Taras Shevchenko is a symbol of Ukrainian national identity who transcended his own lifetime. The myth of Shevchenko, the national hero poet, became deeply intertwined with the socio-political currents and ideological movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. This article explores the evolution of the Shevchenko myth within the urban context of Katerynoslav (modern Dnipro), a major polyethnic industrial city, examining how his legacy was adopted, adapted, and contested within this dynamic public sphere.

The research was developed during the “Rethinking Ukrainian Studies in a Global Context” course at the Invisible University for Ukraine, guided by Ostap Sereda (UCU and CEU), and prepared for publication in collaboration with Nadiia Chervinska (CEU). The research was supported by the Open Society University Network (OSUN) and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

Taras Shevchenko is traditionally regarded as one of the fundamental figures in the formulation of Ukrainian national identity. Like any idea, the concept of a national hero develops within a certain socio and cultural environment; Shevchenko very quickly became the hero of his own myth of Ukraine, later turning into a completely autonomous myth of the author himself.1

In retrospect, today we can say that even during Shevchenko’s lifetime, his myth was embedded in the socio-political currents and discourses of diverse ideological “isms”—socialism, nationalism, internationalism, monarchism, and revolutionary democracy.2 By the end of the 19th century, the national or Ukrainophile discourse surrounding Shevchenko’s image had already begun to spread, portraying him as a serf-slave, a martyr who managed to become the voice of the enslaved Ukrainian folk and was affectionately referred to as “Father Taras.”3

This discourse was consolidated through the sacralization of the poet, the growth of a cult, and the creation of a tradition. In this context, tradition means practices of a ritual or symbolic nature, which are conditioned directly or indirectly by accepted rules, and instill values and ethics through repetition. There is an implicit connection with the past.4 In this case, the myth itself is a ritual in verbal form—a closed semiotic system with a set of universal symbols, which perform the ritual’s regulatory function.5 Shevchenko’s myth of Ukraine, embracing the peasant and the Cossack worlds, laid the foundation for understanding “Ukrainianness” in the categories of nationality.

The discourse about nationalism strives to create cultural awareness and rhetoric that aligns with society’s aspirations in terms of nation and national identity. It attempts to develop fundamental models of language, thought, and behavior patterns that reflect and reinforce national narratives.6 National identity and national self-identification emerge through the assimilation of this discourse through myth and tradition.7

This research aims to understand how the national myth of Shevchenko penetrated the urban public sphere of Katerynoslav—the largest polyethnic industrial Ukrainian city at the end of the 19th century. It considers the impact of modernization on the idea of nationalism, proposed in a functionalist version by Ernest Gellner, that gives the city a decisive role in the creation of a nation. The city itself is the institutional framework in which language, behavior patterns, and cultural models are formed, and social ties and infrastructure for communication are established.8

To trace and analyze the presence of Shevchenko’s myth, the actors of public discourse will be identified using institutional and personological approaches. The institutional dimension is represented by the numerous public institutions, communities, and the press, which emerged strongly in the city at the peak of its demographic and economic development at the end of the 19th century. The local periodical press and magazines, which united local intellectuals and significantly shaped the discourse among readers, are analyzed in the first part of the article. In the second part of the study, the case-study method is used to analyze the 100th-anniversary celebrations of Taras Shevchenko’s birth, focusing on the interactions between the various institutions and authorities involved.

The study explores the contributions of individuals such as ethnographer Ivan Manzhura and historians Dmytro Yavornytskyi and Dmytro Doroshenko. Each of them presents Katerynoslav as a cultural and intellectual center formed largely by the influx of key people from other intellectual centers, primarily from Kharkiv, St. Petersburg, and Kyiv.9

Shevchenko on Steppe’s Pages

One of Katerynoslav’s first key periodicals was the literary and public weekly Steppe, which was published during 1885–1886 by O. Egorov (1850–1903), a graduate of the Faculty of Law of Kharkiv Imperial University. Steppe’s office was located in S. Egorova’s Bookstore on Prospekt—one of the oldest libraries in the city, where the active creative intelligentsia often gathered during the 1870/1880s, later becoming the basis of the editorial team. This group included: folklorist Hryhorii Zalyubovsky (1836–1898), collector of antiques Yakiv Novitskyi (1847–1925), journalist Mykola Bykov (1857–1917), botanic geographer Ivan Akinfiev (1851–1919) and folklorist poet Ivan Manzhura (1851–1893).

A researcher of local literature, N. Vasylenko called them “Steppe Parnassus.” The metaphor is a reference to Mount Parnassus, the mythical home of the Muses, metonymically labelling the community of poets and writers. Here, metaphorically, was a lone, unlikely pinnacle of cultural inspiration and aspiration in the midst of the provincial city.

The release of Steppe took place during the renovation of Shevchenko’s grave in Kaniv (1884) and its transformation by Ukrainophiles into a center of the Shevchenko cult.10 Around the same time, the well-known historical and archeographic community magazine Kievskaya Starina was published in Kyiv, becoming from the start a platform for collecting and publishing Shevchenko’s heritage.11 Moreover, for two decades regular memorable evenings were taking place in Lviv and St. Petersburg.12

Steppe’s chronicle reflected two things quite accurately. Firstly, it demonstrated that the public discourse in the intellectual urban space around Shevchenko’s heritage was initially shaped by a group of narodnytska, an ideological direction oriented towards the practices of Ukrainophiles. This is emphasized in the article and poem by I. Manzhura, published in the magazine on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Shevchenko’s death. In his article, Manzhura spotlights the connection of Shevchenko with the “folk,” by which he primarily meant the peasantry: “The appearance of Taras Grigorievich on the gloomy background of serf Ukraine is far from an accidental phenomenon. In his face, all the destitute Little Russian peasantry merged all their best spiritual strength and chose him as the singer of their age-old grief.”13 The narodnytskyi myth of Shevchenko, which foregrounds the role of a poet-martyr, a peasant serf who gave his life to fight against an unjust social system, is even more clearly manifested in the invective poem-message, metonymically addressed to Ukraine: “…buried and mourned her Martyr Son. When she was burying him, she sincerely swore she would never forget him but did not manage to arrange the cross for him at this time… This is how his honest Mother [Motherland] loves the memory of him!” ((Vasylenko N. Litopys literaturno-mystetskykh podii ta sviat pamiati Tarasa Shevchenka v Katerynoslavi // Shevchenkiana Prydniprovia… P. 128.))

The quoted lines of Manzhura also suggest that the Ukrainophile reception of Shevchenko seeped into Katerynoslav’s cultural environment. This opinion is underlined by the January issue of Steppe of the same year, which contains an advertisement for the new edition of Shevchenko’s Haidamaks with a foreword by D. Yavornytskyi. Emphasizing the literary merits of the publication, D. Yavornytskyi also stresses its symbolic value as “the imperishable wreath of the great Father Taras.” The publication of Haidamaks also served as proof that the society has matured to the awareness of the need to honor the memory of its teachers—its “apostles of truth.”14

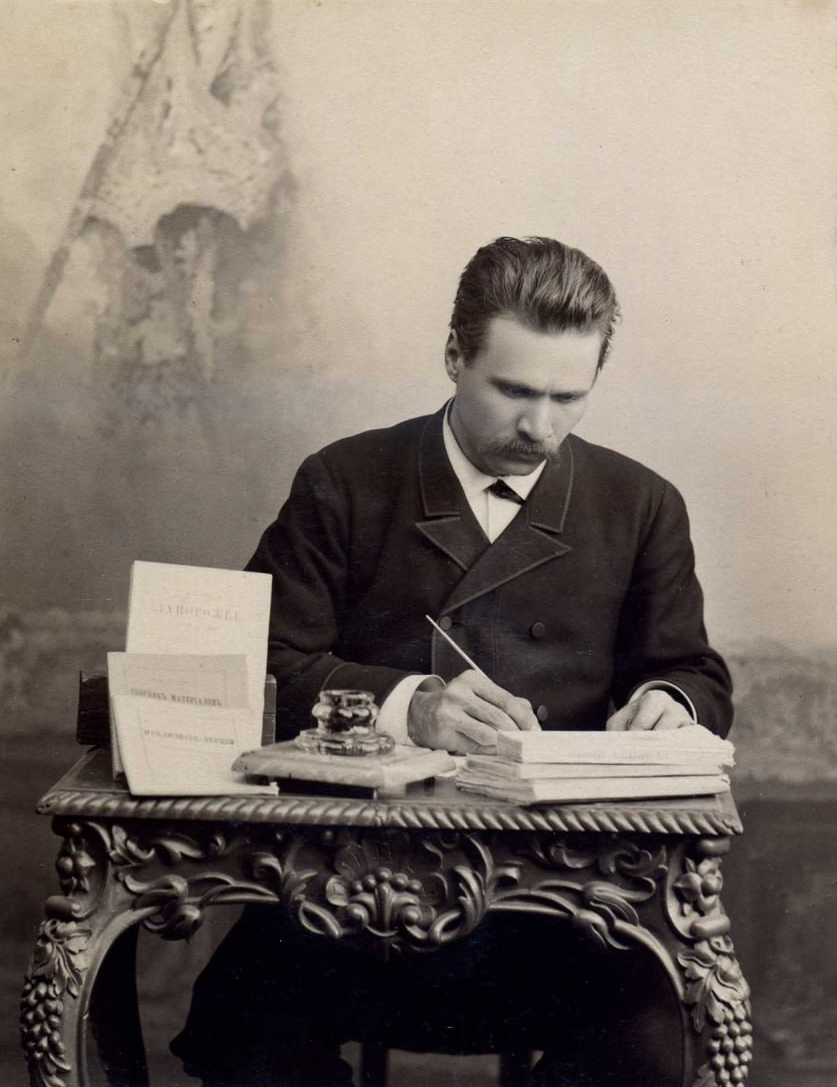

Dmytro Yavornytskyi, Cossack historian, director of the historical museum in Katerynoslav 1902-1933

Yet the absence of effective practices of public veneration of Shevchenko in the middle 1880s—for example, memorial services or vespers—shows the lack of public consensus regarding Shevchenko’s identity in the eyes of local patriots. This is also evidenced by the position of the editor of Steppe O. Egorov, who renounced Ukrainophilstvo in every possible way.15

In 1887, on the eve of Katerynoslav’s centenary, the rapidly growing city was actively searching for its urban identity, in which the myth of Ukraine’s “rural poet” did not fit so easily. The ambiguity in the 1880s was compounded by the story of the city’s founding in 1787 by Empress Ekaterina II, who predicted a great future for the new southern capital of the empire.16 Within the framework of the story, the economic prosperity of the city was perceived as a late realization of 18th-century ideas, which were only postponed due to several unfavorable circumstances.17

Public Actors and the Shevchenko Discourse at the Beginning of the 20th Century

The first public readings of Shevchenko’s poems took place only at the beginning of the 20th century. In April 1902, a news chronicle of the Kievskaya Staryna magazine included a notice about the organization of a commemorative evening for Shevchenko in Katerynoslav.18

The initiator of readings was one of the first popular educational institutions of the city—the Commission of People’s Readings organized in 1883. The commission supported the organization of public literary and musical evenings, folk lectures and commemorative events, and the activities of an amateur choir. In 1896, with funds collected by the common public and local authorities, the Commission built the Auditorium of People’s Readings—its own house, with a lecture hall and theater stage, accessible to everyone, not just the privileged classes.

The organizers showcased a relatively neutral, non-controversial part of Shevchenko’s poems, which mainly touched on the idyllic world of the village (Sadok vyshnevyi kolo khaty), social injustice (I tudy, i vsiudy), and unrequited love (I shyrokuiu dolynu, fragment from the poem Utoplena). The dominance of such a view not only on Shevchenko but also on the whole canon of Ukrainian literature is explicitly hinted at by M. Slavynskyi’s feuilleton for a local newspaper on Shevchenko’s time, where he describes Little Russian literature as literature about peasants and for peasants.19

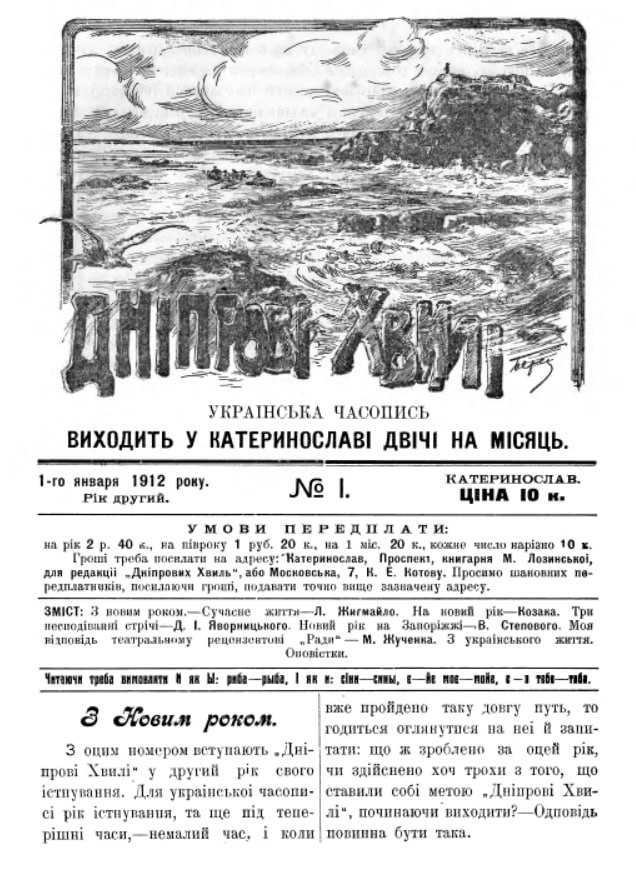

The emergence of Prosvita, the Katerynoslav Literary and Artistic Society, in 1905 was the starting point for the development of a new level of the Shevchenko myth in the structure of the city space. Researchers have already repeatedly noted the significant contribution of Prosvita to honoring Shevchenko.20 The first Ukrainian magazines Dobra Porada (1906) and Dniprovi Khvyli (1910-1913) were published thanks to their efforts. Specific public practices of honoring Shevchenko, such as memorial services, literary and musical evenings, or the reading of popular lectures, are often associated with members of Prosvita.

In modern historiography, Prosvita is considered rather as a hermetic and homogeneous society, which played a leading role in the spread of Ukrainian national consciousness and culture. As a non-governmental organization, but formed with the permission of the current authorities, the local Prosvita alternated periods of fading and revitalization of its activity based on enthusiasm and membership fees. Yet, Prosvita was not the only active public actor that contributed to the memoralization of Shevchenko. Almost simultaneously several scientific and educational institutions directly related to creating the city’s historical discourse appeared, such as the Ekaterinoslav Scientific Archive Commission (1903), the Ekaterinoslav Regional Museum named after Oleksander Pol (1902), and the Ekaterinoslav Scientific Society (1902).

The Archive Commission became a powerful intellectual center for studying local history. Under the patronage of the local leader of the nobility, Prince Nikolay Urusov, who was the nominal head of the body, a cohort of young and active scientists was invited to work in the newly created institution. Among them were sympathizers of the Ukrainian idea, mostly historians D. Yavornytskyi (1855–1940), Vasyl Bidnov (1874–1935), Antyn Sinyavskyi (1866–1951), and D. Doroshenko (1882–1951). All of them were de facto and ideologically members of the local Prosvita.

Three years later, another evening for Shevchenko took place again. In 1905, a solemn meeting of Archive Commission members was held in the premises of the newly built Commercial School, where A. Sinyavskyi was the headmaster. Reports about Shevchenko’s life and work were read, followed by an amateur choir singing Ukrainian folk songs.21 Similar events were held there during 1911–1913.

Press: Looking for “Convenient” Shevchenko

What was Shevchenko like in the public space of Katerynoslav, outside the circle of Ukrainian discourse? The periodical press of different ideological spectrums are revealing. At the beginning of the 20th century, three mass daily newspapers discussing the Shevchenko question on the eve of symbolic anniversaries were published in Katerynoslav—the ideologically neutral newspaper of industrialists Prydneprovskiy Kray,22 the liberal Yuzhnaia Zarya, and the promonarchic Russkaia Pravda. For comparison, it is also important to consider the already mentioned Ukrainian-language magazine Dniprovi Khvyli, which was the in-house publication of the local Prosvita. The Shevchenko issue occupied a significant number of pages. Indeed Shevchenko related items occupied 1/9 of the total number of published materials. Most of them consisted of brief information about the Shevchenko days in the Ukrainian centers both in the Russian Empire and abroad. Every year, the March issue of Dniprovi Khvyli usually had a leading article by the editor-in-chief D. Doroshenko on the occasion of Shevchenko’s anniversary and several reviews of his legacy written by local intellectuals, including Vasyl and Lubov Bidnovy, M. Bykov, M. Novytskyi, and T. Tatarinov.

On the pages of Dniprovi Khvyli, the Shevchenko myth becomes central to constructing the national Ukrainian discourse. Preserving some elements of the narodnytskyi discourse, where the poet suffered with the people and for the people, the accent changes, though, and Shevchenko becomes a “poor genius” and a singer of his homeland.23 In this sense, his uniqueness was determined by self-sacrifice and love for the Motherland. At the same time, Shevchenko’s national myth includes other identity levels that make him more universal. For example, the image of Shevchenko as a humanist, a fighter against serfdom, and a champion of Christian love for humans24 or presenting Shevchenko as a brilliant poet of the Slavic world.

Shevchenko’s representations on the pages of Yuzhnaia Zarya can be considered close to the national discourse. However, in recognizing Shevchenko as the great Kobzar and the prophet of his people, his myth was defined within the supranational community of fraternal Slavic people. Citing the same “spiritual testament” of Shevchenko “I mertvym, i zhyvym…” the authors of Dniprovi Khvyli and Yuzhnaia Zarya come to opposite conclusions. In the text of M. Bykov, Shevchenko appears as a brilliant Ukrainian poet who managed to form a new, unique literature of a separate Ukrainian people.25 Referring to the same fragment of the poem in the liberal Yuzhnaia Zarya, the author suggests honoring Shevchenko as a symbol of fraternal unity in times of exciting nationalism.26 Moreover, the polysemantic quote: “Obiimit zhe, braty moi, naimenshoho brata” in the same issue will be used as a reason to recall Shevchenko’s idea of Christian love for all suffering in order to overcome hunger in the Russian provinces.27

The difference between the two visions of Shevchenko is dictated not only on the level of rhetoric and symbols but also as the difference between a magazine, addressed to a narrow circle of intellectuals and peasants, and a daily city newspaper, concentrated not so much on ideological views as on consumer needs. To be commercially attractive, a socio-political newspaper had to respond to the most sensational news from various segments of public life. That is why the editors of Yuzhnya Zarya showed a keen interest in Shevchenko’s days in the anniversaries of 1911 and 1914, dedicating entire issues to Shevchenko. Their search for exclusive material sometimes takes unexpected forms. Thus during 3 issues, the newspaper covered the details of a public scandal that happened at the evening feast after the Shevchenko party in the hall of the Commercial Assembly in 1912. Yet, when the issue had less public resonance, the editorial office limited itself to reminders of celebrations on annual days or published chronicles of such events. Differences in semantic horizons can also be traced in explaining Shevchenko’s uniqueness. In the case of Dniprovi Khvyli, oriented toward peasants and workers, the myth of Shevchenko is described as an imaginary center for narrower categories (such as the Ukrainian language, literature, or popular will). Simply put, the question “Which hero is Shevchenko an analog for?” did not occur—except that in the leading article D. Doroshenko referred to the analogy of Shevchenko with Polish national hero A. Mickiewicz.28 On the other hand, the search for analogies in other cultures (primarily Russian), through which the national phenomenon of Shevchenko could be understood was much more common in Yuzhnya Zarya. According to K. Ivanov, a member of the State Duma, Shevchenko’s lyre in the people’s cause stood much higher than the work of Koltsov and Nikitin, and he defined the goal of Kobzar’s work with S. Pushkin’s call: “To burn the hearts of people by the verbs… Seeking truth.” ((Yvanov K. Po povodu chestvovanyia pamiaty T. Shevchenko [On the occasion of honoring the memory of T. Shevchenko]. Yuzhnaia zaria, № 2302 (26 February 1914): 2.)) In the next issue, M. Bykov compared the fate of Shevchenko with Shakespeare’s character, and considered his importance for the Ukrainian people comparable to the importance of L. Tolstoy and F. Dostoevsky for Russians.29

The editors of the pro-anarchist Russkaia Pravda took a more critical position on the national myth of Shevchenko. As K. Fedevych convincingly shows, until the 1910s Ukrainian and even Russian monarchists actively used the myth of Shevchenko for their own political purposes, contrary to the widespread opinion about the antagonism between imperial monarchism and Shevchenko’s work.30

Along with the recognition of Kobzar’s talent, extraordinary fate, and importance as a great Ukrainian or Little Russian poet, there were attempts to desacralize Shevchenko as an exceptional national hero. Similar to Yuzhnaia Zarya, the accent was placed on the worldview of the poet himself, in other words on his Slavophile ideas. The final result of such a vision was subordinated to other ideological tasks, including constructing the image of an external enemy. The situational quoting of the same message (“I mertvym, i zhyvym…”) was instrumentalized in highlighting the negative side of the expansion of German capital on the locus of the Ukrainian Cossacks—Khortytsia Island.31

In his memoirs, D. Doroshenko mentions that the ideological tension between supporters of the Ukrainian movement and monarchists in Katerynoslav was not as antagonistic as in Kyiv.32 The dynamics and forms of Shevchenko’s discourse in Russkaia Pravda reflect similar things. As early as 1911, the editorial office would not only reprint some materials from Dniprovi Khvyli in Ukrainian (!) or inform readers about the memorial service and Shevchenko’s readings in the Archive Commission, but even advertise (!) the Ukrainian magazine itself.33

The general tension in the empire and the appropriation of the Shevchenko myth by various political forces reached a critical point on the eve of the celebration of the poet’s anniversary in 1914. The catalyzing factor was the strange decision of N. Maklakov, the Minister of Internal Affairs, to ban any celebrations on the occasion of Shevchenko’s 100th birthday on the empire territory a month before the event. This measure, in his opinion, was supposed to prevent turning the anniversary into a political manifestation. However, rather than preventing politicization, the ban politicized the issue, since previously such celebrations were shaped more by tradition than by political choice. The ban highlighted governmental control over cultural and historical expressions.

This shift is reflected by the change of rhetoric regarding Shevchenko’s reception in Russkaia Pravda around the time of his anniversary. If earlier it was permissible to refer to Shevchenko as a great Ukrainian poet, after 1914 he was demonstratively turned into a Little Russian figure. Initially, the Ukrainian component of the Shevchenko myth is gradually eroded through the discourse of Slavic unity and the fight against serfdom. Then the national component was criticized, due to the focus on Shevchenko’s Polophobic and Judeophobic statements.34 The attitude of pro-monarchic forces toward Shevchenko was ambivalent. On the one hand, there was a recognition of the need to honor Kobzar due to his significant contributions to the development of Ukrainian (Little Russian) culture. On the other hand, official discourse framed the public honoring of Shevchenko as potentially subversive, turning it into a matter of political protest.

In the case of Katerynoslav, where the celebrations took place with the approval and participation of the local authorities, the right-wing Russkaia Pravda’s position did not find much support. The editors reported that they received about 200 letters with accusations of distorting the truth about Kobzar and looking for politics where there was none.35 The rhetoric of Russkaia Pravda in the context of the city’s events really looked strange—while the traditional Shevchenko events were taking place, the editors covered the “horrors” of radical students in Kyiv who sang: “Da zdravstvuet samostiina Ukraina!” [Long live to independent Ukraine].36

City and Centenary Anniversary

The initiative to hold Shevchenko’s centenary of birth in 1914 came from the members of the Council of Katerynoslavska Prosvita at the end of 1913. In December, the governor granted permission to assemble a separate Anniversary Committee, supplemented by members of other institutions and societies. At the very first meeting, the committee decided to invite for cooperation members of the State Duma from the Katerynoslav province, all members of the city and Zemstvo administrations, higher and secondary schools, various associations, and institutions. As a result, about 300 telegrams were sent to private individuals and 27 letters to organizations.37 The anniversary Committee counted on financial support from the city authorities.

At the beginning of January 1914, residents submitted an application to the City Duma, requesting a response to the anniversary of Shevchenko. The signatories emphasized the cultural duty of Katerynoslav to the population of the region, which speaks in the language of Kobzar, and appealed to the historical significance of their region in the destiny of the Ukrainian people. Here, the regional consciousness was interpreted as a part of the national one—although people expected Kyiv to be the centre of the anniversary celebrations.38

The application to the Duna was signed by 747 people, but did not contain specific proposals, only emphasizing the need to support the celebration. Later, however, the Committee adopted an appendix with specific recommendations that should be implemented. Among them were setting up a monument to the poet in Katerynoslav, establishing a named scholarship in higher schools, distributing portraits, busts, and editions of Kobzar among students, naming one of the city streets after Shevchenko, and opening a department of Ukrainian literature in the city library. Later, the Committee submitted a request for financing the anniversary in the amount of 500 rubles. A similar proposal was also sent to the Katerynoslavske Zemstvo, but the real financial support came only from the City Duma.39

There were also proposals that the Committee decided not to send to the Duma. One of them was expressed by D. Yavornytskyi, who proposed to publish Shevchenko’s biography materials from the local museum at the city’s expense.40 Another, expressed by the local doctor Yakiv Neishtab, proposed to establish an educational institution named after Shevchenko with a Ukrainian theater and library under a motto: “Not to pursue any political aspirations that would conflict with common national goals.” ((Zvidomlennia pro diialnist Yuvileinoho shevchenkovoho komitetu…))

The main tasks of the Committee were the preparation of the celebration program and coordination of interested agents. It was planned to hold a solemn meeting on February 25 in the hall of the prestigious English Club and a memorial service for Shevchenko on the evening of February 26. The program for the evening consisted of an introduction by O. Terpygorev, the chairman of the Committee, a speech entitled Shevchenko is a Peopl’s Poet by D. Yavornytskyi, a professor of the Katerynoslav Mining Institute, and the report The Great Poet of People’s Humanity by M. Bykov’s. The speeches were subsequently published in the Yuzhnaia Zarya and seemed to be reworked versions of articles published 2 years earlier in the works of the Archival Commission.41

The second part of the program consisted of the ceremony of laying wreaths and greeting cards at the bust of the poet, choral singing, and recitations of Shevchenko’s works, which were allowed by the censorship—Chernets and Do Osnovianenka. The text of the greeting cards was published in the press and in the committee’s report, enabling us to compare Shevchenko’s reception by different groups and societies.

Many postcards were addressed to the poet from Prosvita branches in the surrounding villages. All of them refer to the poet as a symbolic father, apostle of truth, and prophet of a better destiny. However, peasants perceived “their own” Shevchenko in the social sense, often identifying him through the national discourse. For example, they could address Shevchenko as a singer of people’s grief or Ukraine’s misfortunes; as peasant’s Father Taras or the glorious Father of Ukraine. All such letters are written in Ukrainian.

The technical intelligentsia and members of the local Scientific Society spoke to a completely different Shevchenko. Recognizing him as a great poet or even a genius Kobzar of Ukraine, they looked at him through the myth of a humanist writer and singer of civic ideals. In their postcards, they repeatedly call him a folk poet or a founder of Ukrainian folk poetry, yet never identify him as their own hero. A similar perception of Shevchenko is present in telegrams from the authorities, which noted his poetic talent for reflecting the people’s life and spirit.42 Most of the postcards from this group of actors are written in Russian.

Such alternative discourses of Shevchenko’s legacy prompted Prosvita and the Scientific Society to organize alternative educational events. Both institutions treated Shevchenko mostly as an ideological tool. One of F. Matushevsky’s interlocutors during a short visit to Katerynoslav complained about the local Prosvita, which used Shevchenko’s name to get more money for Ukrainian parties.43 In turn, the Scientific Society arranged readings in suburban public auditoriums in 1911, timed to combine the 50th anniversary of the abolition of serfdom with Shevchenko’s days on February 26. The success of such lectures was enormous, as they gathered from 400 to 600 listeners.44

Conclusions

The myth of Shevchenko, as part of the Ukrainian national discourse, had a non-linear development in Katerynoslav. As it emerged in the public sphere in the mid-1880s, the narodnytskyi myth of Shevchenko circulated mainly in a narrow milieu of intelligentsia, interested in local folklore and ethnography. In honoring Shevchenko, they respected first of all the object of their ardent interest—the people by which they understood the traditional world of the Ukrainian peasantry. Yet, the weak development of public infrastructure and the dominance of local and imperial identities in the urban environment made Shevchenko’s peasant myth alien to the city.

The situation changed at the beginning of the 20th century when a network of educational institutions and public associations that connected their activities to Ukrainian history and affairs emerged in the city. In Katerynoslav, the tradition of the annual commemoration of the anniversary of Shevchenko’s death was formed largely as a result of the arrival of intellectuals from more developed Ukrainian centers—Kyiv and St. Petersburg. Not least thanks to their efforts, new public actors and organizations were formed. One of them was Prosvita, which put Shevchenko at the center of its activities.

Guided by personal sympathy for Shevchenko’s heritage or loyalty to Ukrainian affairs, Prosvita tried to expand the Ukrainian discourse by using the resources of the official institutions in which their representatives worked. A whole network of institutions that used Shevchenko’s myth was formed, including the Ekaterinoslav Archeographic Commission, Ekaterinoslavska Prosvita, and the Historical Museum named after O. Pol. The cooperation between these institutions and their interaction with the authorities depended largely on personal relationships. The jubilee celebrations in 1914 quite possibly could not have taken place if D. Yavornytsky had not used his authority and good relations with the local politicians to convince them to allow “apolitical” celebrations.

As T. Portnova points out, the “active” bearers of the Ukrainian idea, first of all, were the representatives of urban intelligentsia, who at the same time had to maintain loyalty to the ruling discourse and caution in expressing their own views.45 Therefore, all Shevchenko celebrations took place only with the approval of local authorities. Such optics allow us to look at the interaction of public and private spheres not only as conflicting but also from the standpoint of interaction and social agreement.

The activities of this group of public agents led to the expansion of the Shevchenko discourse which could no longer be ignored by actors not related to the Ukrainian idea. The incorporation of the national myth of Shevchenko as a liberator of peasants and people’s prophet into the urban space sparked an interest among liberals and rightists in adapting Shevchenko’s image to align with their ideological perspectives. This strategy leveraged the high awareness among urban residents who originated from rural areas—while they might not have been familiar with Taras Shevchenko, they were likely already acquainted with the idea of Kobzar.46

Meanwhile, the place of Shevchenko’s discourse in the system of the urban public sphere should not be overestimated. It had a high potential for adaptation as a symbol of the Ukrainian national identity in the urban population segment. Such tendency should be perceived not as part of the teleological process of nationalization of the city, but as a dynamic process of searching for its own face and identity.

List of Sources

Newspaper articles:

- Bykov M. Tarasova slava [Taras’ glory]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 133–134.

- Bykov N. Velykyi poet narodnoi chelovechnosty [Great poet of the people’s humanity]. Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 2305 (28 February 1914): 2–3.

- Chestvovanye Shevchenko [Honoring Shevchenko]. Russkaia Pravda, № 2132 (28 February 1914): 1.

- H.S. Shevchenko y evrey [Shevchenko and jews]. Russkaia Pravda, № 2130 (26 February 1914): 2.

- Iavornytskyi D. T.H. Shevchenko – narodnyi ukrainskyi poet [T.H. Shevchenko is Ukrainian folk poet]. Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 2306 (1 March 1914): 2

- Katerynoslavska presa pro Shevchenka [Katerynoslav press about Shevchenko]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 138–139.

- K yubyleiu Shevchenko [For Shevchenko’s anniversary]. Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 2277 (26 January 1914): 2.

- Matushevskyi F. Lysty z dorohy [Travel letters]. Rada, № 195 (29 August 1909): 2–3.

- Matushevskyi F. Lysty z dorohy[Travel letters]. Rada, № 201 (3 September 1909): 2–3.

- Novytskyi N. Shevchenkovskyi yubyleinyi komytet [Shevchenko Jubilee Committee]. Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 2279 (29 Junuary 1914): 2.

- Pamiati L. Sokhachevskoi [In memory of L. Sokhachevska]. Russkaia Pravda, № 1341 (16 Junuary 1911): 2.

- Russkaia Pravda, № 1253 (26 February1911).

- Russkaia Pravda, № 1767 (27 November 1912).

- Yvanov K. Po povodu chestvovanyia pamiaty T. Shevchenko [On the occasion of honoring the memory of T. Shevchenko]. Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 2302 (26 February 1914): 2.

- Yubyleinye demonstratsyy [Demonstrations at the anniversary]. Russkaia Pravda, № 2131 (27 February 1914): 3.

- Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 1716 (25 February 1912).

- Yuzhnaia Zaria, № 1724 (5 March 1912).

- Zhuchenko M. (Doroshenko D.) Velyki rokovyny [Great anniversary]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 129–131.

- Zhyhmailo L. (Bidnova L.) Do Shevchenkovoho yuvileiu [To Shevchenko’s anniversary]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 132–133.

Secondary sources:

- Chaban M. (2001) U staromu Katerynoslavi (1905–1920 rr.). Khrestomatiia. Misto na Dnipri ochyma ukrainskykh pysmennykiv, publitsystiv i hromadskykh diiachiv. Dnipropetrovsk.

- Doroshenko D. (2007) Moi spomyny pro davnie mynule (1901–1914 roky). Kyiv: Tempora.

- Kyevskaia staryna, Vol. 77 (April 1902). [Digital copy]: https://elib.nlu.org.ua/object.html?id=8237

- Zvidomlennia pro diialnist Yuvileinoho shevchenkovoho komitetu v Katerynoslavi (1915). Katerynoslav.

Bibliography

- Bojanowska E. (2013). Nikolai Gogol. Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Kyiv: Tempora. [Ukraine translation].

- Calhoun K. (2006) Nationalism. Moscow: Terrytoryia buduiushcheho. [Russian translation].

- Drahomanov M. (1991) Shevchenko, ukrainofily i sotsializm. Kyiv: Lybid.

- Fedevych K. I., Fedevych K. (2017) K. Za Viru, Tsaria i Kobzaria. Malorosiiski monarkhisty i ukrainskyi natsionalnyi rukh (1905 – 1917). Kyiv: Krytyka.

- Grabowicz G. (1998) The Poet as Mythmaker. A Study of Simbolic Meaning in Taras Ševčenko. Kyiv: Krytyka. [Ukraine translation].

- Holyk R. (2014) Shevchenkova tvorchist: chytannia ta suspilno-ideolohichni uiavlennia v Halychyni ХІХ –ХХ st. Ukrainian Historical Journal, 3, 100–115.

- Kasianov G. (1999) Teorii natsii ta natsionalizmu. Kyiv: Lybid.

- Letopys Ekaterynoslavskoi uchenoi arkhyvnoi komyssyy (1904 – 1915). Biohrafichnyi dovidnyk. (1991) / Coml. by C. Ambrosymova, O. Zhurba, M. Kravets. Kyiv.

- Lysenko O. (2010) Prosvitianskyi rukh Naddniprianshchyny v 1905–1919 rokakh. Ukraina: kulturna spadshchyna, natsionalna svidomist, derzhavnist: Zbirnyk naukovykh prats, 19, 516–521.

- Marholys Y. (1983) T.H. Shevchenko y Peterburhskyi unyversytet. Leningrad.

- Myronov B. (2012) Blahosostoianye naselenyia y revoliutsyy v ymperskoi Rossyy: XVIII –nachalo XX v. Moscow: Ves myr.

- Pamiati Shevchenka. Istoryko-literaturnyi zbirnyk. 1814 – 1939. (1939) / Ed. By I. Hrushytskiy. Dnepropetrovsk.

- Portnova T. (2016) Liubyty i navchaty: selianstvo v uiavlenniakh ukrainskoi intelihentsii druhoi polovyny ХІХ stolittia. Dnepropetrovsk: Lira.

- Portnova T. (2008) Miske seredovyshche i modernizatsiia: Katerynoslav seredyny ХІХ – pochatku ХХ st. Dnipropetrovsk.

- Sereda O. (2013) Pershi publichni deklamatsii poezii Tarasa Shevchenka ta shevchenkivski “vechernytsi” u Halychyni. Ukraina: kulturna spadshchyna, natsionalna svidomist, derzhavnist, 23, 18–33.

- Shevchenkiana Prydniprovia. Statti, narysy, poeziia, esei, interviu. (2008) / Coml. by L. Stepovychka and M. Chaban. Dnipropetrovsk.

- Silvanovych S. (2021) Formuvannia miskoho panteonu Katerynoslava u druhii polovyni ХІХ– na pochatku ХХ st. (za materialamy periodychnykh dovidkovo-statystychnykh vydan). // U poshukakh oblychchia mista: praktyky samoreprezentatsii mist Ukrainy v industrialnu ta postindustrialnu dobu. Kharkiv, 312–329.

- Svitlenko S. (2006) Suspilnyi rukh na Katerynoslavshchyni u 50–80-kh rokakh ХІХ st. Dnipropetrovsk: Lira.

- Svitlenko S. (2019) Uvichnennia pamiati Tarasa Shevchenka v ukrainskomu natsionalnomu rusi Naddniprianshchyny na pochatku ХХ st. Hrani, 24(3), 71–79.

- Svitlenko S. (2018) Ukrainske XIX stolittia: etnonatsionalni, intelektualni ta istoriosofski konteksty. Dnipro: Lira.

- The Invention of Tradition. (2015) / Ed. by E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger. Kyiv: Nika-Center. [Ukraine translation].

- Utesheva H. (2009) Do istorii lektsiinoi roboty Katerynoslavskoho naukovoho tovarystva na pochatku XX st. // Istoriia i kultura Prydniprovia http://politics.ellib.org.ua/pages-cat-100.html

- Vasylenko N. Yehorov Oleksandr Ivanovych (1850-1903). https://www.libr.dp.ua/region-egorov.html

- Voronov V. (2017) Shevchenkiana na storinkakh chasopysu «Kyevskaia staryna». Naddniprianska Ukraina: istorychni protsesy, podii, postati, 15, 40–57.

- Yekelchyk S. (2005) Tvorennia sviatyni: ukrainofily ta shevchenkova mohyla v Kanevi (1861 – 1900 rr.). Zbirnyk Kharkivskoho istoryko-filolohichnoho tovarystva, Vol. 11, 43–58.

- Zabuzhko O. (2017) Shevchenkiv mif Ukrainy. Sproba filosofskoho analizu. Kyiv: Komora.

- Zhurba O. (2016) Istorychna kultura Katerynoslavshchyny ta osoblyvosti formuvannia istorychnoi pamiati rehionu. Kharkivskyi istoriohrafichnyi zbirnyk, 15, 163–173.

- Grabowicz G. The Poet as Mythmaker. A Study of Symbolic Meaning in Taras Ševčenko; Zabuzhko O. Shevchenkiv mif Ukrainy. Sproba filosofskoho analizu. [↩]

- Drahomanov M. Shevchenko, ukrainofily i sotsializm. [↩]

- Yekelchyk S. Tvorennia sviatyni: ukrainofily ta shevchenkova mohyla v Kanevi (1861 – 1900). Zbirnyk Kharkivskoho istoryko-filolohichnoho tovarystva, Vol. 11, 43–58; Holyk R. Shevchenkova tvorchist: chytannia ta suspilno-ideolohichni uiavlennia v Halychyni ХІХ –ХХ st. Ukrainian Historical Journal, 3, 100–115. [↩]

- The Invention of Tradition. / Ed. by E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger. P. 13–14 [↩]

- Zabuzhko O. Shevchenkiv mif Ukrainy… P. 44. [↩]

- Bojanowska E. Nikolai Gogol. Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. P. 25; Calhoun K. Nationalism. P. 12-13. [↩]

- Kasianov G. Teorii natsii ta natsionalizmu. P. 151. [↩]

- Portnova T. Miske seredovyshche i modernizatsiia: Katerynoslav seredyny ХІХ – pochatku ХХ st.; Myronov B. Blahosostoianye naselenyia y revoliutsyy v ymperskoi Rossyy: XVIII – nachalo XX v. [↩]

- Zhurba O. Istorychna kultura Katerynoslavshchyny ta osoblyvosti formuvannia istorychnoi pamiati rehionu. Kharkivskyi istoriohrafichnyi zbirnyk, 15, 163–173. [↩]

- Yekelchyk S. Tvorennia sviatyni: ukrainofily ta shevchenkova mohyla v Kanevi (1861 – 1900). P. 44. [↩]

- Voronov V. Shevchenkiana na storinkakh chasopysu “Kyevskaia staryna.” Naddniprianska Ukraina: istorychni protsesy, podii, postati, 15, 40–57. [↩]

- Marholys Y. T.H. Shevchenko y Peterburhskyi unyversytet; Sereda O. Pershi publichni deklamatsii poezii Tarasa Shevchenka ta shevchenkivski “vechernytsi” u Halychyni. Ukraina: kulturna spadshchyna, natsionalna svidomist, derzhavnist, 23, 18–33. [↩]

- Pamiati Shevchenka. Istoryko-literaturnyi zbirnyk. 1814 – 1939 / Ed. By I. Hrushytskiy. [↩]

- Vasylenko N. Litopys literaturno-mystetskykh podii ta sviat pamiati Tarasa Shevchenka v Katerynoslavi // Shevchenkiana Prydniprovia… P. 127. [↩]

- Svitlenko S. Suspilnyi rukh na Katerynoslavshchyni u 50–80-kh rokakh ХІХ st. P. 92. [↩]

- Silvanovych S. Formuvannia miskoho panteonu Katerynoslava u druhii polovyni ХІХ– na pochatku ХХ st. (za materialamy periodychnykh dovidkovo-statystychnykh vydan). // U poshukakh oblychchia mista: praktyky samoreprezentatsii mist Ukrainy v industrialnu ta postindustrialnu dobu. 312–329. [↩]

- Portnova T. Miske seredovyshche i modernizatsiia… [↩]

- Dokumenty, yzvestyia, zametky // Kyevskaia staryna, Vol. 77 (April 1902). P. 30–31. [↩]

- Dokumenty, yzvestyia, zametky // Kyevskaia staryna, Vol. 77 (April 1902). P. 28. [↩]

- Lysenko O. Prosvitianskyi rukh Naddniprianshchyny v 1905–1919 rokakh. Ukraina: kulturna spadshchyna, natsionalna svidomist, derzhavnist: Zbirnyk naukovykh prats, 19, 516–521. [↩]

- Fomenko A. T.H. Shevchenko i Katerynoslavska “Prosvita” // Shevchenkiana Prydniprovia… P. 85–90. [↩]

- The publication is currently not available for research. The presence of passive discourse and reaction on the eve of the Shevchenko anniversary is noted by the editor of Dniprovi Khvyli. Look: Katerynoslavska presa pro Shevchenka [Katerynoslav press about Shevchenko]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 138–139. [↩]

- Zhuchenko M. (Doroshenko D.) Velyki rokovyny [Great anniversary]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 129–131. [↩]

- Zhyhmailo L. (Bidnova L.) Do Shevchenkovoho yuvileiu [To Shevchenko’s anniversary]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 132–133. [↩]

- Bykov M. Tarasova slava [Taras’ glory]. Dniprovi Khvyli, № 10 (2 March 1911): 133–134. [↩]

- Po povodu sehodniashnei hodovshchyny [About today’s anniversary]. Yuzhnaia zaria, № 1716 (25 February 1912): 3. [↩]

- Zabytye slova [Forgotten words]. Yuzhnaia zaria, № 1716 (25 February 1912): 3. [↩]

- Zhuchenko M. (Doroshenko D.) Velyki rokovyny… P. 130. [↩]

- Bykov N. Velykyi poet narodnoi chelovechnosty [Great poet of the people’s humanity]. Yuzhnaia zaria, № 2305 (28 February 1914): 2–3. [↩]

- Fedevych K. I., Fedevych K. K. Za Viru, Tsaria i Kobzaria. Malorosiiski monarkhisty i ukrainskyi natsionalnyi rukh (1905 – 1917). [↩]

- Russkaia pravda, № 1767 (27 November 1912): 3. [↩]

- Doroshenko D. Moi spomyny pro davnie mynule (1901–1914 roky). P. 169. [↩]

- Russkaia pravda, № 1253 (26 February 1911): 3. [↩]

- H.S. Shevchenko y every [Shevchenko and jews]. Russkaia pravda, № 2130 (26 February 1914): 2. [↩]

- Chestvovanye Shevchenko [Honoring Shevchenko]. Russkaia pravda, № 2132 (28 February 1914): 1. [↩]

- Yubyleinye demonstratsyy [Demonstrations at the anniversary]. Russkaia pravda, № 2131 (27 February 1914): 3. [↩]

- Novytskyi N. Shevchenkovskyi yubyleinyi komytet [Shevchenko Jubilee Committee]. Yuzhnaia zaria, № 2279 (29 Junuary 1914): 2. [↩]

- K yubyleiu Shevchenko [For Shevchenko’s anniversary]. Yuzhnaia zaria, № 2277 (26 January 1914): 2. [↩]

- Zvidomlennia pro diialnist Yuvileinoho shevchenkovoho komitetu v Katerynoslavi. [↩]

- Which were already partially published by him several years ago: Yavornytskyi D. (1909) Materialy do biohrafii T.H. Shevchenko. Katerynoslav. [↩]

- Bykov N. Narodnaia dusha v tvorenyiakh T.H. Shevchenko; Evarnytskyi D. Zaporozhtsy v poezyy T.H. Shevchenko // Letopys Ekaterynoslavskoi uchenoi arkhyvnoi komyssyy (1904 – 1915). Biohrafichnyi dovidnyk. (1991) / Coml. by Ambrosymova C., Zhurba O., Kravets M. P. 8–20. [↩]

- Zvidomlennia pro diialnist Yuvileinoho shevchenkovoho komitetu… [↩]

- Matushevskyi F. Lysty z dorohy [Travel letters]. Rada, № 201 (3 September 1909). P. 2. [↩]

- Utesheva H. Do istorii lektsiinoi roboty Katerynoslavskoho naukovoho tovarystva na pochatku XX st. Istoriia i kultura Prydniprovia. [↩]

- Portnova T. Liubyty i navchaty: selianstvo v uiavlenniakh ukrainskoi intelihentsii druhoi polovyny ХІХ stolittia. [↩]

- Matushevskyi F. Lysty z dorohy [Travel letters]. Rada, № 195 (29 August 1909). P. 3. [↩]