According to Opendatabot statistics, three major Ukrainian charity foundations—United 24, Come Back Alive, and Prytula Foundation—have raised more than 50 billion hryvnias for the needs of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and humanitarian needs in 2022 and 2023; this report, however, did not include other donation campaigns.1 Gathering donations for the national army is one of the methods used to mobilize civilians and give them a feeling of indirect participation in and contribution to the upcoming victory—that is how fundraising is perceived in Ukraine today. The calls for donations have filled social media: from private gatherings to large-scale campaigns led by charity funds or the state. Incidentally, the donations are often perceived as proof of patriotism, the nation’s economic strength, and an example of how common welfare and victory can prevail over individual interests. In a similar spirit, this article analyses fundraising efforts during World War I that supported the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Legion, a regiment formed within the Austro-Hungarian army. It addresses several key questions: What were the necessities of the USR Legion that required financing, and could the people contribute to this specific intention? What was the amount of donations, and what were the ways to fundraise?

The article was developed during the “Public History” course at the Invisible University for Ukraine, guided by Viktoriya Sereda (Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin / Ukrainian Catholic University) and Bohdan Shumylovych (Ukrainian Catholic University) and prepared for publication in collaboration with Nadiia Chervinska (CEU) and Mark Baker. The research was supported by the Open Society University Network (OSUN) and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

Ukrainian newspapers in Eastern Galicia announced the fundraising campaigns and reported on their progress in 1915. These campaigns mainly concerned the activities of the Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (Lehion Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv, USR)—a Ukrainian national regiment within the Austro-Hungarian Army. It is not the aim of this article to compare the donation campaigns during World War I and the current Russo-Ukrainian War. However, the financial donations to this earlier armed formation, reinforced by the national sentiments, were a bright sign of modernity as individuals realized their belonging to an imagined national community and strove to contribute to the common aims that the community perceived as vital.

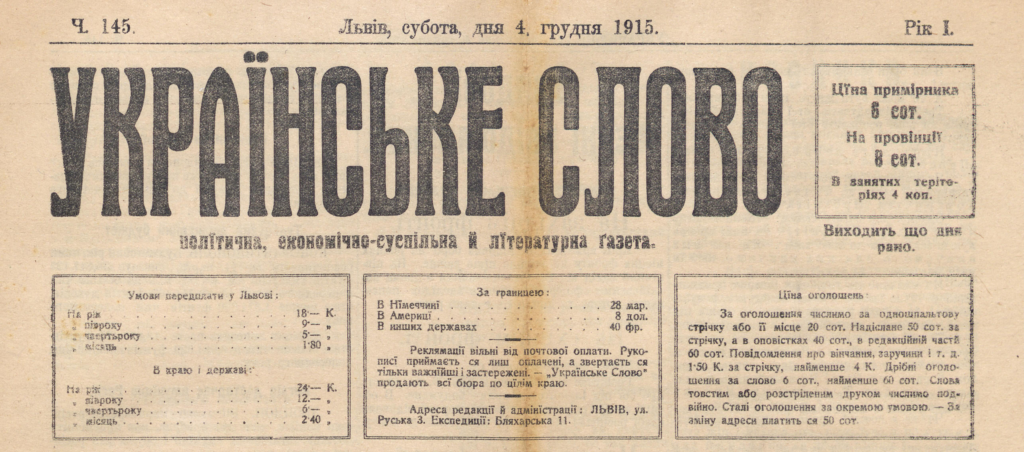

As a source, I chose the daily newspaper Ukrainske Slovo (The Ukrainian Word), published in Lviv from 1915–1918. Selected issues are available in the digital library of the Catholic University of Lublin (Poland), which is why I will analyze issues 73–170 (October–December 1915), the most continuous chronological range. The newspaper emerged after the Austrian recapture of Lviv from the Russian Army in June 1915. Indeed, as long as the active phase of hostilities on the Eastern Front lasted, the military theme was predominant in Ukrainske Slovo. Usually, an issue started with an overview of military actions and the proclamation documents of the Habsburg government or Ukrainian political institutions (for instance, the Supreme Ukrainian Council). Moreover, the newspaper presented the war from the Ukrainian perspective: the “national liberation” discourse was integral. Here, the Ukrainske Slovo editors promoted the USR, posting descriptions of the Legion’s military actions or life on the battlefield.2 The announcements and reports regarding the donations to the USR were usually posted in the final columns “Latest” (“Novynky”), “Announcements” (“Opovistky”), or in the separate “Donations” (“Zhertvy”) rubric. I focused on 25 donation reports in October–December 1915, analyzing them with quantitative methods.

“Let the Sun of Free Ukraine Rise on the Ruins of the Tsarist Empire!”

Divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, Ukrainian lands were the objects of imperial expansion plans. On the one hand, the Romanovs strove to capture Eastern Galicia, Bykovyna, and Transcarpathia, seeing them as primordial “Russian” territories that had to be united inside a single Russian state.3 On the other hand, the Habsburgs encroached mostly on the Balkans. However, their geopolitical plans also included the possibility of annexing Volhynia and Podillia and making them a part of a hypothetical Ukrainian autonomous territory inside the Danube monarchy.4

As the tension of an impending war was building, the Ukrainian intelligentsia in Galicia began to debate which side they would have to stand on. In December 1912, a meeting of a few Ukrainian political parties’ representatives in Lviv concluded: “In case of Austro-Hungarian armed conflict with Russia, the whole Ukrainian citizenship will decisively and unanimously place with their sympathies and actions on the side of Austria.”5 In July 1913, a student conference in Lviv made the same statement. A prominent argument was that these sympathies followed from comparing the empires, concluding that the Danubian monarchy was a “better” regime. At the same time, the incorporation of Galicia into Russia carried a risk of denationalization and assimilation.6 Shortly after the Great War began, the Supreme Ukrainian Council (Holovna Ukrainska Rada)—a newly formed organization that united three major Ukrainian parties in Galicia and aimed to represent Galician Ukrainians during the war—released a manifest to Ukrainian people on August 3, 1914. According to the manifest’s authors (Kost Levytskyi, Mykhailo Pavlyk, and others), while 30 million Ukrainians suffered under the Russian yoke, the Habsburg monarchy was a state “where Ukrainian national life found the freedom to develop”:

The Austro-Hungarian monarchy’s victory will be our victory. And the larger will be Russia’s defeat, the faster the time for the liberation of Ukraine will come. […]

Only those people have rights that can achieve them. Only those people have a history that can create it with decisive actions.

The Supreme Ukrainian Council calls you to action, with which You will achieve new rights, create a new period in your history, and take a proper place among the European people. Let this message find expression in every Ukrainian heart! Let it awaken an ancient Cossack zeal among our people! Let our society be not only a spectator but the most active participant in the upcoming events! Let [the society] employ all the material and moral powers for the defeat of Ukraine’s historical enemy!

To battle—to carry out the ideal that now unites all Ukrainian citizens! Let the sun of free Ukraine rise on the ruins of the tsarist empire!7

Presumably, the Supreme Ukrainian Council hoped for a better Habsburg attitude towards Ukrainians after the potential victory. Before the Great War broke out, there were negotiations between Ukrainian representatives and Viennese politicians regarding the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria province’s division into Western and Eastern parts; the latter would have been an autonomous Ukrainian subject of the Dual Monarchy.8 In addition, as Anna Veronika Wendland described, there was a vast “Russophile hysteria” during the last years before the war, followed by repressions and the exile of “disloyal” subjects. Even though the prevalence of Russophilia among Ukrainians and Greek Catholic clergy was exaggerated, it contributed to discrediting Ukrainians in Galicia.9

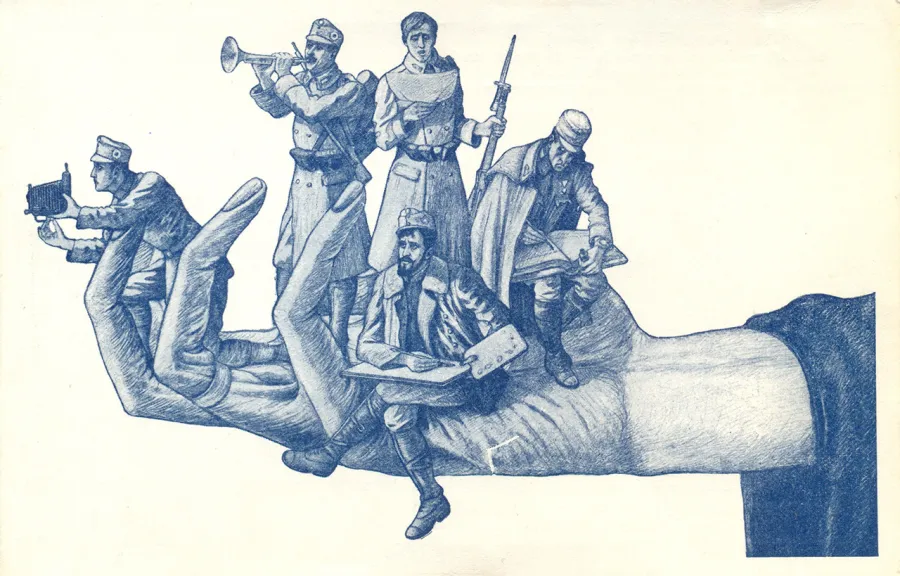

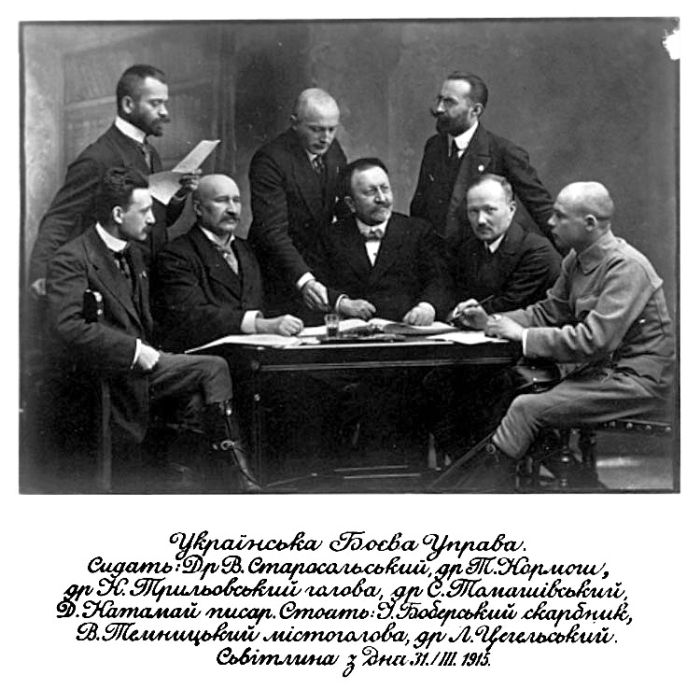

In that context, the Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen emerged. With the Supreme Ukrainian Council’s instruction, the special military commission, later known as the USR Military Board (Boiova Uprava USS) or the Ukrainian Military Board (Ukrainska Boiova Uprava, UMB), began organizing a Ukrainian national regiment at the beginning of August 1914. The Supreme Ukrainian Council and the UMB officially created this national regiment on August 6, 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia. In the proclamation concerning the Legion’s creation, the Supreme Ukrainian Council and the UMB addressed the Ukrainian people to enlist in the USR and make donations.10

Even though the Viennese government permitted the creation of a Ukrainian national regiment, central and local authorities hindered the USR’s organizational development. Approximately 28 thousand people expressed their readiness to enlist in the USR, but under pressure from Galician Polish politicians, the government limited the Legion’s personnel to 2.5 thousand. Also, the Austrian command recalled only sixteen Ukrainian officers from the Imperial-Royal Army to instruct the riflemen; the UMB requested a hundred officers. Furthermore, the government armed the riflemen with outdated Werndl–Holub rifles.11

Shortly after the USR departed for training, the Austrian command ordered them to enter military action on September 10, due to the defeat in the battle of Galicia and the continuation of the Russian offensive.12 During the Carpathian campaign in the winter of 1914–1915, the regiment mostly scouted and guarded the Carpathian passes until the counteroffensive actions in the spring of 1915. Although the battle for Makivka Mountain (April 28–May 2, 1915) was the USR’s defeat, it became integral to the Ukrainian national historical narrative. Contemporaries characterized the battle for Makivka as “a large Galician Ukrainian attempt to become an active factor in history, to become smiths and creators of their own future.”13 The Legion also took part in victories for the Central Powers’ Gorlice-Tarnów offensive, which resulted in the so-called Great Retreat of the Russian forces and de-occupation of most of Galicia. As for the chronological frames of my research, in October–December 1915, the riflemen were fighting near the Strypa River in the present-day Ternopil oblast.14

The Legion’s Necessities

From the beginning, the Legion depended on the donations of concerned people. In August 1914, the Women’s Organizational Committee provided the USR with 9000 krones from the “Eternal Fund”—a charity foundation established in 1913 for potential “national struggles.”15 Also, a collection campaign began, and, according to Mykola Lazarovych, within a month, people donated a few hundred thousand krones in money, valuables, and goods.16

In November 1915, the UMB described the Legion’s needs. The Board divided them into nine “funds”: organization—financing the recruitment campaign and management, printing proclamations, reports, and letters; support—financing the riflemen’s expenditures (travel expenses, taxes, food, and minor costs), clothing for the retired riflemen in need, “parcels that are sent on the battlefield”; treatment—financing the treatment of ill and injured riflemen; veterans—financial help for veterans in need; disabled—help and fees for disabled; distinctions—issuing commemorative honors and diplomas for every rifleman, cockades and flags; museum—expenses in organizing the USR museum (includes taking photographs); publishing—printing postcards and postal stamps, journal, album, books, and authors’ salary; commemoration—constructing and maintaining graves and monuments of fallen riflemen, and organizing commemorative visits to the graves.17

The Board’s report of donations and expenditures shows the priorities in 1915. From August 31, 1914, to September 1, 1915, the USR Treasury received 22,705 krones of donations through Vienna. The Treasury spent 22,226 krones of this sum: 24% of the expenses were on making photographs, 22%—on organizing the riflemen (presumably, recruitment and training), 7%—on publishing, 2%—on management, and the rest 44%—on “supporting” the riflemen, which most likely meant help for fighting personnel.18 Based on the report, it seems most of the money donated to the Legion was spent on “support.”

The Quantity of Donations in October-December 1915

I divided announcements regarding donations in the Ukrainske Slovo newspaper into three categories: the USR fund (including material help to the riflemen on the battlefield), the Disabled fund, and charity for the hospitals.

The first category covered the Legion’s necessities described above. According to the reports in the Ukrainske Slovo (13 messages), people and institutions had donated about 5057 krones in October–December 191519 (in November 1915, a kilogram of pork cost five krones, the same amount of lard—6 krones and 80 hellers;20 a heller was one-hundredth of the krone). The USR Commissariat in Lviv and the UMB office in Vienna were the institutions that accepted donations; the latter, being the logistics and administrative center of the regiment, was responsible for managing the expenses.

In addition to irregular contributions made by citizens, women’s organizations like the Women’s Committee for Helping Injured Soldiers (Zhinochyi komitet dopomohy ranenym zhovniram, also known as the Ukrainian Women’s Committee) contributed through charity campaigns. For example, on November 19, 1915, the UMB, with the Ukrainian Women’s Committees in Vienna and Lviv, announced the start of the pre-Christmas collection campaign. The campaign aimed to raise money to buy practical things for the battlefield riflemen and to give them on Christmas warm winter clothes and “tiny things that are usually presented for such occasions (cigarettes, chocolate, etc.).”21 In sum, people donated “on the Christmas Tree” (“na yalynku”) or “on Christmas” (“na koliadu”22 ) 1413 krones by December 30, 1915.23 Furthermore, the Women’s Committee began gathering winter clothes already in October 1915: “We accept everything because everything is in need: cloth, wool fabric, shoes, blankets, bedspreads, fur coats, cloaks, capes, scarves, both new and old, different underwear or clothing, either things like galoshes and other rubber products, even if old. First, we ask for even small financial support.”24 In the last days of October, members of the Women’s Committee in Lviv visited people’s houses to collect materials for warm clothes and, at the beginning of November, to fundraise for the same purpose.25

The second category encompasses the Fund of the Disabled Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (Fond Invalidiv Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv). It emerged at the end of September 1915 through physician Osyp Kovshevych’s initiative. He provided the first 200 krones. The importance of founding a separate fund for helping traumatized riflemen was to guarantee the veterans’ well-being upon retirement from service, even though the Austrian government, in Mykhailo Voloshyn’s opinion, would include the Sich Riflemen with the Imperial-Royal Army veterans. However, he also emphasized: “…the soldier of the [Imperial-Royal] Army joined [the army] under compulsion, whereas our Riflemen are volunteers.”26 Apparently, they were not sure about the government’s decisions.

People fundraised approximately 51,109 krones for the Disabled Fund during the studied period.27 Moreover, citizens of Tustanovychi, a town in the Boryslav oil field, collected 50 thousand krones, making up 98% of the sum.28 It was the largest donated sum among all the reports in the Ukrainske Slovo from October to December 1915. According to ecclesiastical statistics, in 1913, there were 2846 Greek Catholics in Tustanovychi, and 1360 of them worked at local oil companies.29 The newspaper article’s author described Tustanovychi as “the sole Ukrainian village in the Boryslav oil field that oil industrialists did not exploit and has not disappeared from the Earth’s face as a Ukrainian community. Apart from the material prosperity, Tustanovychi leads in the enlightening and economic life of Drohobych district.”30

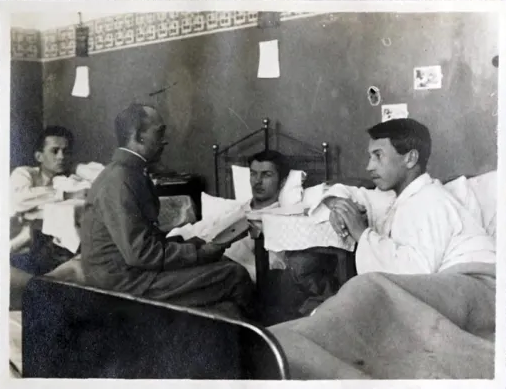

The third category covered the needs of military hospitals in Lviv, more precisely, the hospital of the Ukrainian Samaritan Help (Ukrainska Samarytanska Pomich, USH) and the USR Shelter (Pryiut USS). The USH was another women’s organization that appeared after the Austrian recapture of Lviv in June 1915, and its main aim was to support the military hospital the organization founded. It was not a “national” hospital, as there were soldiers of different nationalities among the patients, but the personnel consisted exclusively of Ukrainian women.31 The reports concerning the donations to the USH were usually published in the Ukrainske Slovo under the title: “The Golden Ukrainian Heart.” The sum of donations from October–December 1915 was equal to 752 krones;32 a priest Markevych also donated 11 German pfennigs and 40 Russian kopeks.33 In addition, the “Samaritans” kept a hospital library, so they asked people to send them “Ukrainian journals that had been read as well as books with approachable content.”34

Another USH initiative was a “Christmas Tree” for the Ukrainian soldiers in Lviv hospitals. According to their announcement before the organizational meeting on December 1, 1915, around 600 Ukrainian soldiers were recovering in Lviv hospitals. “The Ukrainian community of our capital [Lviv] should not allow those who risked their lives in a fight with the enemy to feel left out here,” stated the announcement. The USH aimed to arrange Christmas Eve for injured Ukrainian soldiers on January 6; hence, the committee of the USH encouraged Lviv citizens, especially women, to contribute money or to participate in organizing.35 The community responded actively, as in another organizational announcement from December 11, the USH reported that some volunteers were turned away as there were no places.36 The USH received contributions in money and goods (festive sweets).37 In total, the Ukrainske Slovo reported 514 krones as donations “for the Christmas Tree” in hospitals.38

The USR Shelter was a hospital dedicated only to the Sich Riflemen and was also under the care of the USH. It was located in the Greek Catholic cantors’ school building near the “People’s Hospital,” both funded by Greek Catholic metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi. Doctor Bronislav Ovcharskyi, the USH member, cured wounded riflemen here for free. On average, around 30 patients could be treated at once. This institution was established in August 1915.39

The Shelter depended on benefactors as well. A wife of some professor, named in the article “K. L-ova,” donated to the USR a large amount of underwear in 1914, which was later handed over to the Shelter; in 1915, she also donated 900 krones and bought cloaks, bandages, and cotton wool. Professor Vasyl Shchurat, “Prosvita” director Antin Hapiak, and editor-in-chief of the Dilo newspaper Vasyl Paneiko made their donations in books for the hospital library.39 According to the reports in the Ukrainske Slovo, the Shelter received 779 krones in October-December 1915.40

The Ways to Raise Donations

The reports posted in the Ukrainske Slovo do not represent the whole fundraising campaign for the Legion, because these reports covered only donations that had been coming to Lviv. The donations’ geography mainly covered Eastern Galicia’s whole territory (with exclusions in mountain regions and frontline areas). However, the largest portion was from the countryside close to Lviv, which can be explained by physical proximity. Also, a few reports considered the donations from the Lemko Region. The contributions made outside Eastern Galicia, for example, in the Western Crownland’s part, Vienna, or Northern America, are a place for further research.

Ukrainske Slovo reported on the money donated to the USR Commissariat in Lviv, as well as the contributions made through the newspaper’s editorial office. The majority were individual contributions and fundraising from communities and parishes. Mostly, people donated from one to two krones, sometimes five or ten; there were some larger contributions, but they did not predominate.

The UMB encouraged Ukrainians to fundraise for the USR Legion “at every opportunity, in every circle, in every area.”17 Ukrainske Slovo depicted different occasions. The newspaper reported on Volodymyra Senytsia, “a beautiful Ukrainian girl,” who raised 22 krones in Zapytiv village (Lviv district) for the Disabled Fund on the day of birth of Francis Joseph I: August 18, 1915.41 On December 2, there was a ceremonial consecration of a cross monument dedicated to Francis Joseph’s accession to the throne in Sokolivka village (Kosiv district). The participants, including guests from neighboring villages, donated 81 krones to the USR’s “Christmas Tree.”42 A special occasion was a banquet celebrating USR colonel Hryhorii Kossak’s birthday in Lviv. The guests—intelligentsia, artists, and politicians (about 60 people)—contributed to the “Christmas Tree” 268 krones.43

Another way to donate, besides direct monetary contribution, was by buying brochures, post cards, or badges.17 For instance, the USR Commissariat in Lviv had been selling the “military distinctions in national [blue and yellow] colors with ‘U. S. R. 1914’ inscription.”44 A single badge cost 20 hellers, and the Commissariat handed over the profits from selling to the Disabled Fund.45 Likewise, the Ukrainian Samaritan Help sold charity stamps.46

There were a few ways to make an individual contribution. On the one hand, a person could transfer money to the address of the USR Commissariat in Lviv or the UMB in Vienna. Ukrainske Slovo also reported the donations made through the newspaper’s editorial office. In addition, the Disabled Fund had an account with the Mortgage Bank of Lviv.47

The parish priests played an important role in fundraising, representing their flock, and being trusted persons or intermediates between the people and institutions. According to scholars Vasyl Rasevych and Andriy Zayarnyuk, the Greek Catholic clergy during the war was a social group that influenced and had direct contact with Galician Ukrainian peasantry and was closely associated with Ukrainian identity as a? cultural phenomenon.48 A local priest was trusted to collect money in 25 parishes out of 44 (57%). Even when priests were not the ones to whom people passed their cash, they helped as organizers. For example, in Velyki Pidlisky village (Lviv district), the community head, Yakiv Zvarych, and members of the local church brotherhood were gathering money, but the initiator was parish priest Ivan Pelekh.49

Furthermore, the Church was the institution that had the most comprehensive network of parishes and a well-organized hierarchy. Thus, I suppose the appeal to the Church was inevitable, especially in the hard-to-reach mountain regions, which the network of secular national institutions would not cover. The people of Holovetsko, Hrabovets, and Rykiv villages in the mountainous Skole district donated 166 krones to the Legion’s “Christmas Tree.” The report did not mention the person who led the fundraising or organizing.50 However, it was most likely the local priest, because Hrabovets and Rykiv were the chapels of ease for the Theophany parish church in Holovetsko; the inhabitants of these three villages were the flock of a single priest.51 A clergy member of a higher rank could also be the organizer of the fundraising as in the Khodoriv deanery. On December 5, 11, and 12, 1915, Ukrainske Slovo reported on the contributions made in Zalistsi, Zhyrava, and Bohorodchytsi villages, where people gave their donations to the dean of Khodoriv, Ivan Vynnytskyi, who in turn transferred this money to Lviv.52

Thus, the Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen depended on the benefactors’ donations, which is why the Ukrainian Military Board, in cooperation with charity institutions, announced fundraising campaigns. The urgent wartime needs did not limit the Legion’s necessities, and it also included support for disabled veterans, military hospitals, and prospective cultural and commemorative aims. The periodicals were the instruments for spreading information about the launched campaigns, and Ukrainske Slovo was one of them. By publishing the reports of contributions, the newspaper’s editors informed people about the charity funds’ incomes and also, which is more significant, motivated potential benefactors to donate by showing “an example worthy of following.”

Bibliography

Baidak, Mariana. “Zhinka v umovakh viiny u svitli povsiakdennykh praktyk (na materialakh Halychyny 1914–1921 rr.)” [“Woman in War Circumstances in light of everyday practiсes (on Galician materials, 1914–1921)”]. Candidate’s of Historical Sciences (Ph. D.) dissertation, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, 2018.

Berest, Ihor. “Represyvni aktsii shchodo naselennia Skhidnoi Halychyny v roky Pershoi svitivoi viiny” [“Repressions of Eastern Galician People during the First World War”]. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Universytetu “Lvivska Politechnika,” Derzhava i Armiia, no. 584 (2007): 52–57.

Knyhynycka, Oksana. “‘Zhinochyi orhanizatsiinyi komitet’ v Halychyni naperedodni Pershoi svitovoi viiny” [“Women’s Organizational Committee in Galicia on the Eve of the First World War”]. Visnyk of the Lviv University. Series History, special issue (2017): 433–42.

Lazarovych, Mykola. Legion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv: formuvannia, ideia, borotba [Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen: formation, idea, struggle]. Ternopil: Dzhura, 2005.

Lytvyn, Mykola. “Lehion Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv: viiskove navchannia, vykhovannia, boiovyi shliakh” [“The Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen: Military Training, Education, Battle Path”]. In Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], 1: 159–79. Kyiv: Klio, 2014.

M., Ya. “Pryiut dlia neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv u Lvovi” [“Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen in Lviv”]. Ukrainske Slovo, October 19, 1915.

Ozarkevych, [Yevhen]. “Opovistky. Na Pryiut Uk. Sich. Striltsiv” [“Announcements. For the Shelter of Uk[rainian]. Sich Riflemen”]. Ukrainske Slovo, November 30, 1915.

Peredyrii, Valentyna. “Ukrainske Slovo” [“The Ukrainian Word”]. In Ukrainska presa v Ukraini i sviti XIX–XX st.: istoryko-bibliohrafichne doslidzennia [Ukrainian Press in Ukraine and Around the World in 19th–20th Centuries: Historical-Bibliographical Study], 4: 1911–1916 rr.: 404–11. Lviv: NAS of Ukraine, V. Stefanyk National Scientific Library of Lviv, 2014.

Reient, Oleksandr. “Persha svitova viina i politychni syly ukrainstva” [“The First World War and Ukrainian Political Powers”]. In Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], 1: 302–9. Kyiv: Klio, 2014.

Reient, Oleksandr, and Bohdan Yanyshyn. “Persha svitova viina v ukrainskii istoriohrafii” [“World War I in the Ukrainian Historiography”]. In Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], 1: 17–60. Kyiv: Klio, 2014.

Shematyzm vseho hreko-katolytskoho Klira zluchenykh Eparkhii Peremyskoi, Sambirskoi i Sianickoi na rik 1914 [Schematismus of the Whole Greek Catholic Clergy of the United Eparchies of Peremyshl, Sambir and Sianik on Year 1914]. Peremyshl, n.d.

Shematyzm Vseho Klira Hreko-Katolytskoi Mytropolychoi Arkieparkhii na rik 1914 [Schematismus of the Whole Clergy of the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Archeparchy for Year 1914]. Vol. 70. Lviv, 1913.

Soldatenko, Valerii. “‘Ukrainska Tema’ v Politytsi Derzhav Avstro-Nimetskoho Bloku i Antanty” [“‘Ukrainian Theme’ in Politics of the Austro-German Bloс and the Entente States”]. In Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], 1: 80–109. Kyiv: Klio, 2014.

Tryliovskyi, Kyrylo, and Volodymyr Temnytskyi. “Ukrainskyi narid Ukrainskym Sichovym Striltsiam na koliadu!” [“Ukrainian People for Ukrainian Sich Riflemen on Koliada!”]. Ukrainske Slovo, November 25, 1915.

Wendland, Anna Veronika. Rusofily Halychyny. Ukrainski konservatory mizh Avstriieiu Ta Rosiieiu, 1848–1915 [Galician Rusophiles. Ukrainian Conservatives between Austria and Russia]. Translated by Khrystyna Nazarkevych. Lviv: Litopys, 2015.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Dlia Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv [For the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen].” November 24, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Fond Invalidiv Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Stritsiv” [“Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’s Fund of Disabled”]. September 30, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Na Pryiut dlia neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv, Ukr. Samar. Pomochy” [To the Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, Ukr[ainian]. Samar[itan]. Help”]. October 15, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Dar sniatynskoho povitu Ukrainskym Sichovym Striltsiam” [“Latest. Sniatyn District’s Gift to the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen”]. December 15, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Hostyna polkovnyka Kossaka” [“Latest. Collonel’s Kossak Banquet”]. December 2, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Kniazhyi dar” [“Latest. Noble Gift”]. November 25, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Maksymalni tsiny na veprovynu” [“Latest. Maximal Pork Prices”]. November 28, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Na yalynku dlia U. S. S.” [“Latest. For a Christmas Tree for U. S. R.”]. December 21, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Podumaimo i pro nashykh Sichovykh Striltsiv!” [“Latest. Let’s Think About Our Sich Riflemen Too!”]. October 17, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Prymir hidnyi do naslidovannia” [“Latest. An Example Worthy to Follow”]. October 5, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Prymir hidnyi naslidovannia” [“Latest. An Example Worth to Follow”]. December 16, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Shchedryi dar” [“Latest. A Generous Gift”]. December 17, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Sviato na seli” [“Latest. Holiday in a Village”]. December 12, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Ukrainske, harne divchatko Volodymyra Senytsia” [“Latest. Beautiful Ukrainian Girl Volodymyra Senytsia”]. October 17, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. Ukrainski hromady — svoim Sichovym Striltsiam” [“Latest. Ukrainian Communities to Their Sich Riflemen”]. December 19, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Novynky. V Komisariiati Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Latest. In Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Commissariat”]. October 5, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Do ukrainskoi suspilnosty u Lvovi!” [“Announcements. To Ukrainian Community in Lviv!”]. December 1, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Komandant stanytsi U. S. S.” [“Announcements. Commandant of U. S. R. Hearth”]. December 9, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Komitet dlia nesennia pomochy” [“Announcements. The Relief Committee”]. October 22, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Komitet dlia nesennia pomochy” [“Announcements. The Relief Committee”]. October 25, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Podumaimo i pro nashykh Sichovykh Striltsiv!” [“Announcements. Let’s Think About Our Sich Riflemen Too!”]. October 22, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Podumaimo i pro nashykh Sichovykh Striltsiv!” [“Announcements. Let’s Think About Our Sich Riflemen Too!”]. October 28, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Ukr. Sam. Pomich” [“Announcements. Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”]. December 16, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Ukr. Sam. Pomich” [“Announcements. Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”]. December 19, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Ukr. Sam. Pomich” [“Announcements. Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”]. December 27, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. V Komisariiati Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Announcements. In Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Commissariat”]. October 10, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. V Komisariiati Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Announcements. In Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Commissariat”]. October 14, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Vid Ukr. Sam. Pomochy” [“Announcements. From Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”]. December 11, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Vid Ukr. Sam. Pomochy” [“Announcements. From Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”] December 28, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Vid ‘Ukrainskoi Samarytanskoi Pomochy’” [“Announcements. From Ukrainian Samaritan Help”]. October 18, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Zariad ‘Ukrainskoi Samarytanskoi Pomochy’” [“Announcements. Ukrainian Samaritan Help’s Management”]. November 21, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Opovistky. Zariad ‘Ukrainskoi Samarytanskoi Pomochy’” [“Announcements. Ukrainian Samaritan Help’s Management”]. December 3, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Skarb Ukr. Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Ukr[ainian] Sich Riflemen’s Treasury”]. November 21, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “V Komisariiati U. S. S. u Lvovi” [“In the U. S. R. Commissariat in Lviv”]. October 7, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy” [“Donations”]. November 28, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy” [“Donations”]. December 8, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy” [“Donations”]. December 12, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy” [“Donations”]. December 23, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy” [“Donations”]. December 25, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy” [“Donations”]. December 30, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy. Na Invalidiv U. S. S.” [“Donations. For the Disabled U. S. R.”]. November 5, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy. Na koliadu dlia Ukr. Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Donations. For Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’s Koliada”]. December 10, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy. Na Pryiut neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv (Lviv, vul. Petra Skarhy 3)” [“Donations. For the Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (Lviv, Piotr Skarga Street 3)”]. November 14, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy. Na ‘Ukrainsku Samarytansku Pomich’” [“Donations. On the Ukrainian Samaritan Help”]. November 21, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy. Zolote Ukrainske Sertse” [“Donations. Golden Ukrainian Heart”]. December 5, 1915.

Ukrainske Slovo. “Zhertvy. Zolote Ukrainske Sertse” [“Donations. Golden Ukrainian Heart”]. December 11, 1915.

- “Ukraintsi maizhe vdvichi menshe zadonatyly u 2023 rotsi nizh na pochatku velykoi viiny” [“Ukrainians Donated Almost Half as Much in 2023 as at the Beginning of the Great War”], Opendatabot, February 19, 2024, https://opendatabot.ua/analytics/donation-2023 [↩]

- Valentyna Peredyrii, “Ukrainske Slovo” [“The Ukrainian Word”], in Ukrainska presa v Ukraini i sviti XIX–XX st.: istoryko-bibliohrafichne doslidzennia [Ukrainian Press in Ukraine and Around the World in 19th–20th Centuries: Historical-Bibliographical Study], vol. 4: 1911–1916 rr. (Lviv: NAS of Ukraine, V. Stefanyk National Scientific Library of Lviv, 2014), 404–11. [↩]

- Mykola Lazarovych, Legion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv: formuvannia, ideia, borotba [Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen: formation, idea, struggle] (Ternopil: Dzhura, 2005), 72. [↩]

- Valerii Soldatenko, “‘Ukrainska tema’ v politytsi derzhav avstro-nimetskoho bloku i Antanty” [“‘Ukrainian Theme’ in the Politics of the Austro-German Bloс and the Entente States”], in Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], vol. 1, 2 vols (Kyiv: Klio, 2014), 84. [↩]

- Oleksandr Reient, “Persha svitova viina i politychni syly ukrainstva” [“The First World War and Ukrainian Political Powers”], in Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], vol. 1, 2 vols (Kyiv: Klio, 2014), 303. [↩]

- Reient, “Persha svitova viina i politychni syly ukrainstva,” 303. [↩]

- “Manifest Holovnoi Ukrainskoi Rady” [“The Supreme Ukrainian Council Manifest”]. Vistnyk Soiuza Vyzvolennia Ukrainy [Union for the Liberation of Ukraine Herald] I, no. 2 (October 27, 1914): 8. [↩]

- Reient, ‘Persha svitova viina i politychni syly ukrainstva,’ 303. [↩]

- Anna Veronika Wendland, Rusofily Halychyny. Ukrainski konservatory mizh Avstriieiu ta Rosiieiu, 1848–1915 [Galician Rusophiles. Ukrainian Conservatives between Austria and Russia], trans. Khrystyna Nazarkevych (Lviv: Litopys, 2015), 558. [↩]

- Lazarovych, Legion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv, 75-76. [↩]

- Lazarovych, Legion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv, 81; Mykola Lytvyn, ‘Lehion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv: viiskove navchannia, vykhovannia, boiovyi shliakh’ [‘The Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen: Military Training, Education, Battle Path’], в Velyka viina 1914–1918 rr. i Ukraina [Great War 1914–1918 and Ukraine], vol. 1, 2 vols. (Kyiv: Klio, 2014), 159. [↩]

- Lytvyn, 161. [↩]

- Lytvyn, 163-164. [↩]

- Lytvyn, 165-168. [↩]

- Oksana Knyhynycka, ‘“Zhinochyi orhanizatsiinyi komitet” v Halychyni naperedodni Pershoi svitovoi viiny’ [‘Women’s Organizational Committee in Galicia on the Eve of the First World War’], Visnyk of the Lviv University. Series History, Special issue (2017): 440; Lazarovych, Legion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv, 81. [↩]

- Lazarovych, Legion Ukrainskykh sichovykh striltsiv, 81. [↩]

- “Dlia Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“For the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 24, 1915. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- “Skarb Ukr. Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Ukr[ainian]. Sich Riflemen’s Treasury”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 21, 1915. [↩]

- “V Komisariiati U. S. S. u Lvovi” [“In the U. S. R. Commissariat in Lviv”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 7, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 8, 1915; “Opovistky. Komandant stanytsi U. S. S.” [“Announcements. Commandant of the U. S. R. Hearth”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 9, 1915; “Zhertvy. Na koliadu dlia Ukr. Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Donations. For Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’s Koliada”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 10, 1915; “Novynky. Sviato na seli” [“Latest. Holiday in a Village”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915; “Novynky. Dar sniatynskoho povitu Ukrainskym Sichovym Striltsiam” [“Latest. Sniatyn District’s Gift to the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 15, 1915; “Novynky. prymir hidnyi naslidovannia” [“Latest. An Example Worth to Follow”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 16, 1915; “Novynky. Shchedryi dar” [“Latest. A Generous Gift”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 17, 1915; “Novynky. Ukrainski hromady — svoim Sichovym Striltsiam” [“Latest. Ukrainian Communities to Their Sich Riflemen”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 19, 1915; “Novynky. Na yalynku dlia U. S. S.” [“Latest. For a Christmas Tree for U. S. R.”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 21, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 23, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 25, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 30, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Maksymalni tsiny na veprovynu” [“Latest. Maximal Pork Prices”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 28, 1915. [↩]

- Kyrylo Tryliovskyi and Volodymyr Temnytskyi, “Ukrainskyi narid Ukrainskym Sichovym Striltsiam na koliadu!” [“Ukrainian People for Ukrainian Sich Riflemen on Koliada!”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 25, 1915. [↩]

- In Ukrainian, the word “koliada” has two meanings: carols sang on Christmas and the period of the Christmas holidays. It makes it complicated to translate the phrase in English as it could mean, on the one hand, the simulation of tradition to gift sweets or/and money to the boy singing carols, on the other, preparing presents, where Christmas is only an occasion. I believe translating “na koliadu” as “on Christmas” mainly transmits the semantics of the phrase and reflects the initiative to give the riflemen useful things, the feeling of home and the family atmosphere. [↩]

- “Opovistky. Komandant Stanytsi U. S. S.” [“Announcements. Commandant of U. S. R. Hearth”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 9, 1915; “Zhertvy. Na koliadu dlia Ukr. Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Donations. For Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’s Koliada”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 10, 1915; “Novynky. Sviato na seli” [“Latest. Holiday in a Village”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915; “Novynky. Prymir hidnyi naslidovannia” [“Latest. An Example Worth to Follow”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 16, 1915; “Novynky. Shchedryi dar” [“Latest. A Generous Gift”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 17, 1915; “Novynky. Ukrainski hromady — svoim Sichovym Striltsiam” [“Latest. Ukrainian Communities to Their Sich Riflemen”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 19, 1915; “Novynky. Na yalynku dlia U. S. S.” [“Latest. For a Christmas Tree for U. S. R.”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 21, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 25, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 30, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Podumaimo i pro nashykh Sichovykh Striltsiv!” [“Latest. Let’s Think About Our Sich Riflemen Too!”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 17, 1915; “Opovistky. Podumaimo i pro nashykh Sichovykh Striltsiv!”, Ukrainske Slovo, October 22, 1915; “Opovistky. Podumaimo i pro nashykh Sichovykh Striltsiv!”, Ukrainske Slovo, October 28, 1915. [↩]

- “Opovistky. Komitet dlia nesennia pomochy” [“Announcements. The Relief Committee”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 22, 1915; “Opovistky. Komitet dlia nesennia pomochy,” Ukrainske Slovo, October 25, 1915. [↩]

- “Fond Invalidiv Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Stritsiv” [“Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’s Fund of Disabled”], Ukrainske Slovo, September 30, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Prymir hidnyi do naslidovannia” [“Latest. An Example Worthy to Follow”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 5, 1915; “Zhertvy. Na Invalidiv U. S. S.” [“Donations. For the Disabled U. S. R.”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 5, 1915; “Novynky. Ukrainske, harne divchatko Volodymyra Senytsia” [“Latest. Beautiful Ukrainian Girl Volodymyra Senytsia”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 17, 1915; “Novynky. Kniazhyi dar” [“Latest. Noble Gift”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 25, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 28, 1915; “Zhertvy. Zolote ukrainske sertse” [“Donations. Golden Ukrainian Heart”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 5, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 25, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 23, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 30, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Kniazhyi dar” [“Latest. Noble Gift”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 25, 1915. [↩]

- Shematyzm vseho hreko-katolytskoho Klira zluchenykh Eparkhii Peremyskoi, Sambirskoi i Sianickoi na rik 1914 [Schematismus of the Whole Greek Catholic Clergy of the United Eparchies of Peremyshl, Sambir and Sianik on Year 1914] (Peremyshl, n.d.), 93. [↩]

- “Novynky. Kniazhyi dar”[“Latest. Noble Gift”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 25, 1915. [↩]

- Mariana Baidak, “Zhinka v umovakh viiny u svitli povsiakdennykh praktyk (na materialakh Halychyny 1914–1921 rr.)” [“Woman in War Circumstances in light of everyday practices (on Galician materials, 1914–1921)”] (Candidate’s of Historical Sciences (Ph. D.) dissertation, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, 2018), 83. [↩]

- “Na Pryiut dlia neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv, Ukr. Samar. Pomochy” [“To the Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, Ukr[ainian]. Samar[itan]. Help”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 15, 1915; “Zhertvy. Na ‘Ukrainsku Samarytansku Pomich’” [“Donations. On the Ukrainian Samaritan Help”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 21, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 28, 1915; “Zhertvy. Zolote Ukrainske Sertse” [“Donations. Golden Ukrainian Heart”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 11, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 25, 1915. [↩]

- “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915. [↩]

- “Opovistky. Zariad ‘Ukrainskoi Samarytanskoi Pomochy’” [“Announcements. Ukrainian Samaritan Help’s Management”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 21, 1915; “Opovistky. Zariad ‘Ukrainskoi Samarytanskoi Pomochy’” [“Announcements. Ukrainian Samaritan Help’s Management”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 3, 1915. [↩]

- “Opovistky. Do Ukrainskoi Suspilnosty u Lvovi!” [“Announcements. To Ukrainian Community in Lviv!”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 1, 1915. [↩]

- “Opovistky. Vid Ukr. Sam. Pomochy” [“Announcements. From Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 11, 1915. [↩]

- “Opovistky. Ukr. Sam. Pomich” [“Announcements. Ukr[ainian]. Sam[aritan]. Help”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 16, 1915. [↩]

- “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 25, 1915. [↩]

- Ya. M., “Pryiut dlia neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv u Lvovi” [“Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen in Lviv”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 19, 1915. [↩] [↩]

- “Zhertvy. Na Pryiut neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv (Lviv, vul. Petra Skarhy 3)” [“Donations. For the Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (Lviv, Piotr Skarga Street 3)”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 14, 1915; [Yevhen] Ozarkevych, “Opovistky. Na Pryiut Uk. Sich. Striltsiv” [“Announcements. For the Shelter of Uk[rainian]. Sich Riflemen”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 30, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 30, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Ukrainske, harne divchatko Volodymyra Senytsia” [“Latest. Beautiful Ukrainian Girl Volodymyra Senytsia”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 17, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Sviato na seli” [“Latest. Holiday in a Village”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Hostyna Polkovnyka Kossaka” [“Latest. Collonel’s Kossak Banquet”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 2, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. V Komisariiati Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Latest. In Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Commissariat”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 5, 1915; “Opovistky. V Komisariiati Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Announcements. In Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Commissariat”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 10, 1915; “Opovistky. V Komisariiati Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv” [“Announcements. In Ukrainian Sich Riflemen Commissariat”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 14, 1915. [↩]

- Ibid [↩]

- “Na Pryiut dlia neduzhykh Ukrainskykh Sichovykh Striltsiv, Ukr. Samar. Pomochy” [“To the Shelter of Ill Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, Ukr[ainian]. Samar[itan]. Help”], Ukrainske Slovo, October 15, 1915. [↩]

- “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, November 28, 1915. [↩]

- Andriy Zayarnyuk and Vasyl Rasevych, “Halytske hreko-katolytske dukhovenstvo u Pershii svitovii viini: politychni, kulturni i sotsiialni aspekty” [“Galician Greek Catholic Clergy in the First World War: Political, Cultural and Social Aspects”], Kovcheh VI (2012): 160. [↩]

- “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 23, 1915. [↩]

- “Novynky. Ukrainski hromady — svoim sichovym Striltsiam” [“Latest. Ukrainian Communities to Their Sich Riflemen”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 19, 1915. [↩]

- Shematyzm Vseho Klira Hreko-Katolytskoi Mytropolychoi Arkieparkhii na rik 1914 [Schematismus of the Whole Clergy of the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Archeparchy for Year 1914], vol. 70 (Lviv, 1913), 377. [↩]

- “Zhertvy. Zolote Ukrainske Sertse” [“Donations. Golden Ukrainian Heart”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 5, 1915; “Zhertvy. Zolote Ukrainske Sertse” [“Donations. Golden Ukrainian Heart”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 11, 1915; “Zhertvy” [“Donations”], Ukrainske Slovo, December 12, 1915. [↩]