial hegemony, Kulish’s stance was marked by ambivalence, reflecting the complexities of identity formation within a imperial context. The examples provided demonstrate not only the existence of conflicting identities within individuals but also the possibility of their mutual influence, as well as the fineness of boundaries between them. A myth of Ukrainians ‘peasant-ness‘ did not result from a singular event but rather from the complex process of transformation of class identity into a national one, influenced by a very particular socio-political reality. In subsequent years, the association of Ukraine with its ‘peasant origins’ contributed to the overshadowing of its other cultural dimensions, relegating them to the periphery of significance. Throughout the post-WWII Soviet era, a phenomenon known today as ‘sharovarshchyna’21 had popularized, characterized by the portrayal of Ukrainian culture through superficial, pseudo-authentic rural elements: from household paraphernalia to attire.22 This shift marked a final departure from the 19th-century Romantic vision of ‘peasant-ness’ as a basis for national and class liberation, towards its imperial and later Soviet reinterpretation as a sign of cultural backwardness.

[1] Schöpflin, George. “The Functions of Myth and a Taxonomy of Myth’s: Myths and Nationhood, ed. George Schöpflin and Geoffrey Hosking, Routledge, 2013 (first published 1997), p. 20.

[2] Ibid, p. 21-35.

[3] Butler described gender identity as not natural, but as one that gets actualized through practice of performance of its attributes. See in: Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Routledge, 2002.

[4] Foucault, while being mostly preoccupied with power relation dynamics, insisted that social institutions play a significant role in shaping identities. See in: Foucault, Michel. Society Must Be Defended. Lectures at the Collège de France 1975–76, 2003.

[5] Said claimed that despite the lack of relation to reality some of the stereotypes about the Orient became part of its identity thanks to the constant influence of the Occident. See in: Said, Edward W. Orientalism. Pantheon Books, 1978.

[6] Greenfeld, Liah. Nationalism: Five roads to modernity. Harvard University Press, 1992. p. 7.

[7] Ibid, p. 9

[8] Yekelchyk, Serhy. “The Nation’s Clothes: Constructing a Ukrainian High Culture in the Russian Empire, 1860-1900.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas no. 2 (2001), pp. 230-239.

[9] Єкельчик, Сергій. Українофіли: світ українських патріотів другої половини ХІХ ст. КІС, 2010, 20 c.

See also in: T. Nahaiko, “Ukrainophilism as World Outlook Paradigm of Community Movement in Historical Discourse”, Pereyaslav Litopys, vol. 9, 2016, p. 92

[10] Pelech, Orest. “The State and the Ukrainian Triumvirate in the Russian Empire, 1831–17.” In Ukrainian Past, Ukrainian Present: Selected Papers from the Fourth World Congress for Soviet and East European Studies, Harrogate, 1990, pp. 1-17. Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

[11] Гирич, Ігор. Пантелеймон Куліш. Повне зібрання творів. Листи. Т. II. Критика, 2009, с. 267.

[12] Там само, с. 335.

[13] Куліш, Пантелеймон. “Простонародность вь украинськой словесності”. Науково-педагогічна спадщина (Вибрані твори), 2008, c. 208.

[14] Гирич, Ігор. Пантелеймон Куліш. Повне зібрання творів. Листи… с. 118.

[15] Рябчук, Микола. “Хохли, малороси, бандери: стереотип українця у російській культурі та його політична інструменталізація” Наукові записки Інституту політичних і етнонаціональних досліджень ім. ІФ Кураса НАН України, №. 1, 2016, c. 179-194.

[16] Андерсон, Бенедикт. Уявлені спільноти. Роздуми про походження і поширення націоналізму. Критика, 2001.

[17] Листи до Тараса Шевченка. Наукова думка, 1993, с. 109.

[18] Шевченко, Тарас. Зібрання творів. Т. VI, Критика, 2003, с. 15.

[19] Там само, c. 14-15.

[20] Там само, c. 26-27.

[21] Though it’s hard to trace the exact origin of the term ‘sharovarschyna’ (Ukr. ‘шароварщина’), it is certainly related to the word ‘sharovary’ (Ukr. ‘шаровари’) in the Ukrainian language – means wide loose pants that originated in the East. In the Ukrainian context, ‘sharovary’ are usually associated with Cossacks and folk culture in general. See in: Єрмолаєва, Вікторія, та Нікішенко, Юлія. “Явище” шароварщини”: пошук дефініції”, Магістеріум: Культорогія, №. 68, 2017, c. 27-31.

[22] Там само, с. 29.